The son of Danish immigrants, William Herbert Mortensen was born on January 27, 1897 in Park City, Utah. He served with the United States Infantry during World War I, and on his enlistment he recorded his occupation as “painting”. After his discharge in 1919 Mortensen briefly studied illustration at the Art Students League in New York City, but left in 1920 and traveled to Greece “to sketch”.

On his return to Utah later the same year, he taught art at the East Side High School in Salt Lake City but at the end of the school year he quit and escorted Fay Wray, a friend of his sister, to Hollywood.

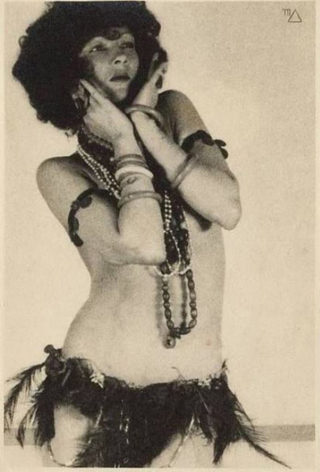

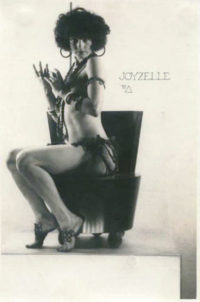

Mortensen evidently knew someone in Los Angeles who put him in contact with film director King Vidor. In 1921 he began painting scenery, making masks, and engaging in various other art-related services for the burgeoning film industry: simultaneously he began work at Western Costume Company photographing silent film stars in costume. A canny showman, he observed Hollywood’s PR machinery and understood that he could control how others perceived him.

In 1924 Moertensen married Courtney Crawford, a librarian, and moved into her home on Hollywood Blvd where he opened a studio that he maintained until 1931. In 1926 he worked for Cecil B. DeMille on the King of Kings, shooting all the stills with a small format camera during filming. He also began to enter and show in photographic salons in American and Europe; his work was published in Photograms of the Year, American Annual of Photography, Vanity Fair, The Los Angeles Times, and others.

In 1924 Moertensen married Courtney Crawford, a librarian, and moved into her home on Hollywood Blvd where he opened a studio that he maintained until 1931. In 1926 he worked for Cecil B. DeMille on the King of Kings, shooting all the stills with a small format camera during filming. He also began to enter and show in photographic salons in American and Europe; his work was published in Photograms of the Year, American Annual of Photography, Vanity Fair, The Los Angeles Times, and others.

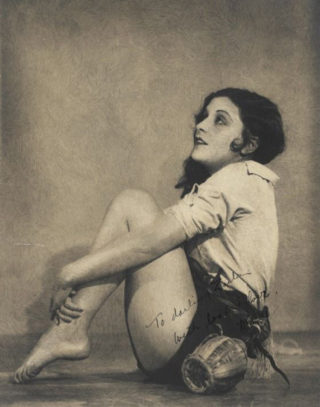

In 1931 Mortensen somewhat mysteriously moved to Laguna Beach and opened a studio on Pacific Coast Hwy (then called South Coast Hwy), the first of four spaces that he rented over the next thirty years. His school, the Mortensen School Of Photography, officially opened that same year. He was divorced, and claimed that the move was due to the depression and the changes in Hollywood brought about by the new sound films. But Fay Wray, writing in On The Other Hand, said that photographs of her taken years before by Mortensen appeared in a movie magazine in 1928; although not nude, they were deemed “immodest” for the time, and the pictures were run with an account of her unchaperoned trip to Hollywood seven years earlier. Her mother and husband, along withParamount’s publicity arm, had pressured Mortensen to sign a document denying the pictures and the story.

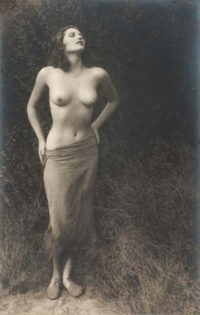

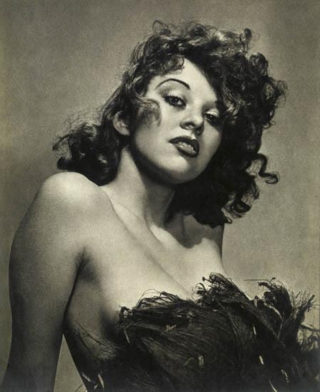

In 1933 Mortensen married Myrdith Monaghan, and met George Dunham who became a friend and model. He began a long writing collaboration with Dunham, yielding 9 books in multiple editions and printings, 4 pamphlets, and over 100 articles in magazines and newspapers. Both Myrdith and Dunham proved to be his most significant models, helping him to produce his most important body of work. Through the popularity of his books and articles along with his photographic imagery he became one of the most sought-after photographers and writers about photography during the 1930s.

In 1933 Mortensen married Myrdith Monaghan, and met George Dunham who became a friend and model. He began a long writing collaboration with Dunham, yielding 9 books in multiple editions and printings, 4 pamphlets, and over 100 articles in magazines and newspapers. Both Myrdith and Dunham proved to be his most significant models, helping him to produce his most important body of work. Through the popularity of his books and articles along with his photographic imagery he became one of the most sought-after photographers and writers about photography during the 1930s.

He was also an astute businessman who turned his fame into a series of “Mortensen-approved” and branded photographic products, one of the first artists to do so.

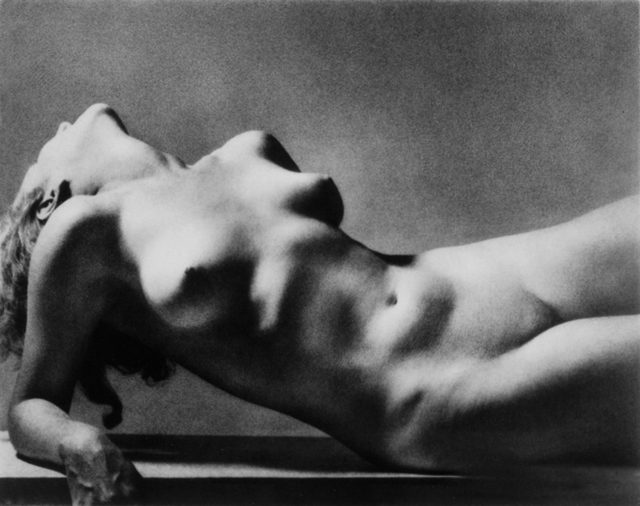

Mortensen was a restless and relentless darkroom technician. He invented his own texture screens, an abrasion tone process which employed the use of a razor blade to carefully scrape away emulsion off the print, the Metalchrome process (a chemical color process that utilized chemical toning to turn black and white prints into color prints), and a non-silver pigment process that incorporated two colors registered together to change a black-and-white negative into a color print. He was also master of the bromoil transfer processes and the paper negative.

During all this he kept his hand in etching processes learned from his early days in New York. There are some small prints showing that Mortensen also experimented with poured or painted-on developer on film. He then made prints using these as a background, working figures and objects into the abstract pattern.

Using the fame created from his publications he marketed his school, his texture screens, an abrasion tone kit, and a “viewing glass” which helped the photographer to see in monochrome. He also developed a mass-production approach for sales of his images. He was, in a sense, photography’s first superstar, leveraging the celebrity he created for himself to merchandise products bearing his name.

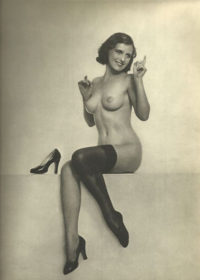

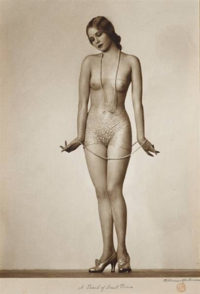

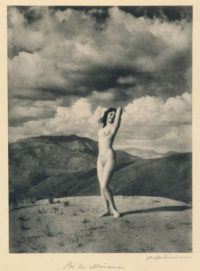

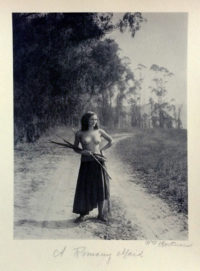

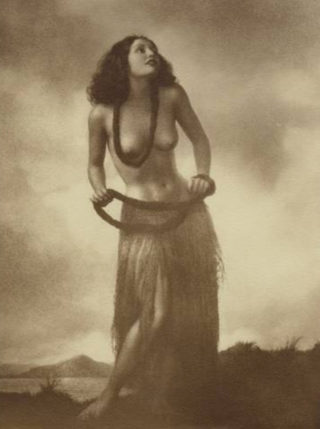

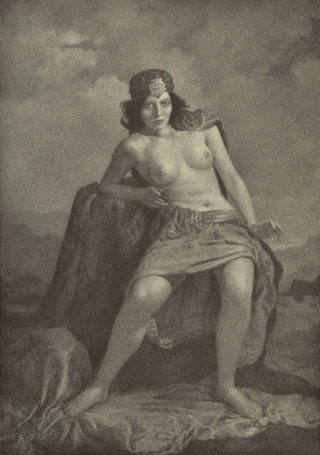

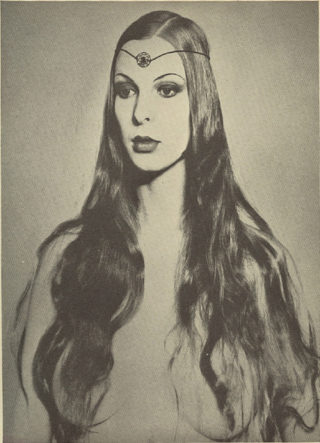

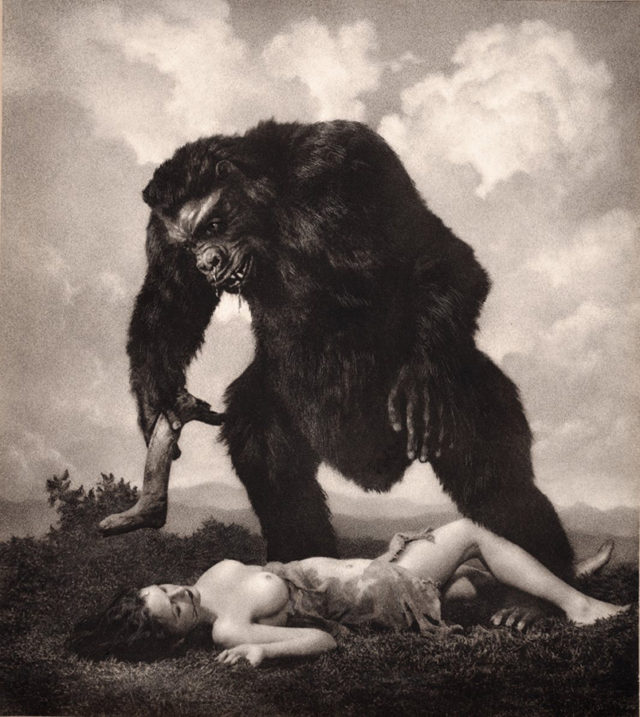

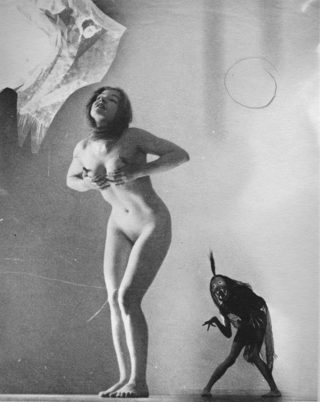

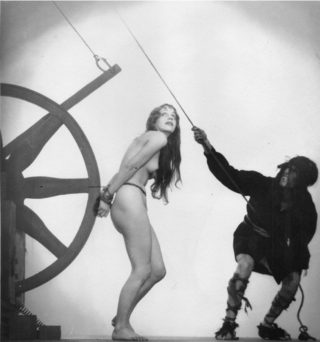

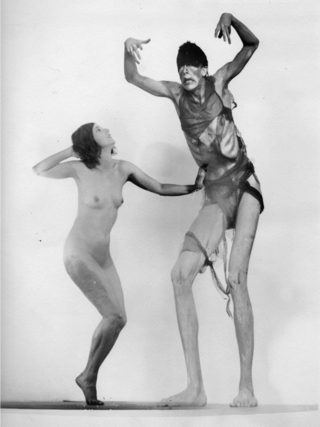

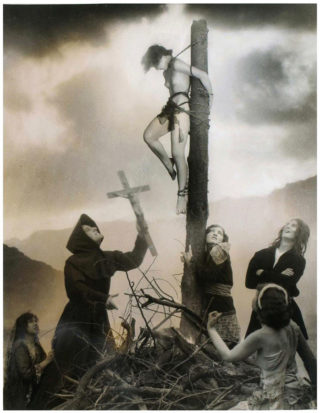

But Mortensen’s defense of romanticist photography led him to be ostracized from most authoritative canons of photographic history. Mortensen’s distinctive pictorial images were highly orchestrated, heavily manipulated, and melodramatic; his character studies were given universal attributes; idealized nudes and so-called “grotesques,” which pictured the darker side of humanity—a rarity for pictorialists. Ansel Adams variously referred to Mortensen as the “Devil”, and “the anti-Christ.” By the late 1930’s the realistic photojournalism emerging from World War II correspondents and carried in national news magazines caused Mortensen’s more posed and contrived photos to fade from the public mind.

In the early 1960s Mortensen returned to painting. He was largely forgotten by the time of his death from leukemia in 1965.

Although grounded in the 19th century romanticism of Symbolist art, Mortensen had a postmodernist’s interest in the symbolic nature of photography. He was the first American visual artist to thoroughly explore grotesque imagery. He pushed the bounds of commonly accepted photographic subject matter, which enraged his foes and ensured his obscurity by the purveyors of photographic history. Happily, however, all of these factors also meant that Mortensen’s work would have importance long after his death. Although the forces of photographic change savaged him in the mid 20th century, his unique vision and methods foretold the momentous upheavals facing photography at the turn of the 21st century.

References and More:

George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive: William Mortensen

OPUS HYPNAGOGIA; Sacred Spaces of the Visionary and Vernacular

The Antichrist of Early-20th-Century Photography; Claire Voon, Hyperallergenic.com

The Grotesque Eroticism of William Mortensen’s Lost Photography; Larry Lytle, Vice.com

THE COMMAND TO LOOK: The Story of William Mortensen, Part I by Larry Lytle

PDF Files:

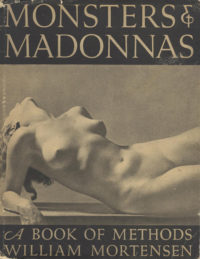

Monsters and Madonnas: A Book of Methods by William Mortensen

A Pictorial Compendium of Witchcraft; William Mortensen, 1897–1965

The Command to Look: A Formula for Picture Success by William Mortensen