Born to an aristocratic family on 24 November 1864, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from an unknown genetic disorder and broke both legs in his early teens; during his convalescence he turned to drawing and painting. In 1882, Lautrec moved from Albi to Paris where he studied art in the ateliers of two academic painters, Léon Bonnat and Fernand Cormon, who also taught Émile Bernard and Vincent van Gogh. Lautrec soon began painting en plein air in the manner of the Impressionists, and often posed sitters in the Montmartre garden of his neighbor, Père Forest. By 1885 he had a studio in Montmartre, the notorious center of Parisian nightlife.

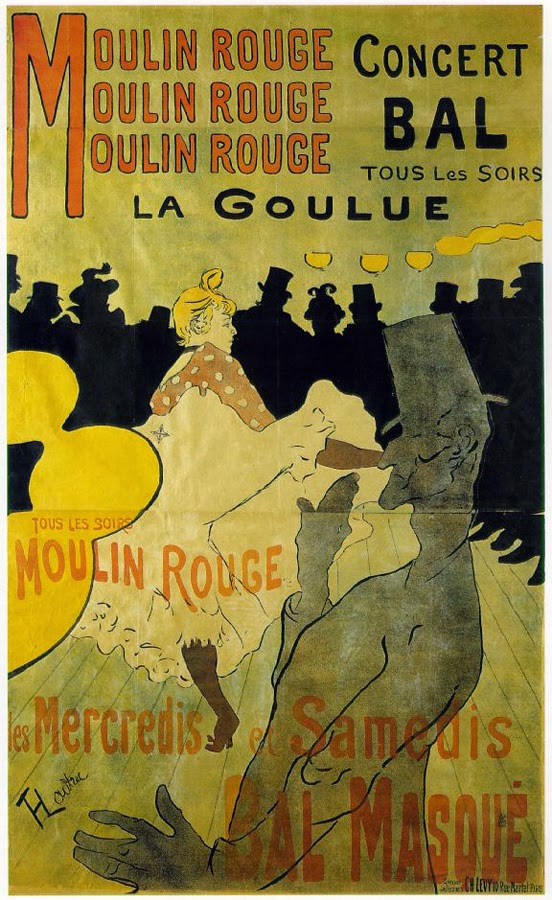

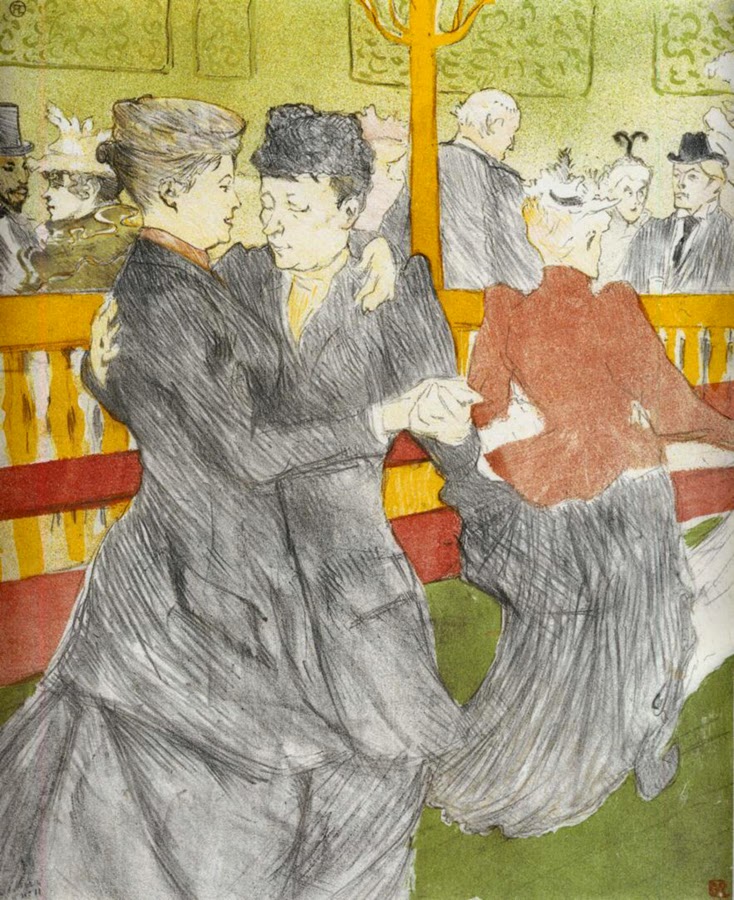

Toulouse-Lautrec regularly spent his evenings in the Montmartre cabarets; among the painter’s favorite subjects were the dancers Yvette Guilbert, La Goulue, Jane Avril and fellow artist Suzanne Valadon,. The dance halls often commissioned Lautrec to create advertising posters, dazzling lithographs filled with the vigor and movement the sickly artist must have wished he possessed. After its opening the Moulin Rouge dance hall reserved a table for Lautrec every night and displayed his paintings and sketches in the foyer.

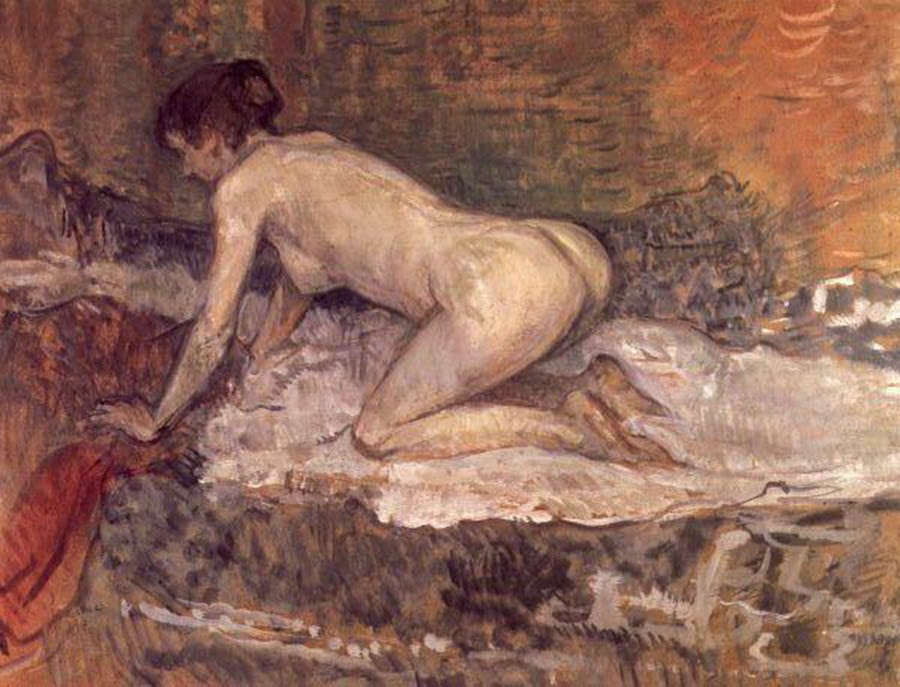

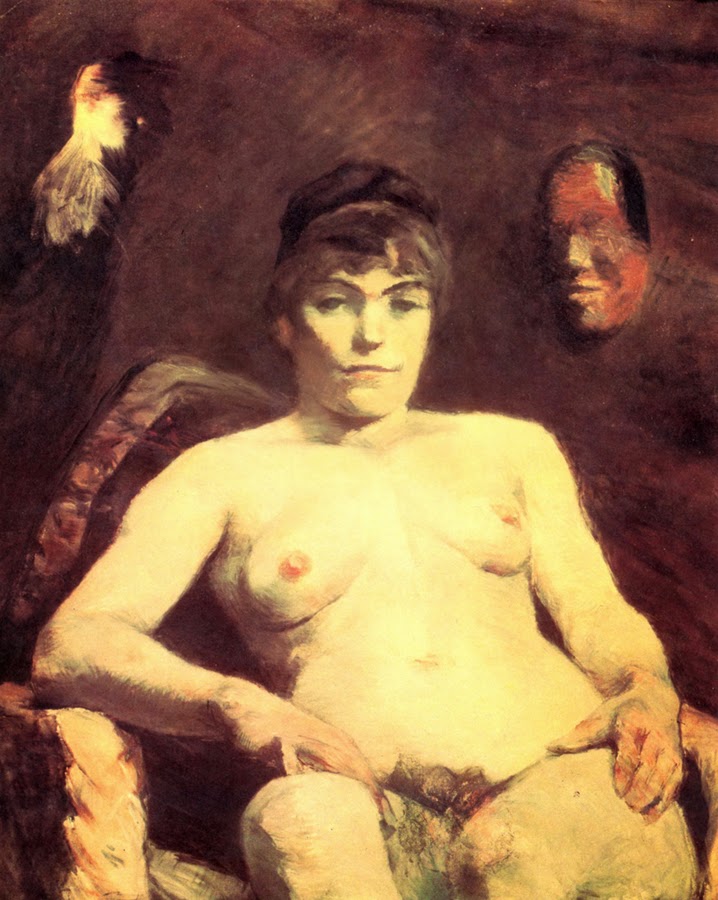

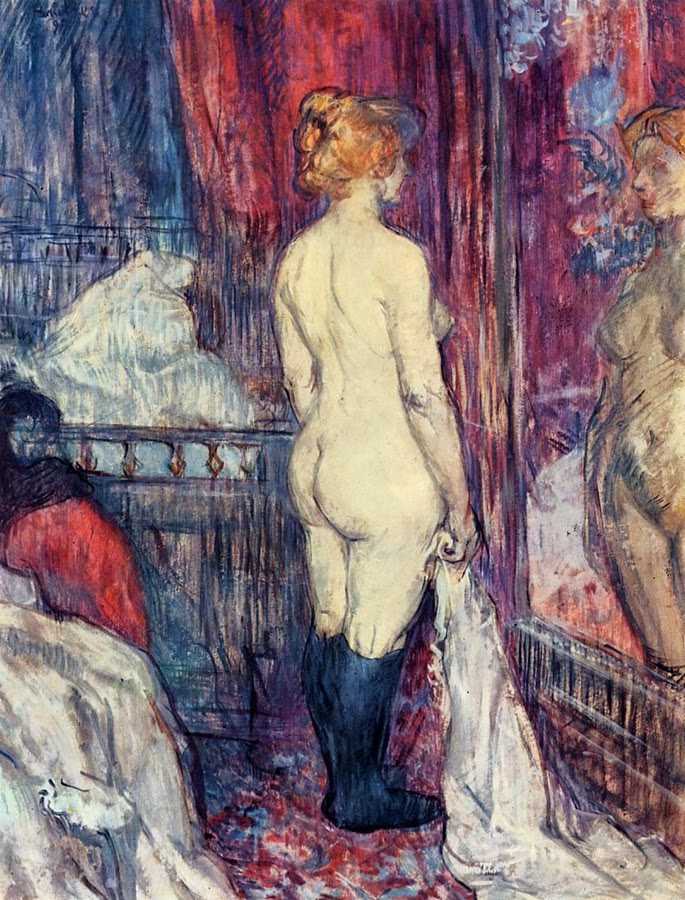

Alongside the dancers, one of his favorite models was a prostitute nicknamed La Casque d’Or (Golden Helmet), seen in the painting The Streetwalker. Lautrec used peinture à l’essence, or oil thinned with turpentine, on cardboard with loose, sketchy brushwork. The transposition of this woman of the night to the bright light of day -her pallid complexion and artificial hair color clash with the naturalistic setting-signals Lautrec’s fascination with sordid and dissolute subjects.

|

| “The Streetwalker”, La Casque d’Or |

|

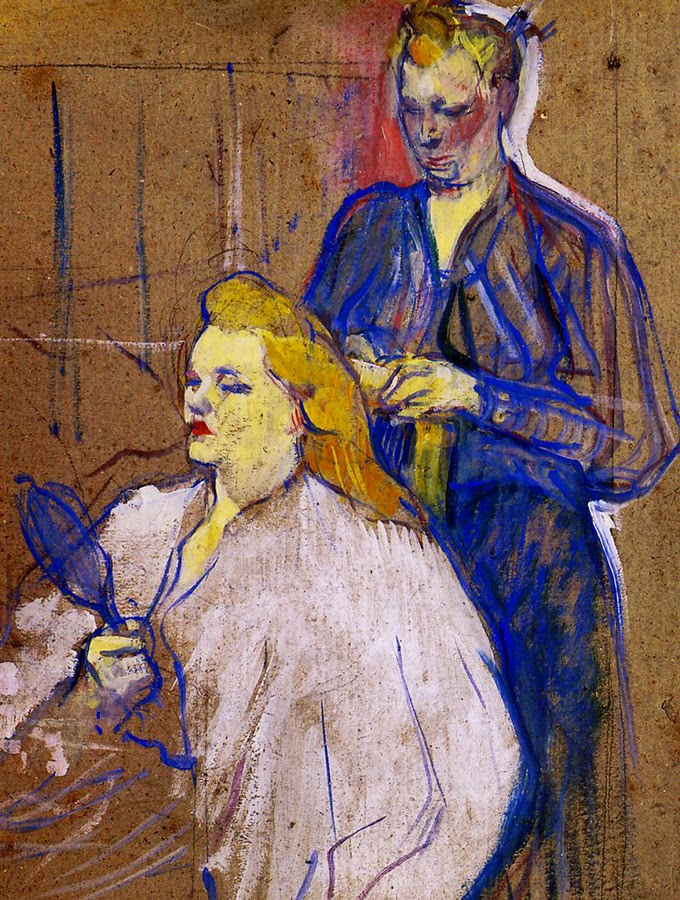

| Carmen Gaudin |

Lautrec adored redheads, especially the prostitute and laundress Carmen Gaudin, who went by the street name “Rosa la Rouge”. He first met Gaudin in 1884 while dining in Montmartre with Henri

Rachou, his friend and fellow student at Cormon’s atelier. Lautrec was fascinated both by her red hair and by the young woman’s simple and natural expression; he painted her 13 times. One of these was presented in Brussels in 1888 on the occasion of an exhibition of the group “Vingt”.

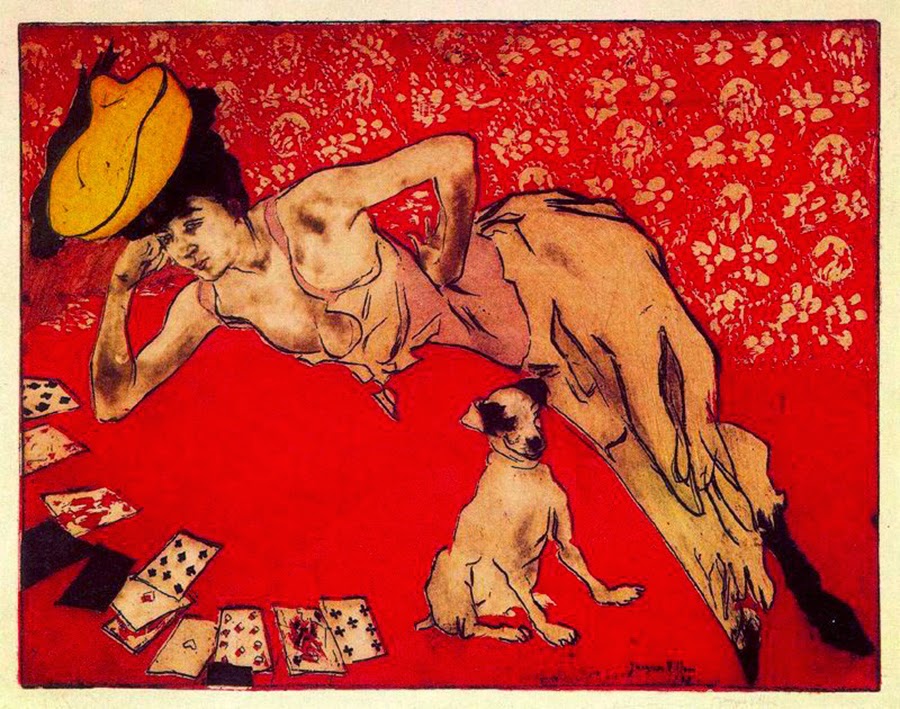

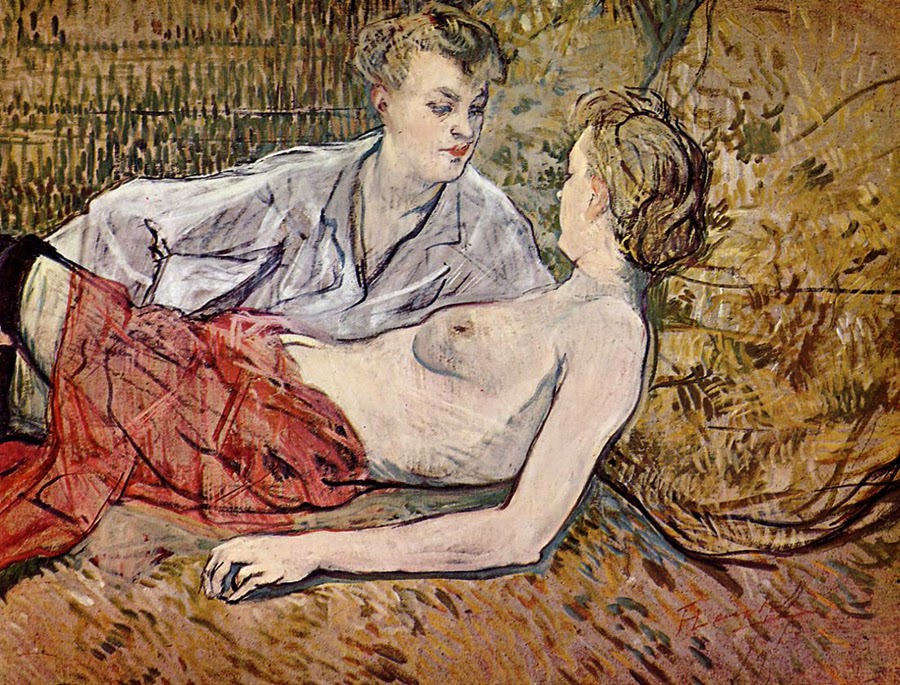

Late nineteenth-century France was a world where the men and women of high society did not publicly mix with those of lower standing; yet the business of prostitution, in which rich men sought pleasure in the daughters of the poor, was legal and accepted. Toulouse-Lautrec believed art should reach audiences beyond the bourgeois collectors and frequently contributed newspaper illustrations to achieve this end. His paintings and prints often depict the “fallen” women of society with honesty and beauty, while his aristocratic models appear grotesque in their affectations. Though not images of classic beauty, his depictions of Parisian prostitutes embrace the richness and poignancy of unique human personalities.

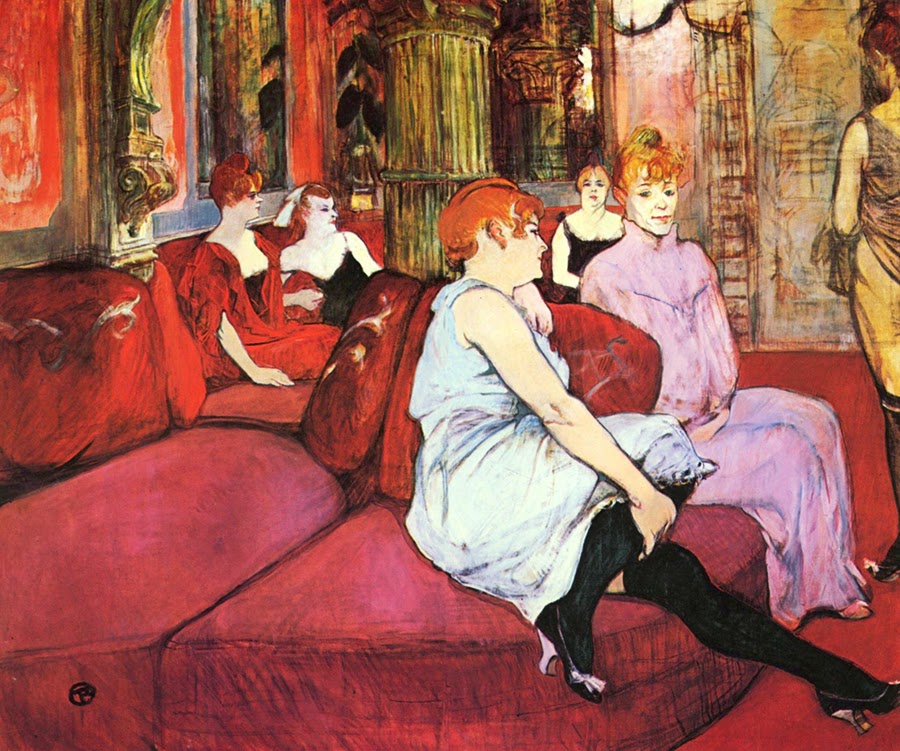

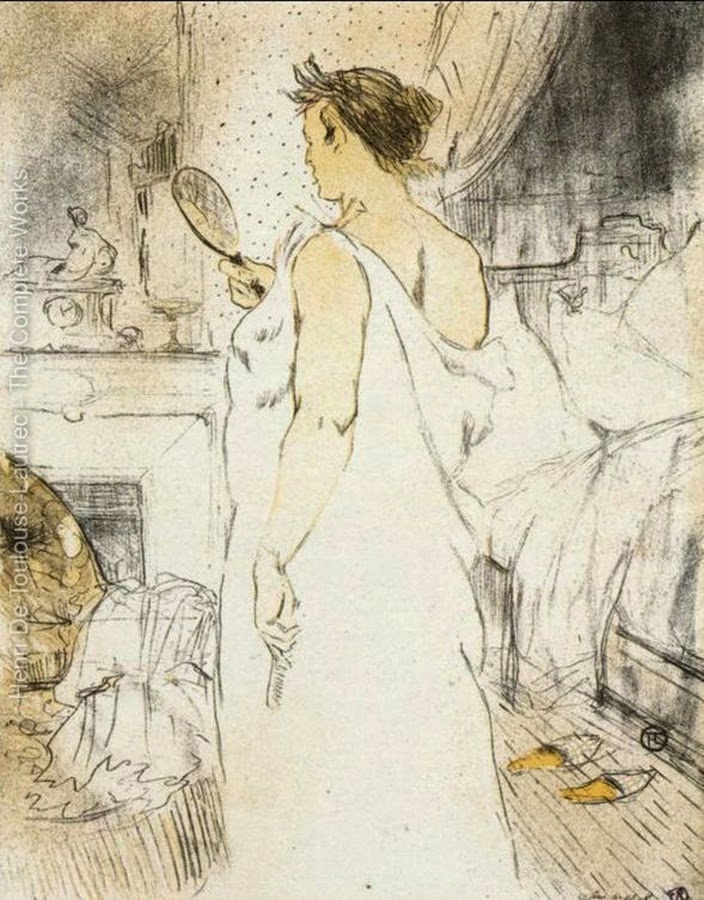

In the brothels many artists found a source of female models, and Toulouse-Lautrec soon became known and liked among the girls. Uninterested in shock value, Toulouse-Lautrec avoided painting sexual encounters; instead he observed and recorded the prostitute’s day to day life as honestly as possible.

At times he would pack up and move into a brothel for days or months on end. Bidding farewell to his friends as if for a long journey, he would proceed a few hundred yards down the street to the houses of the Rue de Richelieu or the Rue des Moulins and set up his studio. He reportedly enjoyed shocking new acquaintances by giving the address of these brothels as his place of residence, but prostitutes and madams accepted Lautrec as a fellow outcast and permitted him to wander about, sketching and painting freely, often on commission to the house itself.

He shared the lives of the women who made him their confidant, painting and drawing them at work and at leisure and neither vilifying nor glamorizing them, but presenting an objective, almost documentary view of the everyday life they shared with him.

Lautrec’s representations of the world of prostitution evidence a real sympathy for the women; but the works are still dominated by a matter-of-fact mentality. The women are shown awaiting clients, submitting to medical exams, lying on beds, and embracing. In the Salon: The Sofa he illustrates a group of prostitutes in a maison close seated upon a red divan, awaiting their clients. With resigned faces and tired eyes, modestly cut frocks, and reserved body language, these women engage with neither the viewer nor one another, embodying a world of alienation. Alternately compassionate and voyeuristic, his brothel scenes are some of his most complex works.

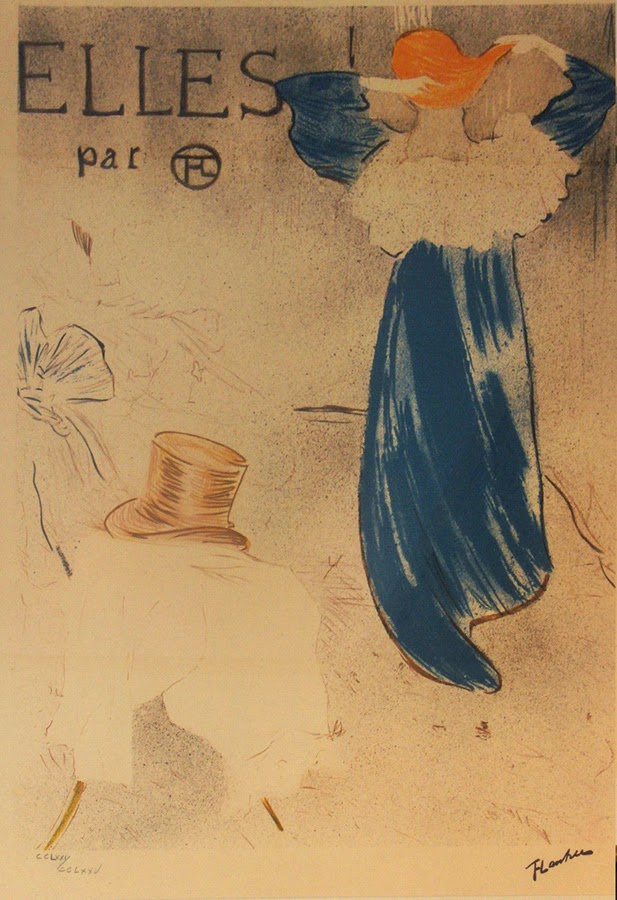

Between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s Lautrec produced some 50 paintings on the theme of prostitution, none of which was publicly exhibited during his lifetime. Only Elles, his 1896 album of 11 color lithographs that depicts the daily routines of prostitutes, was published. Most of these pieces are breezily attuned to the atmosphere in these establishments – light, brightly colored and so loosely drawn they are almost sketches. He painted quickly, frequently in thinned oil paint on unprimed cardboard, using its neutral tone as a design element and conveying action and atmosphere in a few economical strokes. Japanese prints inspired his oblique angles of vision, near-abstract shapes, and calligraphic lines. In later years graphic works took precedence; his paintings were often studies for lithographs. But Toulouse-Lautrec was also capable of producing superbly detailed oil paintings of great depth.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris from 1889: in 1891 his first posters brought him immediate recognition. But Lautrec was mocked for his short stature and physical appearance, which led him to drown his sorrows in alcohol. At first this was beer and wine, but his tastes expanded; one of first notable Parisians who enjoyed American-style cocktails, he had parties at his house on Friday nights and forced his guests to try them. The invention of the cocktail “Earthquake” or Tremblement de Terre is attributed to Toulouse-Lautrec: a potent mixture containing half absinthe and half cognac (in a wine goblet, 3 parts Absinthe and 3 parts Cognac, sometimes served with ice cubes or shaken in a cocktail shaker filled with ice). He even had a cane that hid alcohol so that a drink was always available.

In 1893 Lautrec’s alcoholism began to take its toll, and as those around him realized the seriousness of his condition there were rumors of a syphilis infection, possibly contracted from his prostitute lover Carmen Gaudin. In 1899 his mother and some concerned friends had him briefly institutionalized.

He died from complications due to alcoholism and syphilis at the family estate in Malromé at the age of 36. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is buried in Verdelais, Gironde, a few kilometres from the Château Malromé, where he died. After Lautrec’s death, his mother, the Comtesse Adèle Toulouse-Lautrec along with his art dealer Maurice Joyant heavily promoted his work. His mother contributed funds for a museum to be created in Albi, his birthplace: The Toulouse-Lautrec Museum owns the world’s largest collection of works by the painter.

Today is the 150th anniversary of his birth.

References and More:

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Foundation

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – MOMA

The Sun Between the Storms; Part III, Paris