The Sun Between the Storms; Part II, Berlin

An Odyssey of the 1920’s: Berlin in the Weimar Republic.

When the Armistice took effect at 11:00 am GMT on November 11, 1918, it brought an effective end to what would become known as the First World War: four years of bitter conflict that not only took the lives of over 9 million young soldiers but also spawned widespread famine and disease in the civilian populations of Europe. The political, cultural, and social order on the continent was drastically changed. New countries were formed, old ones abolished, and along with these changes ideologies both new and old found fertile ground.

In 1919 a national assembly convened in Weimar, (Thuringia) Germany to establish a new constitution for the German Reich. Adopted in August of that same year, the new Weimar Republic was immediately faced with numerous problems; hyperinflation, political extremists and paramilitaries on both the left and right. Yet the ensuing period of liberal democracy proved a great draw for intellectuals, artists, and innovators from many fields; the brief reign of the Weimar Republic is frequently cited as having one of the highest levels of intellectual production in human history.

The history of the Weimar Republic from 1919 to 1933 illuminates one of the most creative and crucial periods in the twentieth century. Despite its flaws, it was was a genuine attempt to create the perfect democratic country.

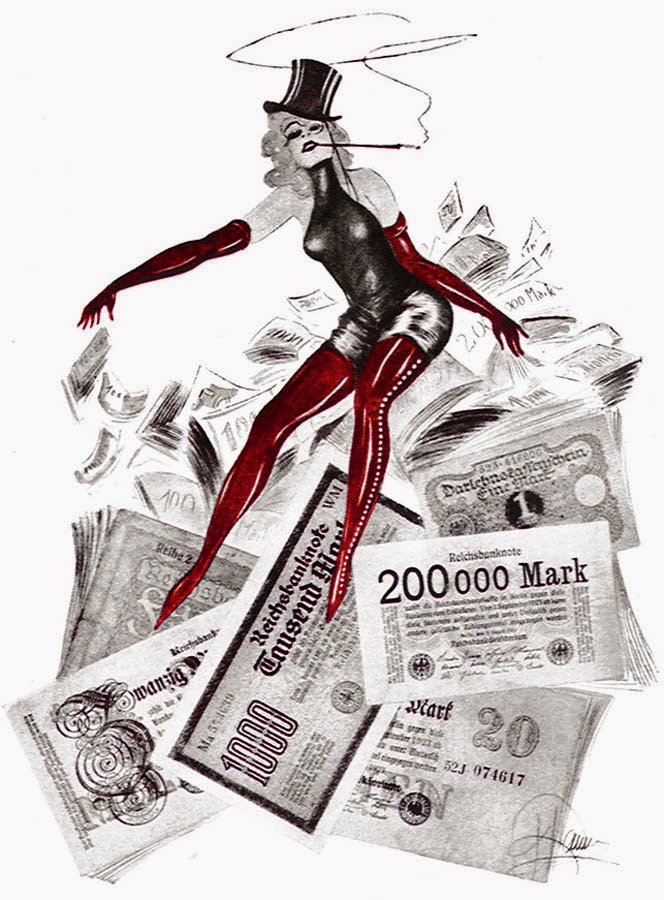

Germany in the 1920’s possessed some the most world’s most advanced science and technology. By the end of the war Berlin rose as the hectic center of the Weimar culture, already swelling with an influx of refugees fleeing both economic and physical hardships, turning it into one of the most fertile grounds for the modern arts and sciences in history. People began using their backyards and basements to run small shops, restaurants and workshops; this led to the overall establishment of better commerce, despite the looming specter of hyperinflation. In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

During the worst phase of hyperinflation in 1923, the clubs and bars were full of speculators eager to spend their daily profits before they lost value by the next morning.

|

| Josephine Baker |

Intellectuals responded by condemning the excesses and demanding revolutionary changes; under influence of the brief cultural explosion in the Soviet Union German literature, cinema, theatre and musical works entered a phase of great creativity. Innovative street theatre brought plays to the public, and the cabaret scene and jazz bands became very popular. Young women were quickly “Americanised”, breaking with traditional mores. The euphoria surrounding Josephine Baker in the metropolis of Berlin for instance, where she was declared an “erotic goddess” and in many ways admired and respected, kindled further “ultramodern” sensations in the minds of the German public.

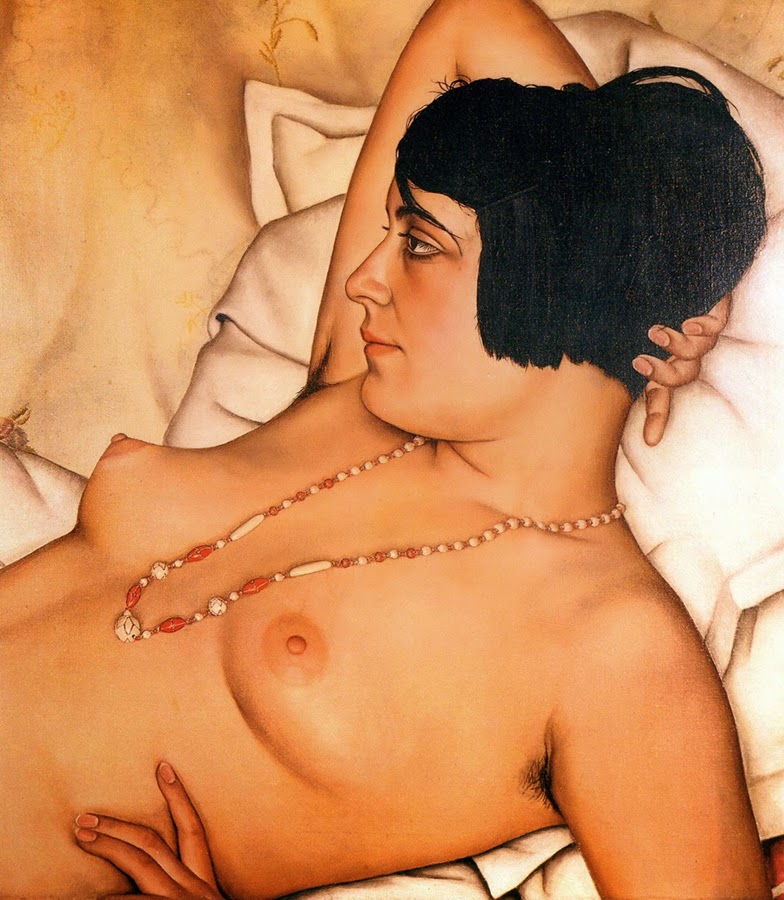

The Weimar Republic was born into the midst of several major movements in the fine arts. German Expressionism had begun before World War I, and continued to have a strong influence throughout the 1920s although artists often positioned themselves in opposition to expressionist styles as the decade went on.

Dada had also begun in Zurich during World War I, and as it became an international phenomenon Richard Huelsenbeck established the Berlin group, whose members included Jean Arp, John Heartfield, Wieland Hertzfelde, Johannes Baader, Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz and Hannah Höch. Machines, technology, and a strong Cubism element were features of their work. Jean Arp and Max Ernst formed a Cologne Dada group, and held a Dada Exhibition there that included a work by Ernst that had an axe “placed there for the convenience of anyone who wanted to attack the work”.

|

| First International Dada Fair in Berlin, 1920 |

|

| Reconstruction of the Merzbau, Sprengel Museum |

Kurt Schwitters established his own one-man Dada “group” in Hanover, where he filled two stories of a house (the Merzbau) with sculptures cobbled together from found objects and ephemera, each room dedicated to a different artist friend of Schwitter’s. The house was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1943, but the Sprengel Museum holds a reconstruction of the Merzbau’s main room, made in 1981–83 by Peter Bissegger.

|

| “Afternoon“, Max Beckman |

|

| “Family Picture“, Max Beckmann |

|

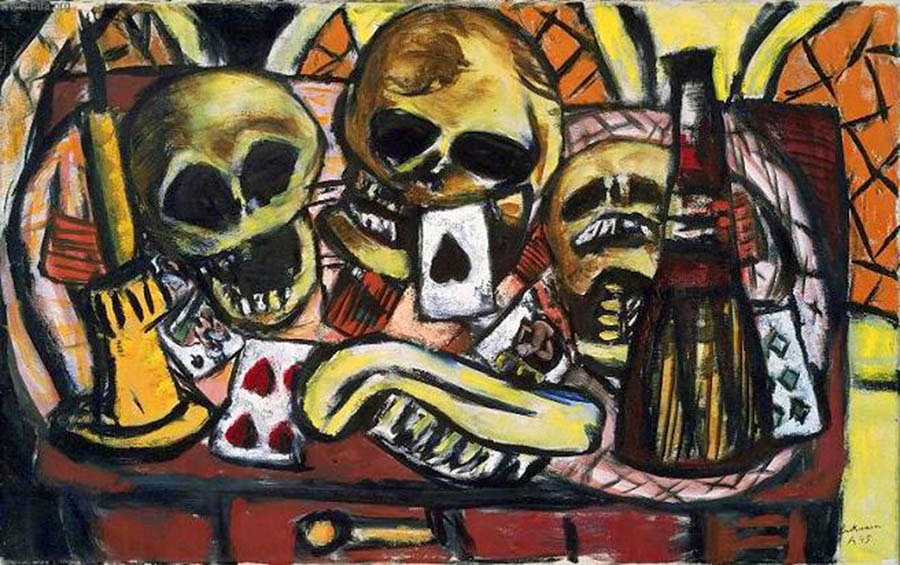

| “Still Life With Skulls“, Max Beckmann |

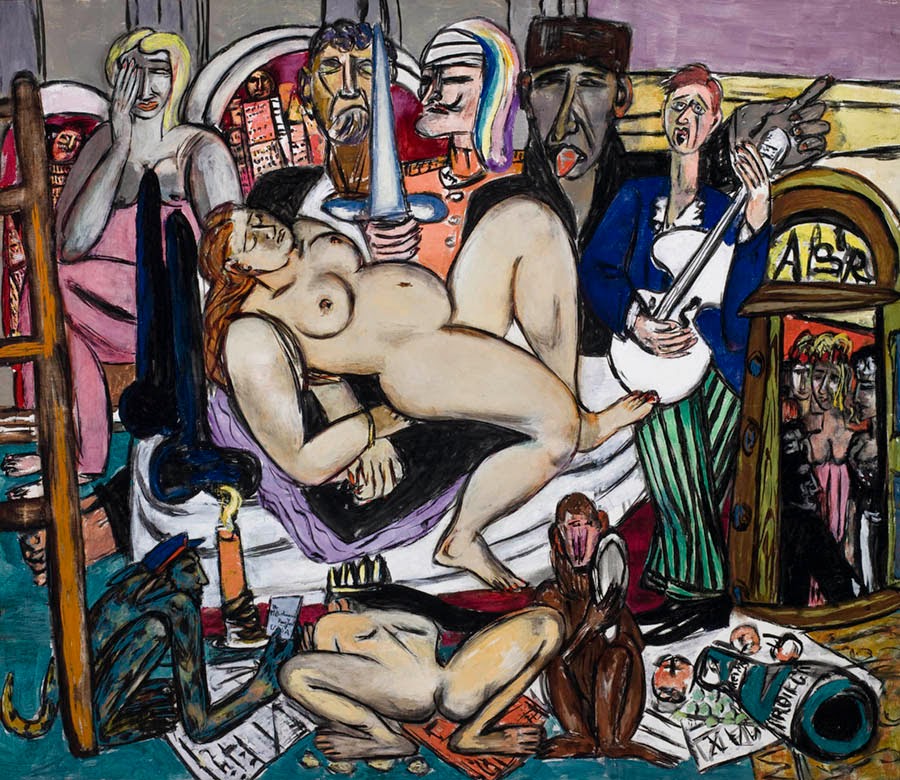

The New Objectivity artists did not belong to a formal group, but various Berlin artists were oriented towards the concepts associated with it. Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Conrad Felixmüller, Christian Schad, and Rudolf Schlichter all worked in different styles, but shared many of the same themes: the horrors of war, social hypocrisy and moral decadence, the plight of the poor and the rise of Nazism.

|

| George Grosz “Explosion“ |

|

| George Grosz “Metropolis“ |

Otto Dix and George Grosz referred to their own movement as Verism, a reference to the Roman classical approach called verus, meaning “truth”- warts and all. While their art is recognizable as a bitter, cynical criticism of life in the new republic, they were striving to portray a sense of realism that they saw missing from expressionist works. New Objectivity became a major undercurrent in all of the arts during the Weimar Republic.

|

| “Circus Artists“, August Sander |

|

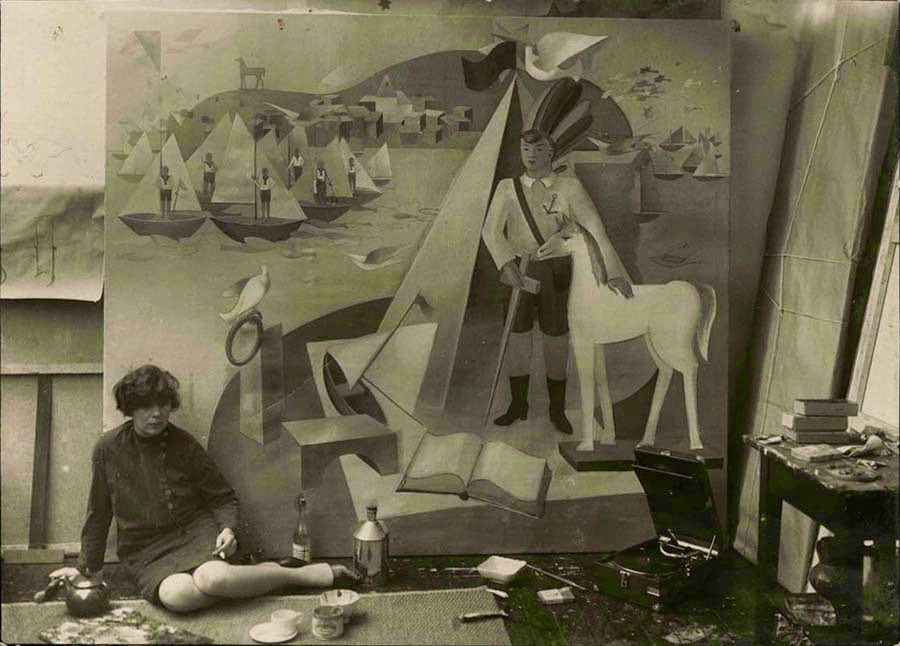

| “Marta Hegemann“, August Sander |

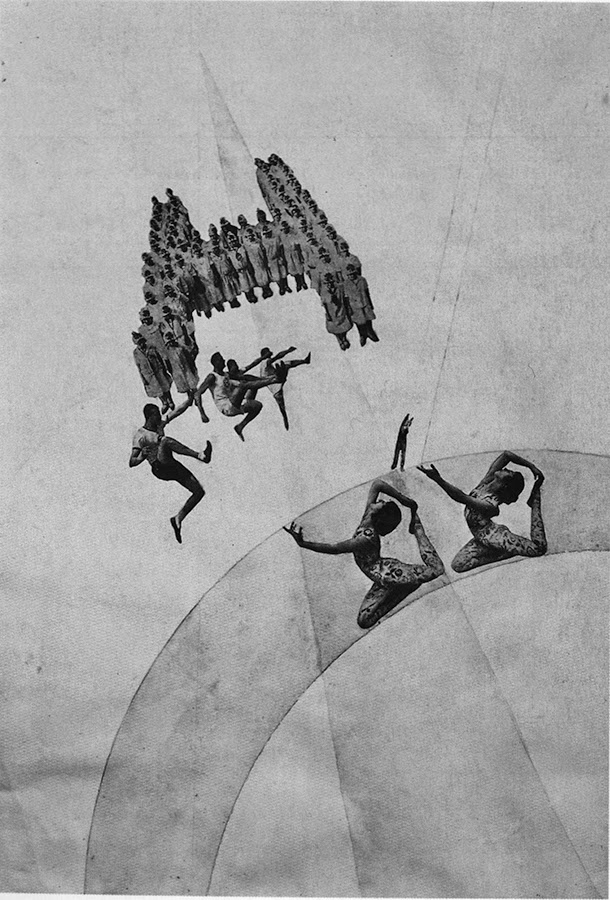

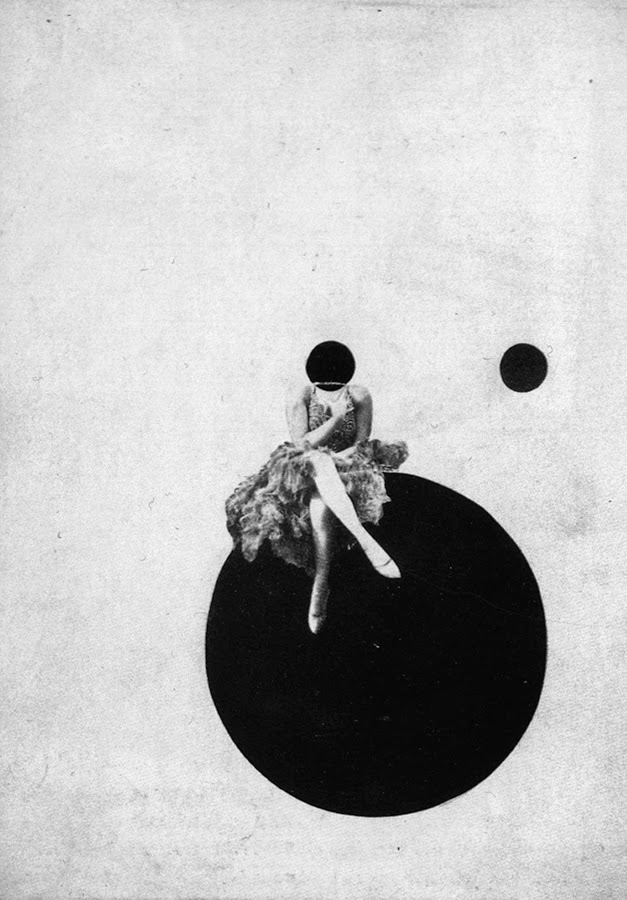

A rapid development of photography, both as a medium of creative expression and as a vehicle of social consciousness, began in the decade immediately following the Great War. Avant-garde artists, commercial illustrators and journalists turned to photography as if seeking to discover the soul of contemporary industrial society.

The camera’s ability to mirror the face of society was by no means abandoned, but in the 1920s a host of

unconventional forms and techniques suddenly flourished. Abstract photograms, photomontages composed of fragmented images, the combination of photographs with modern typography and graphic design in posters and magazine pages -all were facets of what artist and theorist László Moholy-Nagy enthusiastically described as a “new vision” rooted in the technological culture of the twentieth century.

Moholy-Nagy

An influential teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany, Moholy-Nagy championed unexpected vantage points and

playful printing techniques to engender a fresh rapport with the visible world. Other photographers in Germany, such as August Sander and Albert Renger-Patzsch emphasized the close observation of detail. And with the advent of the 35mm camera in the early 1930s, photojournalism and street photography became possessed of a new grace, deftness, and mobility.

|

| “Bosque de hayas“, Albert Renger-Patzsch |

The late 1920s saw a series of international exhibitions devoted to new vision photography. The most significant of these was Film und Foto, an exhibition held in Stuttgart in May–July 1929. The international show included approximately 1,000 works from Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States.

Roman Vishniac immigrated to Berlin in 1920, shortly after the formation of the Weimar Republic. He and his wife Luta settled in the Wilmersdorf district, home to a large community of affluent Russian-Jewish expatriates. Already an accomplished amateur photographer, Vishniac joined several of the city’s ubiquitous camera clubs; armed with his Rolleiflex and

Leica, he took to the streets, creating astute, often humorous observations of his adopted city.

In Berlin, his perspective as an outsider contributed to his inventive and dynamic images of life in the city, and marked his transformation from amateur hobbyist to

accomplished street photographer. His best, most intimate photographs were often taken in his own neighborhood, where he built a photo-processing lab.

Vishniac took full advantage of the city’s manifold resources, improving his technique and experimenting with modernist and avant-garde approaches to framing and composition – hallmarks of Weimar Berlin. This

prodigious body of early work became increasingly influenced by European modernism as he captured the daily life of the city; streetcar drivers, municipal workers and day laborers, marching students and children at play, bucolic park scenes and the intellectual café life of the bustling metropolis that was, in his words, “the world’s center of music, books, and science.”

|

| “Woman with Tiger“, Roman Vishniac |

The rise of Stalinism and Fascism in the 1930s would disillusion and silence many of the photographers associated with the new vision. By turns euphoric and despairing, prey to utopian optimism or deep spiritual disarray, the short period between the two world wars remains one of the richest in photographic history.

Art and a new type of architecture taught at “Bauhaus” schools reflected the new ideas of the time, and the artists in Berlin were influenced by other contemporary progressive cultural movements such as the Impressionist, Expressionist and Cubist painters in Paris. American progressive architects were also admired. Many of the new buildings constructed during this era followed a straight-lined, geometrical style of Art Deco; examples of the new architecture include the Bauhaus Building by Gropius, the Grosses Schauspielhaus, and the Einstein Tower.

Cinema in Weimar culture did not shy away from controversial topics, but dealt with them explicitly. Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst and starring Louise Brooks, deals with a young woman

who is thrown out of her home after having an illegitimate child and is forced to become a prostitute to survive. This trend of dealing frankly with provocative material in cinema began immediately after the

end of the War; in 1919, Richard Oswald directed and released two films that met with press controversy as well as actions by police vice investigators and government censors. Prostitution dealt with women

forced into “white slavery”, while Different from the Others dealt with a homosexual man’s conflict between his sexuality and social expectations.

But by the end of the decade, similar material met little, if any, opposition when it was released in Berlin theaters. William Dieterle’s Sex in Chains (1928), and Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929) dealt with homosexuality among men and women, respectively, and were certainly not censored.

Marlene Dietrich (1901 – 1992) was born on the outskirts of Berlin; her earliest professional stage appearances were as a chorus girl touring with Guido Thielscher’s Girl-Kabarett, various other vaudeville-style venues, and in Rudolf Nelson’s “revues” in Berlin. In 1922 Dietrich auditioned unsuccessfully for theatrical director at impresario Max Reinhardt’s drama academy; however, she soon found herself working in his theaters as a chorus girl and playing small roles in dramas, though she attracted little attention at first. She made her film debut playing a bit part in the film, The Little Napoleon (1923). Dietrich continued to work on stage and in film both in Berlin and Vienna throughout the 1920s. On stage, she had roles of varying importance in Frank Wedekind’s Pandora’s Box. It was in musicals and revues such as Broadway, Es Liegt in der Luft, and Zwei Krawatten that she began to build a name for herself; by the late 1920s Dietrich was also playing sizable parts on screen including Café Elektric (1927), Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame (1928) and Das Schiff der verlorenen Menschen (1929). In 1929 Dietrich landed the breakthrough role of Lola Lola, a cabaret singer who causes the downfall of a hitherto respected schoolmaster, in UFA’s production The Blue Angel (1930).

Dietrich continued to perform throughout most of her long and productive life.

But probably the most remarkable and best known product of 1920’s German cinema was the epic expressionist film Metropolis, written and directed by Fritz Lang in 1925.

A a pioneer work of science fiction movies it was the first feature length film of the genre: set in a futuristic urban dystopia, Metropolis was met with a mixed response upon its initial release. Because of

its long running-time and the inclusion of footage which foreign censors found

questionable it was cut substantially after the German premiere: large portions of the film were lost over the subsequent decades. Numerous attempts have been made to restore the film since the 1970s, culminating in a damaged print of Lang’s original cut being found in a museum in Argentina. After a long restoration process, the film has now been restored to 95% of the original.

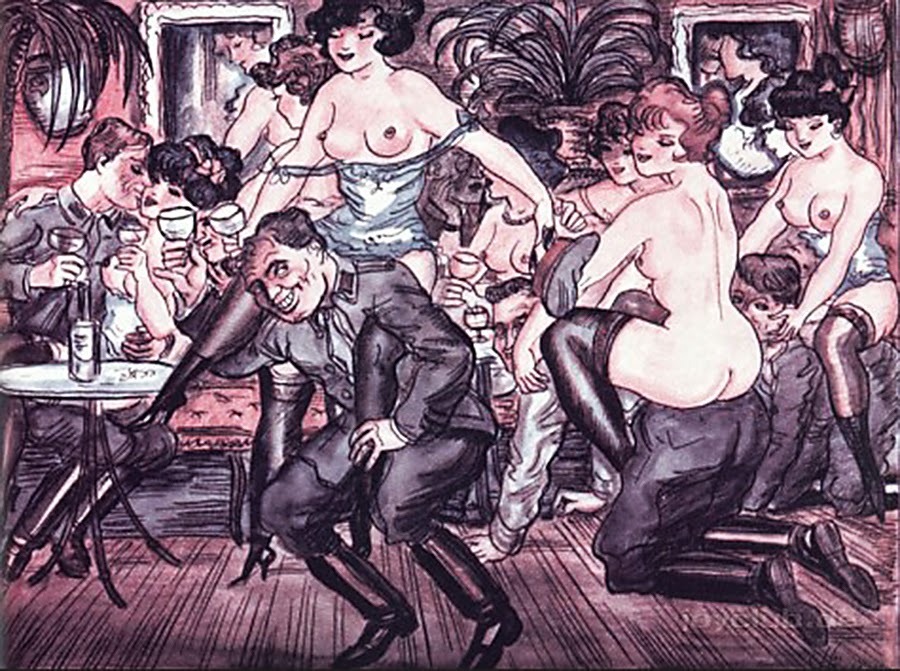

If America in the 1920s can be stereotyped by prohibition, gangsters, Jazz and the flappers, Paris would likewise take on the cliches of the “Lost Generation”, Surrealism and Art Deco.

But for Berlin in the 1920s, one thing stands out more than any other: an unbridled sexual decadence.

“Berlin nightlife, my word, the world hasn’t seen anything like it!

We use to have a first-class army; now we have first class perversions.” ~Klaus Mann, The Turning Point, 1942

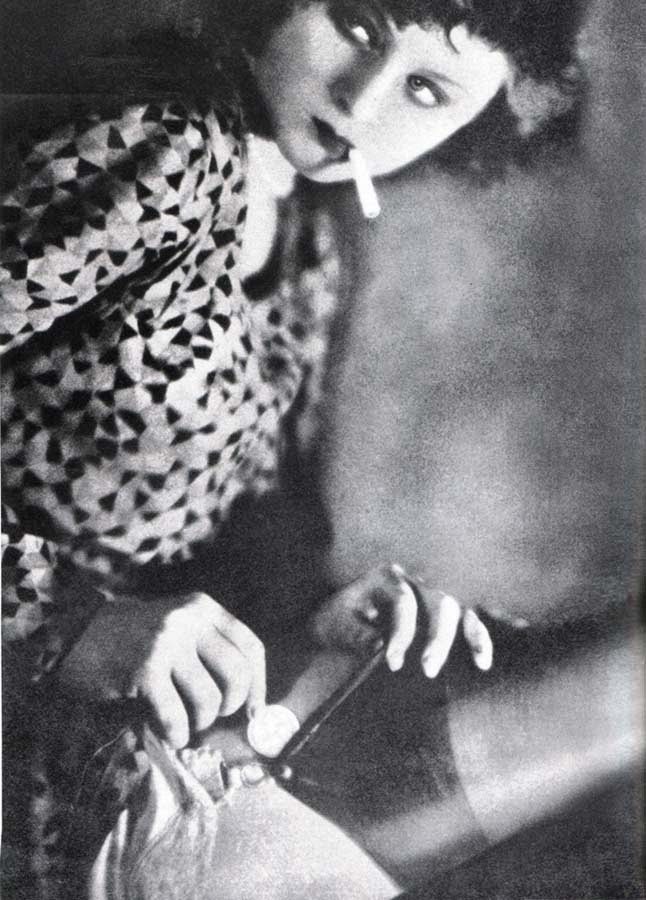

Prostitution rose rapidly in Berlin and throughout the areas of Europe left ravaged by World War I. This means of survival for desperate women (and sometimes men), became normalized to a degree in the 1920s. Prostitution was frowned on by respectable Berliners, but it continued to the point of becoming entrenched in the city’s underground economy and culture. Women with no other means of support first turned to the trade, then youths of both genders. By the end of the decade Berlin had literally thousands of prostitutes; working the streets, hotel lobbies, cafés and clubs. The number of women selling sex in

Berlin during the Twenties is impossible to calculate but

estimates range from 5,000 to 120,000 with another estimated 35,000 male prostitutes.

The war and hyperinflation may partially explain why so many people originally entered prostitution, but the introduction of the new currency and the end of hyperinflation did not make many of them abandon it. In fact, the Berlin prostitutes became even more popular once the currency stabilized.

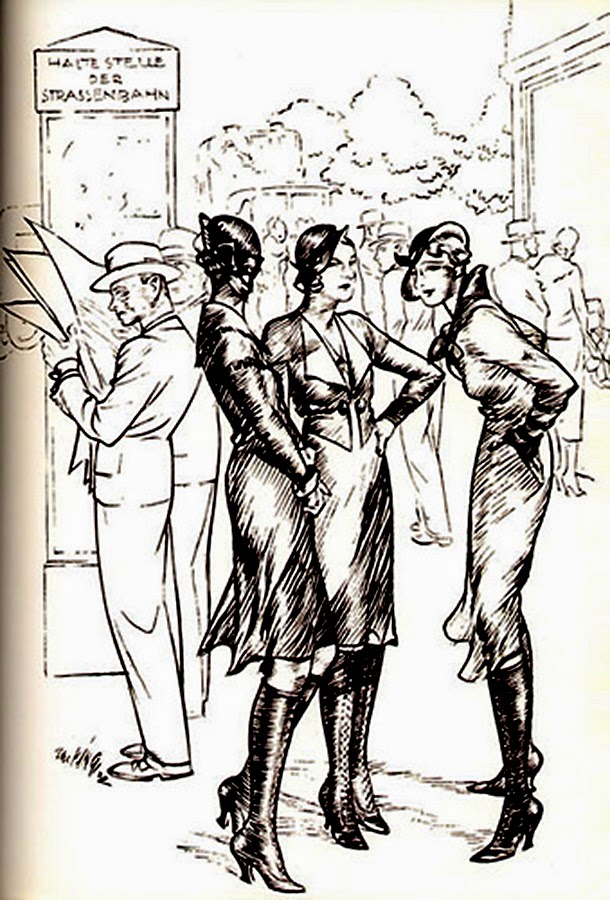

Although commercial sex was technically unlawful, some prostitutes had Kontroll cards giving them the “right” to work as prostitutes. To get a Kontroll card a prostitute had to go to one of eight vice-doctors every month. Unlike Paris, Berlin had no established red-light district or legalized brothels and prostitutes were prohibited from verbally soliciting customers or announcing their services in print. Instead, they had to signal their specialized activities by other means; through choosing specific locales, using evocative pseudonyms, or dressing in code. Prostitutes also had to change their clothing style frequently to distinguish themselves from the rest of the population, as Berlin’s middle class women often intentionally imitated the prostitutes’ fashions.

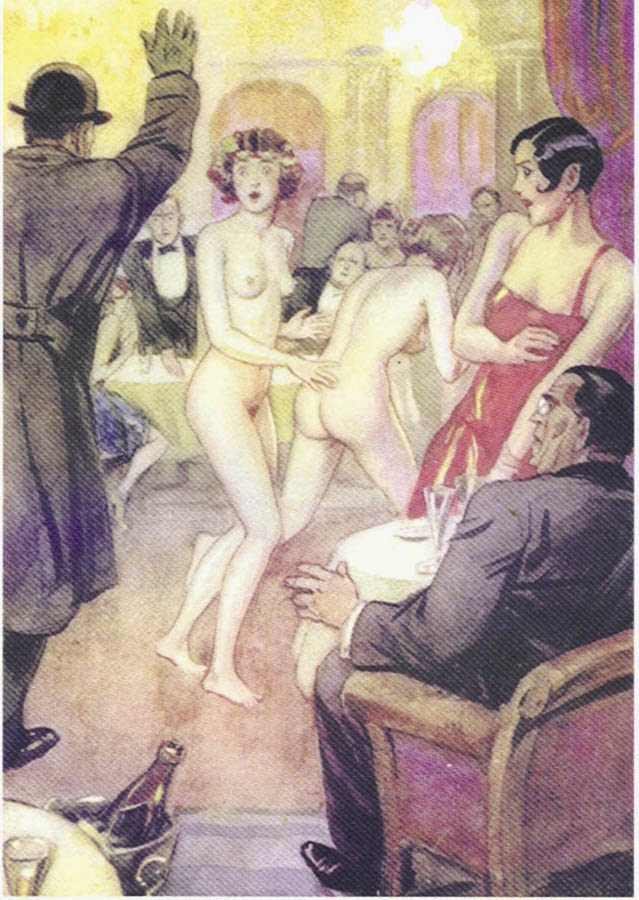

|

| “German Brothel in Ghent“, Alexander Szekely |

Erich Schütz

“And now we come to the most lurid Underworld of all cities -that of post-war Berlin. Ever since the declaration of peace, Berlin found its outlet in the wildest dissipation imaginable. The German is gross in his immorality, he likes his Halb-Welt or underworld pleasures to be devoid of any Kultur or refinement, he enjoys obscenity in a form which even the Parisian would not tolerate.”-Netley Lucas, Ladies of the Underworld, 1927

There were seventeen distinct varieties of female prostitutes in Weimar Berlin. Although relatively few, the “Boot Girls”, dominatrices near the Wittenberg Platz, provided the most ubiquitous local color. Their name came from their calf-length, patent-leather boots and laces whose colors suggesting particular services; i.e., women in

gold boots offered physical torture. Potential clients could readily purchase special guide books that decoded these various signals.

Arriving in Berlin during the inflation crisis of 1922–1923, Klaus Mann remembered walking past a group of the outdoor dominatrices: “Some

of them looked like fierce Amazons, strutting in high boots made of

green, glossy leather. One of them brandished a supple cane and leered at me as I passed by. ‘Good evening, Madam,’ I said. She whispered into my ear, ‘Want to be my slave? Costs only six billion and a cigarette. A bargain. Come along, honey!’”

Berlin soon became one of the Jazz Age’s primary destinations for sex tourists; its civic leaders even promoted this in 1927 with the oblique proclamation, “Jeder einmal in Berlin!” (Everyone Once in Berlin). Sexual decadence was one of the city’s most lucrative industries.

|

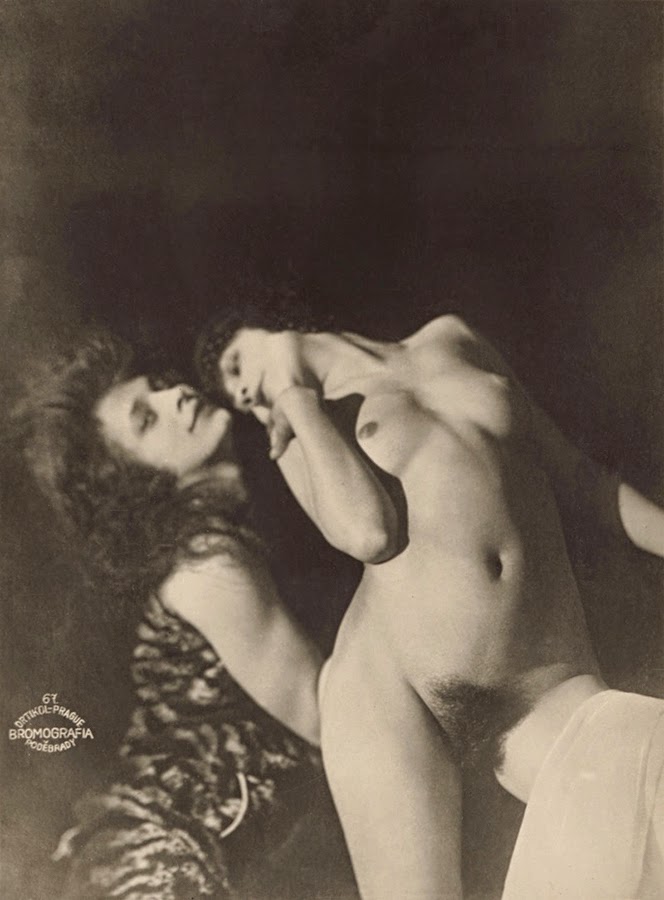

|

| “Two female nudes“, Heinz von Perckhammer |

Untitled, Frantisek Drtikol Untitled, Heinz Von Perckhammer “Hot Sisters“, Margit Toth

|

| “Careful, I’m not a man!” “That’s okay, I’m not a woman”, Lustige Blätter |

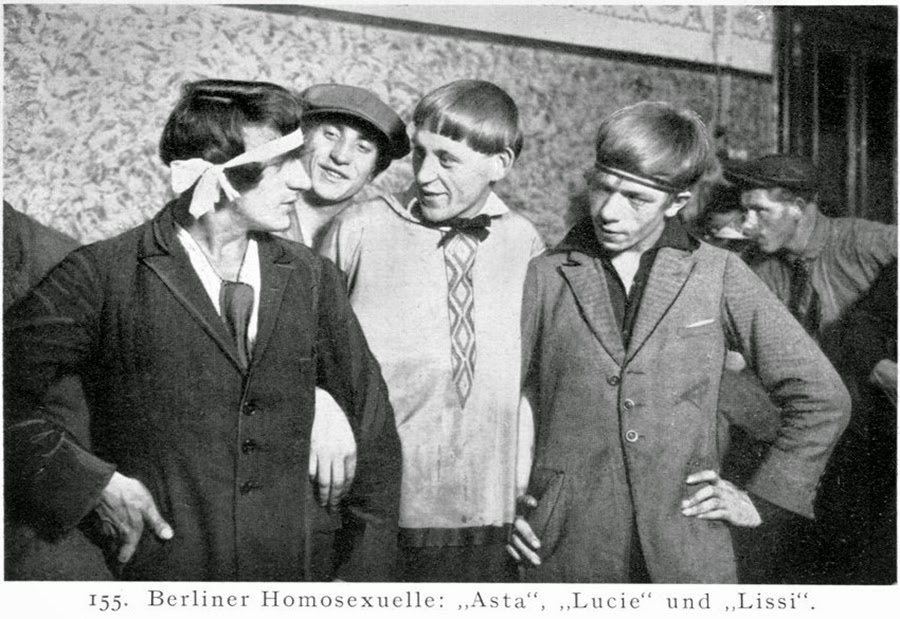

Even before World War I, Berlin had a lively homosexual subculture. The areas around the Friedrichstadt had 38 cabarets devoted to male homosexuals, and the numbers of clubs tripled after the collapse of the

mark. By 1930 Berlin had at least 35,000 “Line-Boys” (male prostitutes who stood in rows along certain streets) and the numbers grew every month. The

increasing numbers of male prostitutes was also officially blamed on the economy, and partly on the tolerance of female prostitutes. Local statistics however showed that a simple increase in demand

was the primary cause.

|

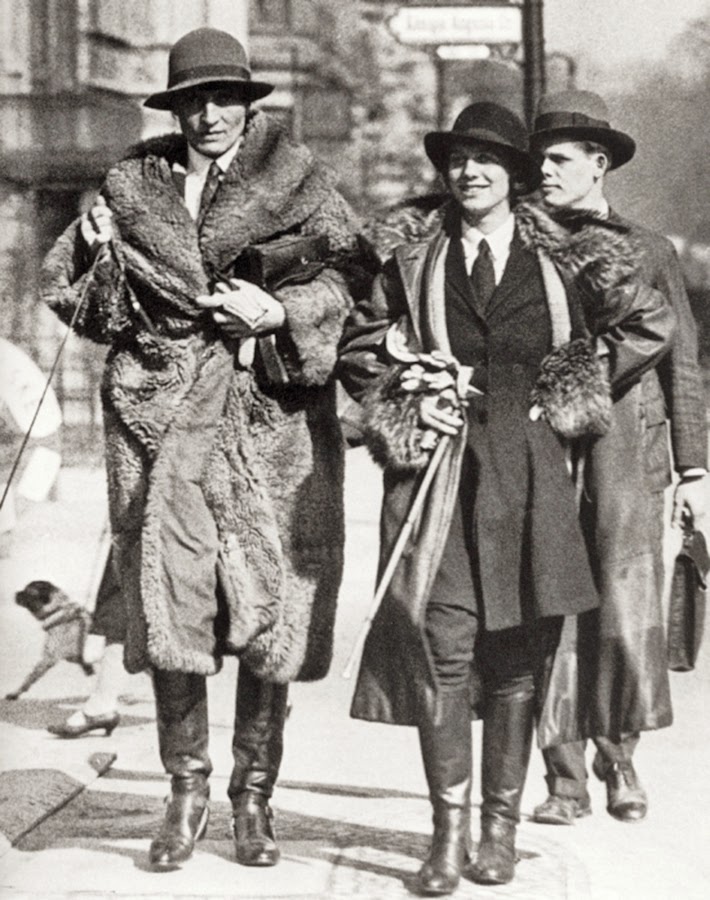

| “Butch” Lesbians in Berlin |

A byproduct of the tolerance for prostitution appears to have been a more visible tolerance for diverse sexual behavior, mainly visible in the boom in the city’s underground homosexual culture among both men and women. Sexual experimentation became more common: according to the German writer and historian Laura Méritt; “…there were also a lot of lesbian prostitutes. Ladies of the high society lived together with their girls, or the girls accomodated them to earn extra money. More than 30 per cent of the prostitutes along Kurfürstendamm were lesbians, however, back then the butch walked the streets and her femme stayed in the pub and got drunk with her friends. They didn’t want their women to work, they were the ones who brought home the money. This ‘classic’ role allocation also caused the development of a lesbian dress code: the women wore the boots they were wearing on the construction sites, the hair was short because it was more practical and less dangerous when working with machinery. Many lesbians “hit” their johns not out of self-interest but because it was demanded, but they still slept at home with their (female) spouses.”

In addition to outright prostitution, Berlin boasted some 500 erotic nightclubs including many venues specifically directed towards homosexuals and lesbians; sometimes transvestites of one or both genders were admitted, but there were also at least 5 known establishments exclusively for a transvestite clientele.

There were several nudist clubs, and many other well-known venues where underground figures such as crime bosses gathered.

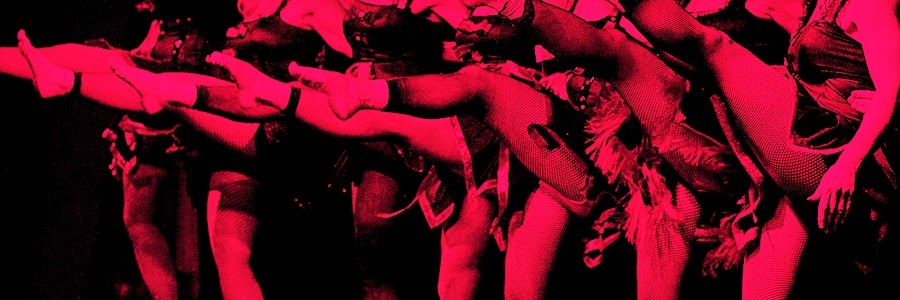

Artists in Berlin became fused with the city’s underground culture as the borders between cabaret and legitimate theatre blurred.

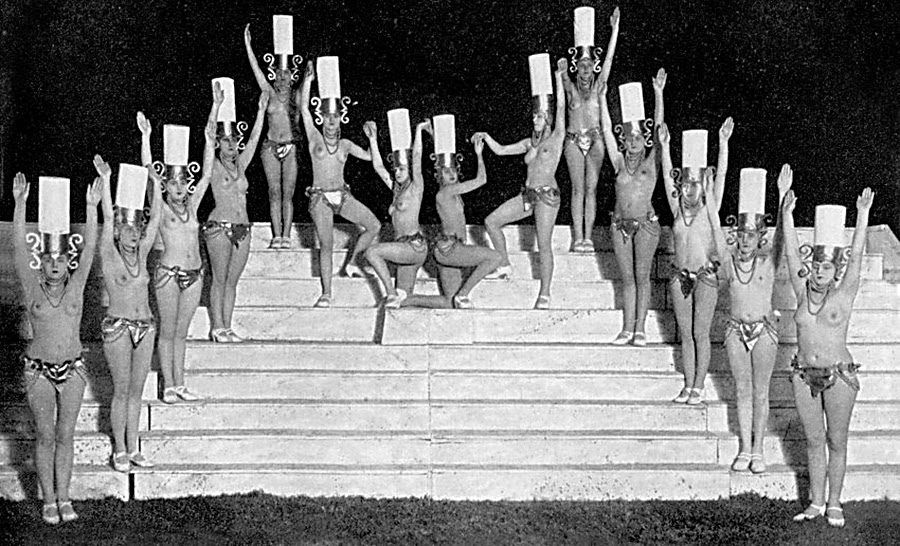

The later Weimar era has particularly become known for its Kabarett, the popular restaurants and

nightclubs where patrons sat at tables, entertained by a

procession of singers, dancers and comedians atop a small stage. Cabaret

was actually a French invention dating back to the 1880s, but the German form was slightly more conservative and low-key -at least in flamboyant costume if not in decadence.

Cabarets had become enormously popular across Europe after World War I, and nowhere were they more popular than Germany. Berlin’s first kabarett dated back to 1901, though German clubs were not permitted to allow bawdy humor, provocative dancing or political satire during the Kaiser’s reign. The lifting of censorship by the Weimar government’s

saw Germany’s nightclubs transform and flourish.

Along with open displays of nudity (most German cabarets had at least some topless dancers), the cabarets also provided Germans with an outlet for political views and criticism. A good deal of the stand-up comedy on cabaret stages was

done by ‘political humorists’, who ridiculed all points along the

political spectrum. Some of it was personal rather than political: Friedrich Ebert was mocked for his

weight, and the appearance and mannerisms of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler were heavily ridiculed during the late 1920s. But other cabaret performers asked more substantial political questions; Mischa Spoliansky’s popular tune, It’s All A Swindle (1931), was a later example:

“Politicians are magicians

Who make swindles disappear

The bribes they are taking

The deals they are making

Never reach the public’s ear

The left betrays, the right dismays

The country’s broke – and guess who pays?

But tax each swindle in the making

Profits will be record breaking

Everyone swindles some

So vote for who will steal for you.”

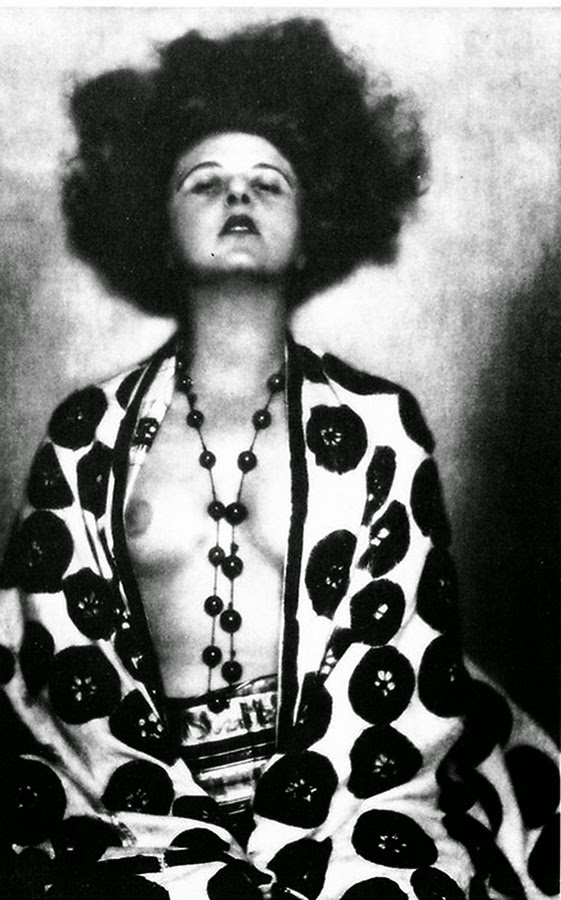

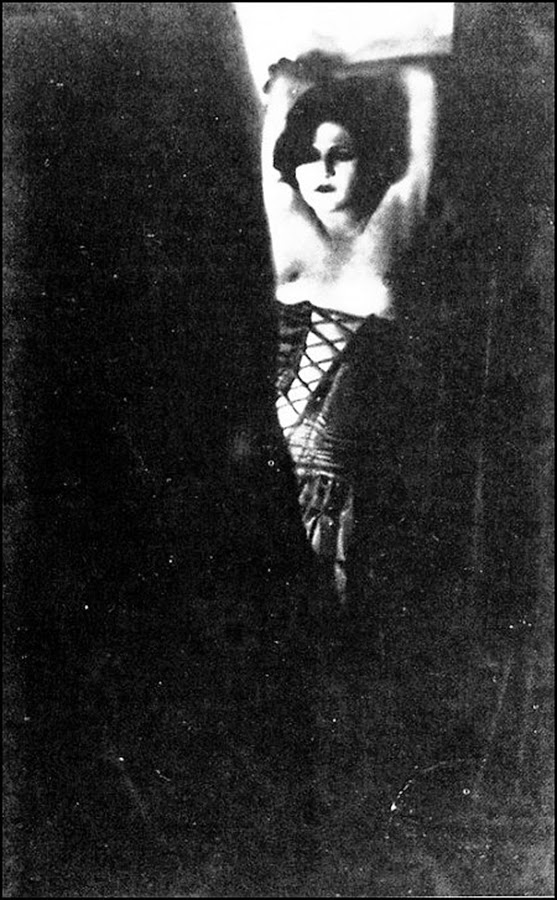

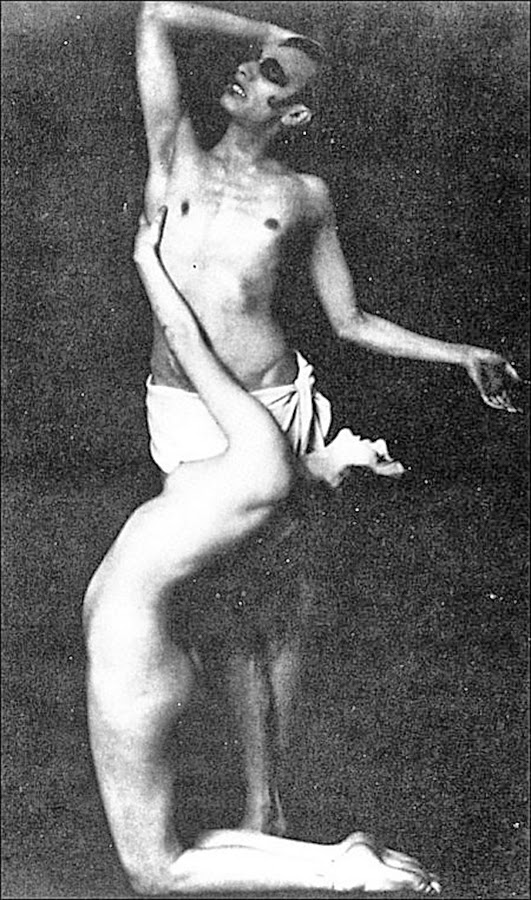

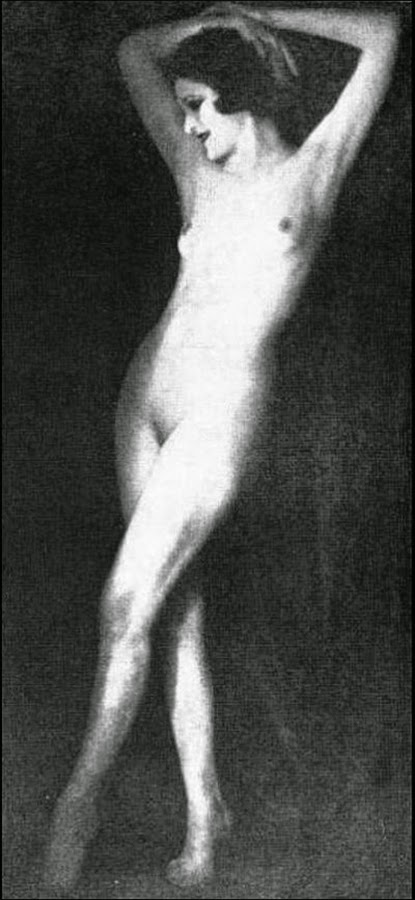

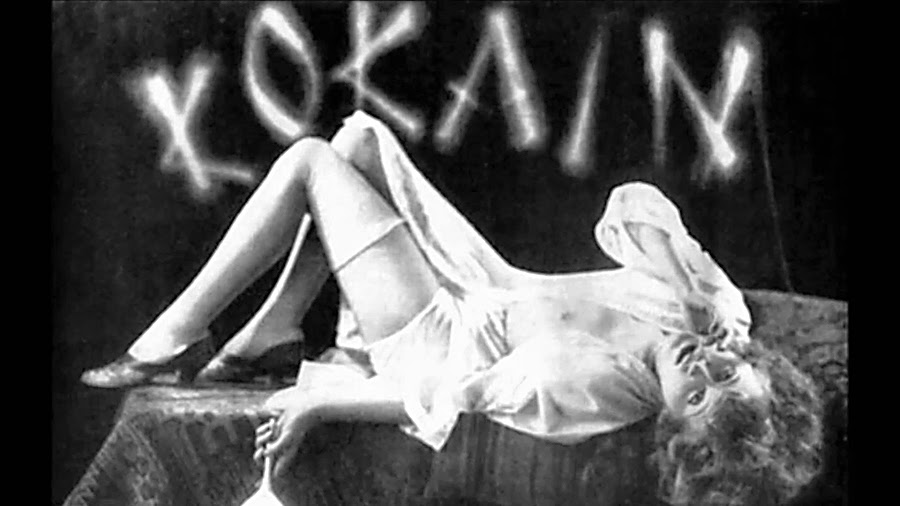

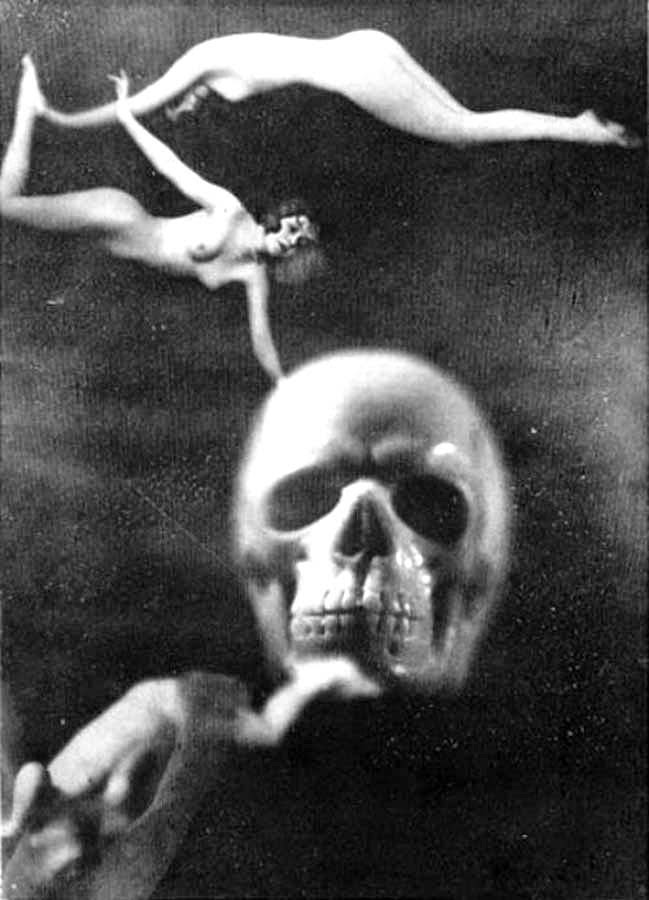

The dancer and actress Anita Berber became notorious throughout the city and beyond for her erotic performances (as well as her cocaine addiction and erratic behavior). Born in Leipzig to musician parents who later divorced, she was raised mainly by her grandmother in Dresden. By the age of 16 she had moved to Berlin and made her debut as a cabaret dancer; within two years she was working in film, and she began dancing nude in 1919. Scandalously androgynous,

Berber quickly made a name for herself.

With her hair cut fashionably into a short bob and frequently dyed a bright red, Berber wore heavy dancer’s make-up which on the common black-and-white film of the time came across in jet black lips and eyes. Her performances broke boundaries with their androgyny and total nudity, but it was her public appearances that really challenged taboos: Berber’s overt drug addiction and bisexuality were matters of regular public chatter. In addition to her addiction to cocaine, opium and morphine, one of Berber’s favorites was chloroform and ether mixed in a bowl. This would be stirred with a white rose, the petals of which she would then eat.

|

| Above: Anita Berber, various productions 1919 – 1928 |

Aside from her addiction to narcotic drugs, Berber was also a heavy alcoholic. In 1928 she suddenly gave up alcohol completely, but died later the same year at the age of 29. She was said to be surrounded by empty morphine syringes.

Crime in general had developed in parallel with prostitution in the city, beginning with a surge in petty thefts and other minor crimes linked to the need to survive in the war’s aftermath. But Berlin eventually acquired another reputation as a hub of drug trafficking (particularly for cocaine, heroin and narcotics) and for its thriving black market.

|

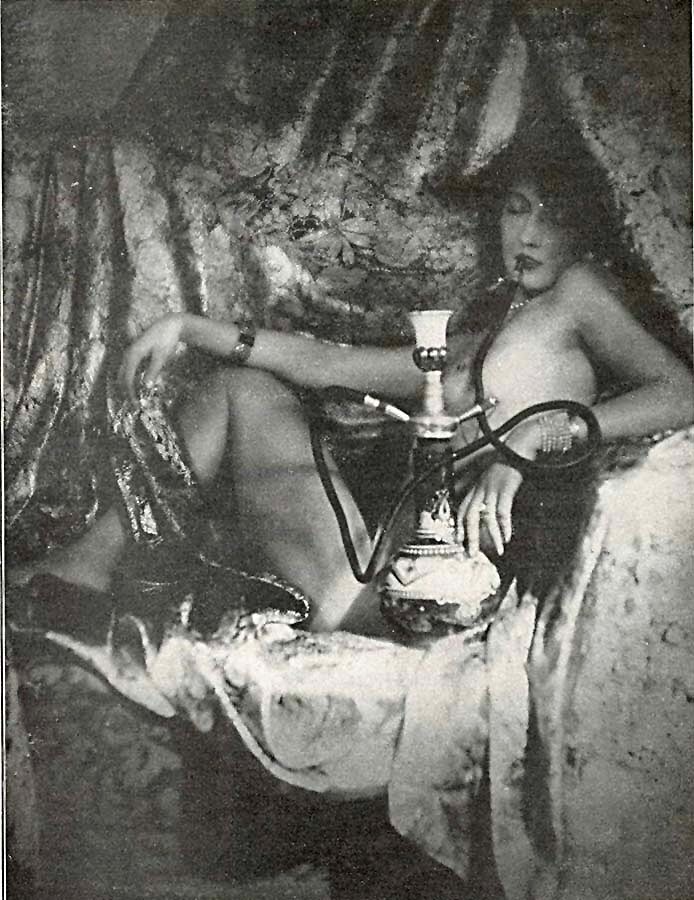

| Above: Photography by Atelier Manassé, Berlin, 1924 – 1930 |

Not everyone, obviously, was happy with the changes taking place in Weimar culture. Conservatives and reactionaries feared that Germany was betraying her traditional values by adopting popular social values from abroad, particularly from the American films.

New York had become the global capital of fashion, Hollywood was inventing the new culture, and Germany was highly susceptible to Americanization because of the close economic links brought about by the Dawes plan.

In 1929 the German economy was greatly affected by the onset of America’s Great Depression. The economy had been supported by loans through the Dawes Plan (1924) and the Young Plan (1929); when American banks withdrew those loans to German companies, unemployment grew rapidly and in September 1930 a political earthquake shook the republic to its foundations. The Nazi Party entered the Reichstag with 19% of the popular vote and the fragile coalition system by which every chancellor had governed collapsed like a house of cards. The Third Reich had begun.

The end of the Weimar Republic, an era torn between conflicting elements of enlightenment and perversion, had come. And perversions on a grander scale than any of its citizens could imagine crouched, snarling, on the horizon.

References:

Berlin in the 1920s: Wellesley College Department of German

Inventory / Everyone Once in Berlin!; Mel Gordon, Cabinet Magazine Issue 32 Winter 2008/09

Weimar Berlin, City of Whores; Boomswing.com

Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin; Mel Gordon, 2008

weimarart.blogspot.com

www.cabaret-berlin.com

The New Vision of Photography: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Roman Vishniac; Berlin Street Photography, 1920s: Maya Benton

Comments

The Sun Between the Storms; Part II, Berlin — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>