The precise origin of absinthe is unclear; medical use of wormwood dates back to ancient Egypt, and is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus, c. 1550 BC. Wormwood extracts and wine-soaked wormwood leaves were used as remedies by the ancient Greeks and there is evidence of a wormwood-flavoured wine, absinthites oinos, in ancient Greece.

The first clear evidence of absinthe as a distilled spirit with the inclusion of green anise and fennel dates to the 18th century. Legend attributes its modern beginnings to an all-purpose patent remedy created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet,

Switzerland around 1792.

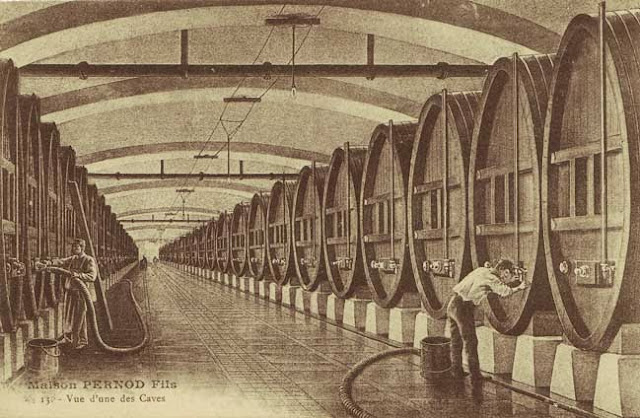

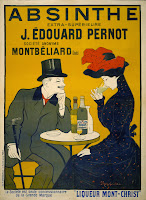

Ordinaire’s recipe was passed on to the Henriod sisters of Couvet, who sold absinthe as a medicinal elixir (some accounts reverse the origins and claim that the Henriod sisters created the recipe). In either case, a certain Major Dubied acquired the formula from the sisters and opened the first absinthe distillery in 1797 with his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod, in Dubied Père et Fils, Couvet. In 1805 they built a second distillery in Pontarlier, France under the company name Maison Pernod Fils, which remained one of the most popular brands in France until the drink was banned in 1914.

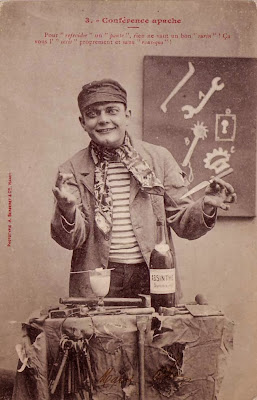

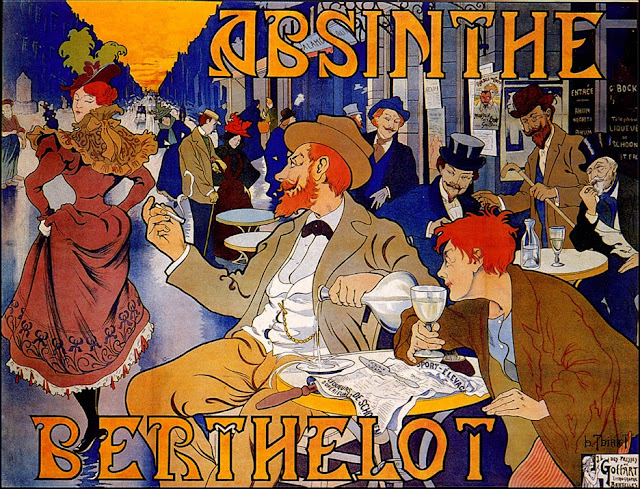

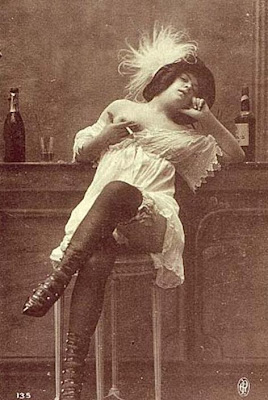

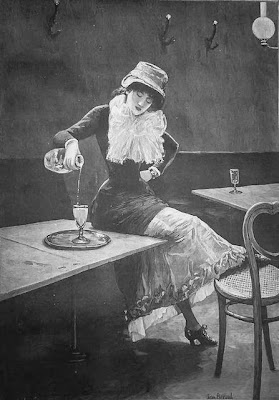

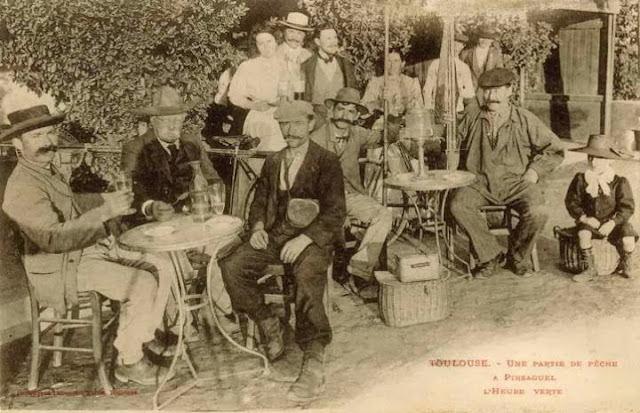

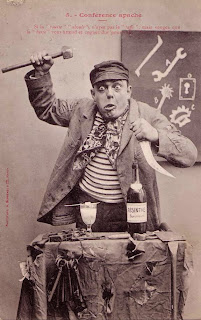

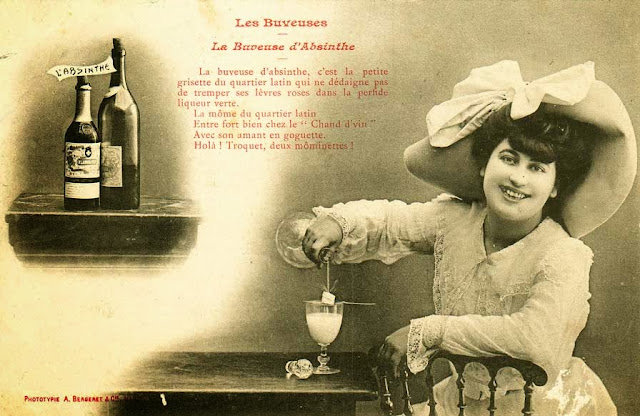

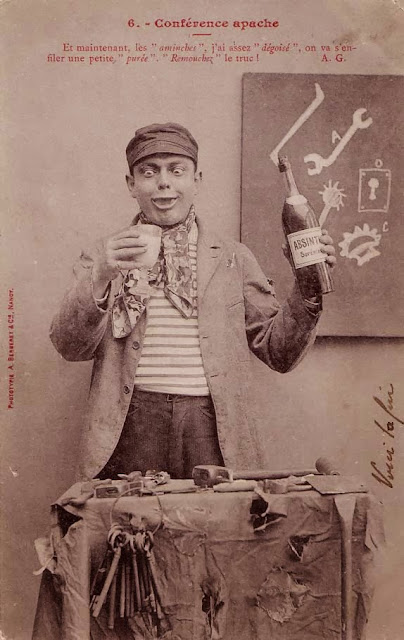

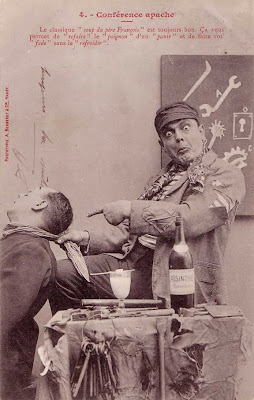

Absinthe’s popularity grew steadily through the 1840s due to its use as a malaria preventive for French troops in North Africa during the French campaigns of the 1840s. As the army returned home they brought their taste for absinthe with them and the custom of drinking absinthe gradually became so popular in bars and cafés that by the 1860s 5 p.m. was generally known as l’heure verte (“the green hour”). Absinthe was popular among all social classes, and by the 1880s mass production had caused the price to drop sharply. By 1910 the French alone were drinking 36 million liters of absinthe per year (compared to an annual consumption of only 5 billion liters of wine).

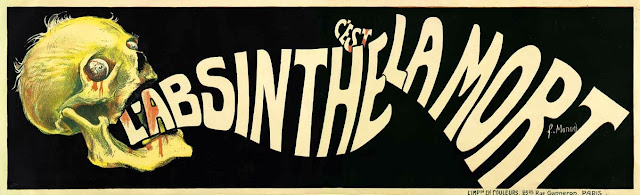

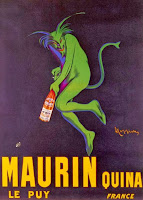

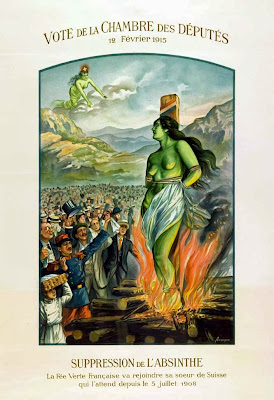

Absinthe has often been portrayed as an addictive psychoactive drug due to trace amounts of the chemical compound thujone; by the early 1900’s it had become a primary target of both the temperance movement and French wine producers who saw its popularity as a threat to their sales, already decimated by the phylloxera louse that had destroyed most of the vineyards by 1890. By 1915 it had been banned in the

Absinthe has often been portrayed as an addictive psychoactive drug due to trace amounts of the chemical compound thujone; by the early 1900’s it had become a primary target of both the temperance movement and French wine producers who saw its popularity as a threat to their sales, already decimated by the phylloxera louse that had destroyed most of the vineyards by 1890. By 1915 it had been banned in the

United States and throughout much of Europe. However, absinthe has never been demonstrated to be any more dangerous than ordinary spirits; the psychoactive properties attributed to thujone were much exaggerated, although its high alcohol content and immense popularity had contributed to a massive surge in alcoholism. A revival of absinthe began in the 1990s following the adoption of modern food and beverage laws in the European Union that finally removed barriers to its production and sale. Today over 200 brands of absinthe are being produced in several countries including France, Switzerland, USA, Spain, and the Czech Republic.

In the US the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

(TTB) effectively lifted the absinthe ban in 2007, and has since

approved many brands for sale in the U.S. market. Some restrictions still apply, including specifications that the product must be thujone-free (thujone content less than 10 ppm (equal to 10 mg/kg), the word “absinthe” can not be used as the brand name or stand alone on the label, and the packaging cannot “project images of hallucinogenic, psychotropic or mind-altering effects.” Absinthe imported in violation of these regulations is subject to seizure at the discretion of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Absinthe is a distilled spirit with a traditionally high alcohol

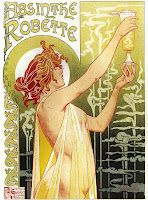

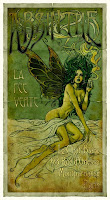

content (45–74% ABV / 90-148 proof). It is flavored with anise along with the flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium (a.k.a. “grand wormwood”); other botanicals may include green anise, sweet fennel, and various medicinal and culinary herbs. Traditionally absinthe

has a natural green color and is commonly referred to in historical literature as “la fée verte” (the green fairy), but it may also be colorless. Although it is sometimes referred to as a liqueur, absinthe is not traditionally bottled with added sugar and is therefore classified as a spirit. Due to the high alcohol content absinthe is traditionally diluted with water prior to being consumed.

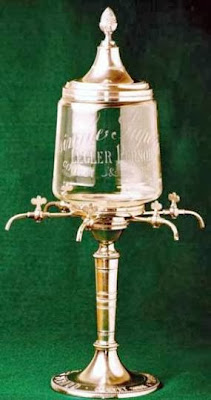

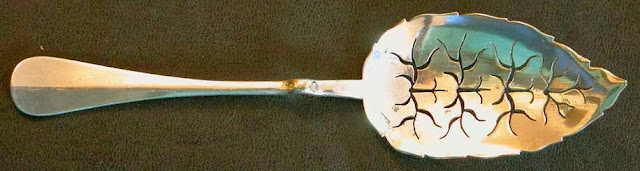

Absinthe is traditionally prepared in the French Method, placing a sugar cube on top of a specially designed slotted spoon,

and then placing the spoon on the glass which has been filled with a measure of absinthe. Iced water is then poured or dripped over the sugar cube so that it is slowly and evenly displaced into

the spirit, with the final preparation usually containing app. 1 part absinthe and 3-5 parts water. As water dilutes the spirit the components with poor water solubility (mainly anise, fennel, and star anise) come out of solution and cloud the drink; the resulting opalescence is called the louche (“opaque”). This process also releases herbal aromas and subtleties that are otherwise muted within the neat spirit. A number of glasses have been specifically designed for the French absinthe

preparation ritual, typically fashioned with a dose line, bulge, or bubble in the lower portion denoting how much

absinthe should be poured. One “dose” of absinthe ranges anywhere from around 1-1.5 fluid ounces (30-45 ml).

The Bohemian Method is a more recent invention that utilizes an absinthe (or pure alcohol) soaked sugar cube which is set alight on the spoon then dropped into a glass containing one shot of the spirit which is then itself ignited: finally a shot glass of water is added to douse the flames. This process destroys most of the flavors along with the alcohol and is generally considered a gimmick, frowned upon by experienced absintheurs. The Czechs are credited with inventing the Bohemian Method in the 1990s possibly because Czech “absinth” does not louche rendering the traditional French method useless.

Absinthe is traditionally categorized into several grades; ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, and Suisse in order of increasing alcoholic strength and quality, although contemporary brands may simply be classified as distilled or mixed according to production method. Distilled absinthe is generally considered far superior, but the claim of being ‘distilled’ makes no guarantee as to the quality of its base ingredients or the skill of its maker. Most countries (except Switzerland) presently do not possess a legal definition of absinthe and producers are free to label a product ‘absinthe’ or ‘absinth’ whether or not it bears any resemblance to the traditional spirit. Currently there are five basic styles:

Absinthe is traditionally categorized into several grades; ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, and Suisse in order of increasing alcoholic strength and quality, although contemporary brands may simply be classified as distilled or mixed according to production method. Distilled absinthe is generally considered far superior, but the claim of being ‘distilled’ makes no guarantee as to the quality of its base ingredients or the skill of its maker. Most countries (except Switzerland) presently do not possess a legal definition of absinthe and producers are free to label a product ‘absinthe’ or ‘absinth’ whether or not it bears any resemblance to the traditional spirit. Currently there are five basic styles:

- Blanche absinthe (also referred to as la Bleue in Switzerland) is bottled directly following distillation and reduction, and is uncoloured (clear). The name la Bleue was originally a term used for bootleg Swiss absinthe, but has become a popular term for post-ban-style Swiss absinthe in general.

- Verte (“green”) absinthe begins as a blanche but is altered by a separate mixture of herbs steeped into the clear distillate. This confers a peridot green hue and an intense flavor. Vertes represent the prevailing type of absinthe found in the 19th century, although artificially colored green absinthes may also claimed to be “verte”.

- Absenta (Spanish) is sometimes associated with a regional style that differs slightly from its French origins. Traditional absentas may taste slightly different due to their use of Alicante anise, and often exhibit a characteristic citrus flavor.

- Hausgemacht (German for “home-made”, often abbreviated as HG) refers to clandestine absinthe that is home-distilled in small quantities for personal use. Clandestine production increased most notably in Switzerland after absinthe was banned; although the ban has been lifted in Switzerland, some distillers have not legitimized their production due to high taxes on alcohol and the mystique of being underground.

- Bohemian-style absinth (without the “e”, also referred to as Czech-style absinthe or anise-free absinthe) is best described as a wormwood bitters. It is produced mainly in the Czech Republic, and only contains wormwood with a high alcohol content. Czech absinth does not louche, and is typically served in the Bohemian manner.

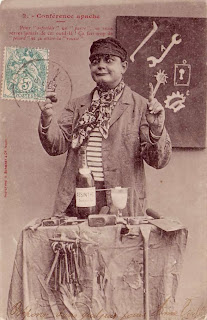

Absinthe has been frequently and improperly described in modern times as being hallucinogenic; in the 19th century the French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan studied 250 cases of alcoholism and claimed that those who drank absinthe experienced more rapid-onset hallucinations as compared to those drinking ordinary alcohol. In the 1970s a scientific paper suggested that thujone’s structural similarity to THC presented the possibility of THC receptor affinity although that theory was conclusively disproved in 1999.

Still, the debate over whether absinthe produces mental effects beyond those of simple alcohol is not conclusively resolved. A commonly reported experience is a ‘clear-headed’ feeling of

inebriation, described as ‘lucid drunkenness’. Chemist, historian and absinthe distiller Ted Breaux has claimed that the alleged secondary effects of absinthe may be caused by the fact that some of the herbal compounds in the drink act as stimulants while others act as sedatives, creating an overall lucid effect.

Tests of thujone toxicity in mice showed an oral LD50 of about 45 mg thujone per kg of body weight, which represents far more absinthe than could be realistically consumed (the high percentage of alcohol would result in mortality long before thujone could become a factor). In documented cases of acute thujone poisoning as a result of oral ingestion the source of thujone was non-absinthe related sources such as common essential oils (which may contain as much as 50% thujone). The European Union permits a maximum thujone level of 35 mg/kg in alcoholic beverages where Artemisia species is a listed ingredient, and 10 mg/kg in other alcoholic beverages.

Further Reading:

absinthes.com

la Fée Verte’s Absinthe House

Le Musée Virtuel de l’Absinthe

Absinthe: The Green Goddess by Aliester Crowley; The International, 1918

absintheonline.com

thujone.info