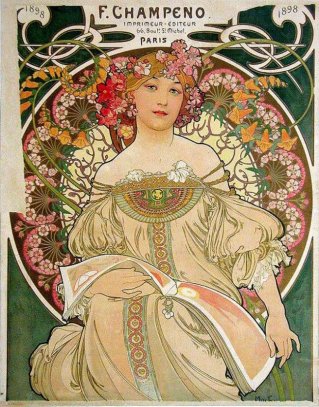

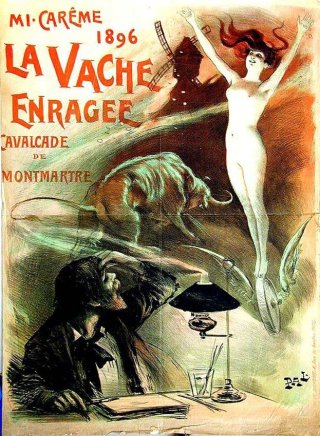

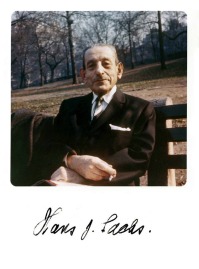

Hans Josef Sachs was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland) in 1881; he began collecting posters when he was only 16, possibly inspired by three life-size prints of Sarah Bernhardt signed by Alphonse Mucha which were presented as a gift to his father.

Hans Josef Sachs was born in Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland) in 1881; he began collecting posters when he was only 16, possibly inspired by three life-size prints of Sarah Bernhardt signed by Alphonse Mucha which were presented as a gift to his father.

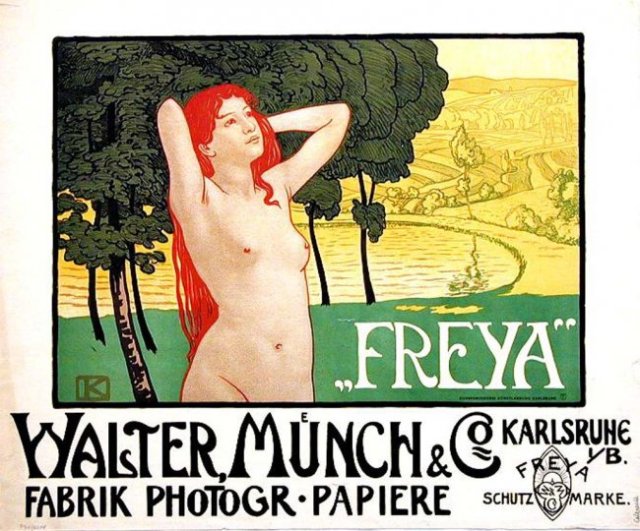

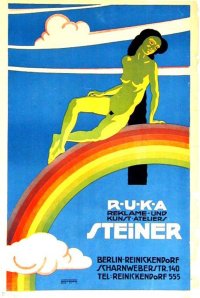

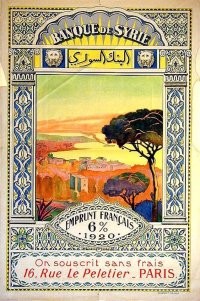

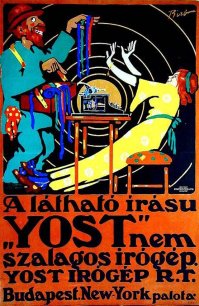

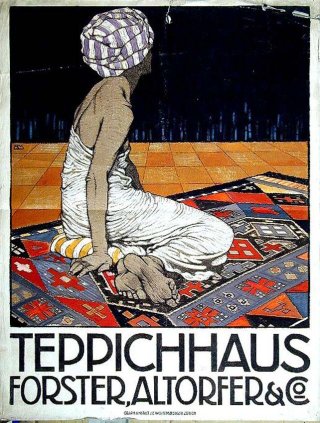

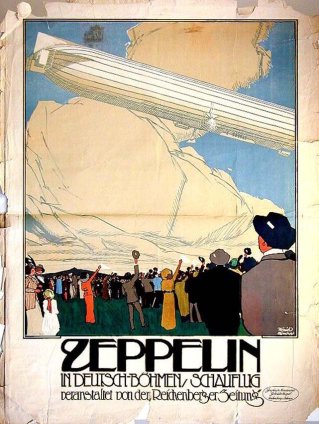

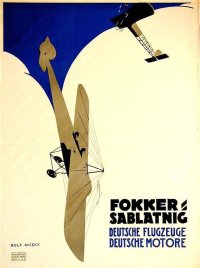

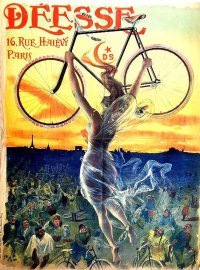

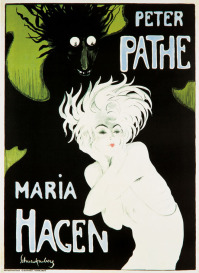

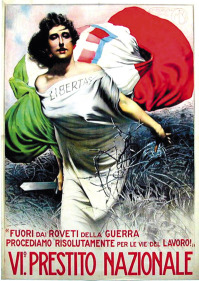

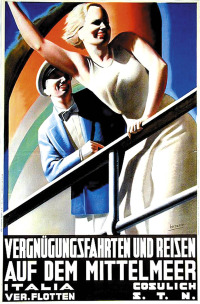

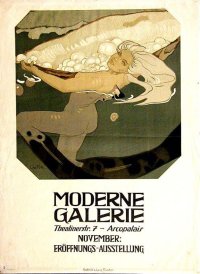

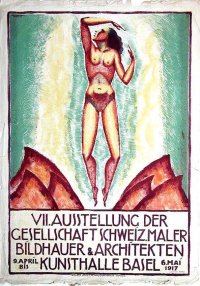

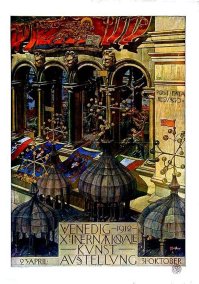

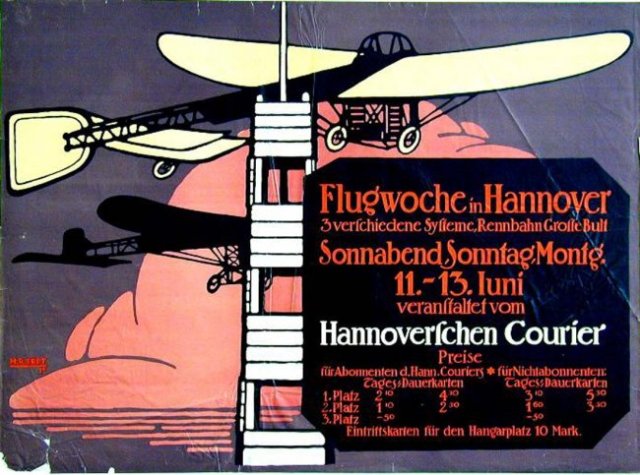

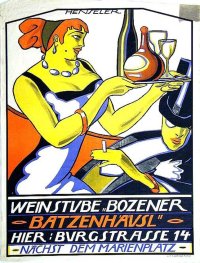

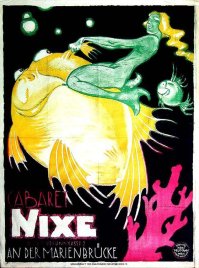

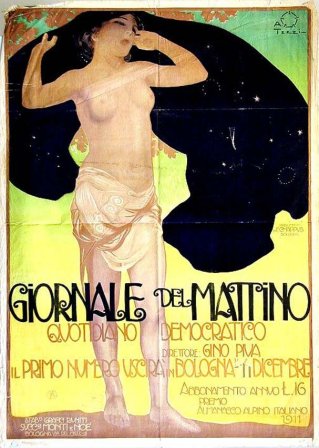

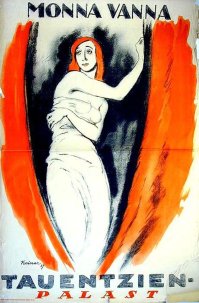

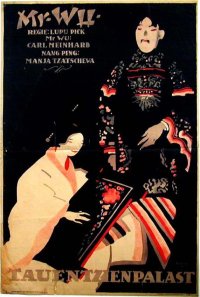

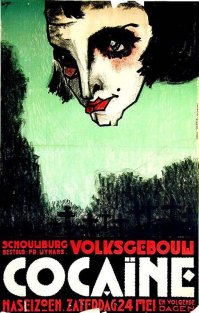

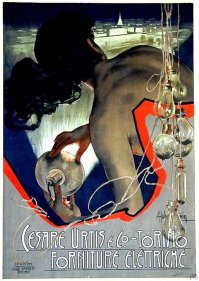

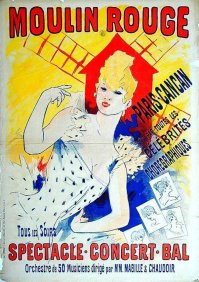

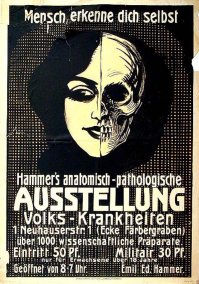

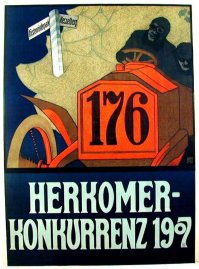

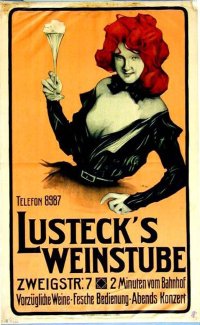

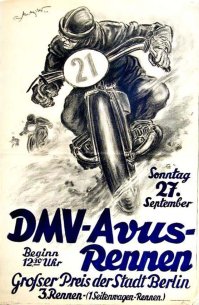

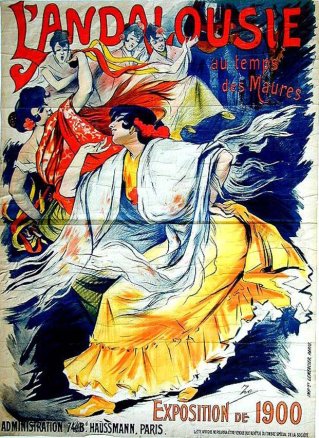

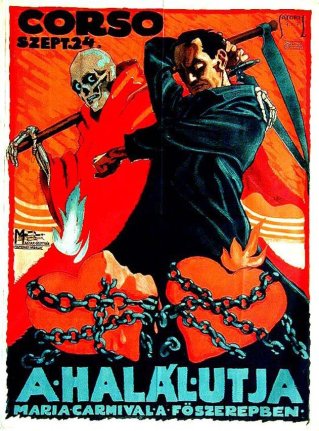

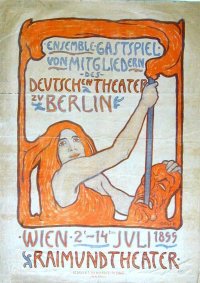

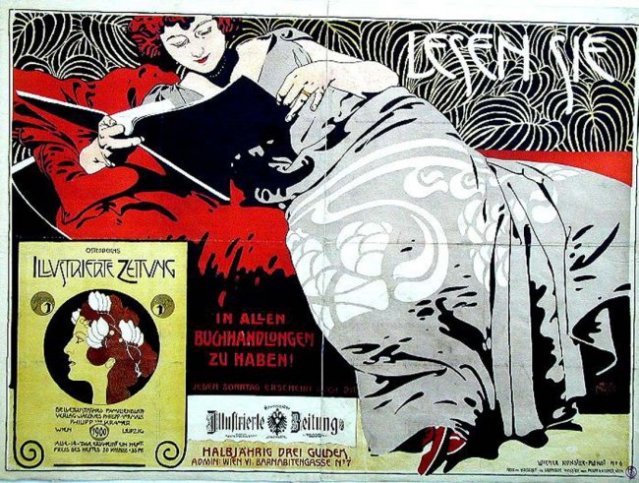

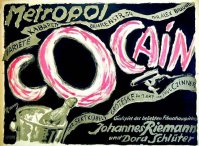

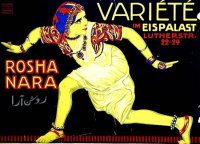

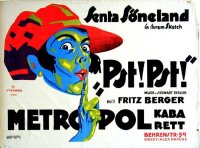

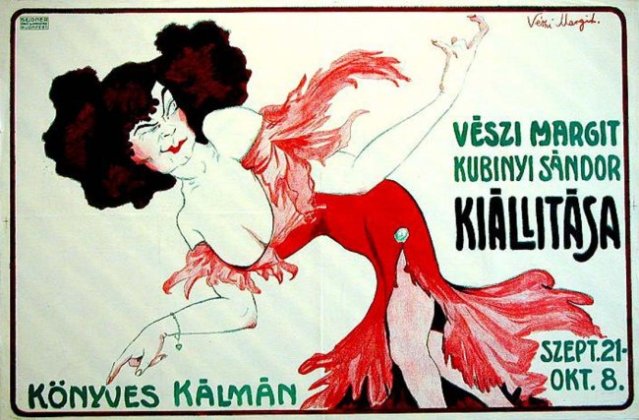

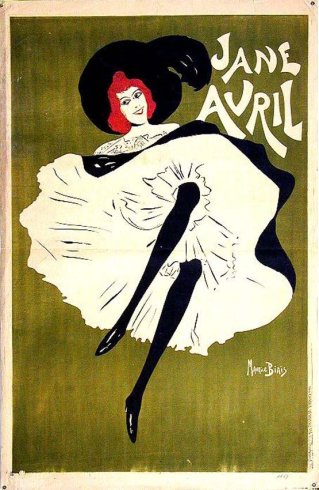

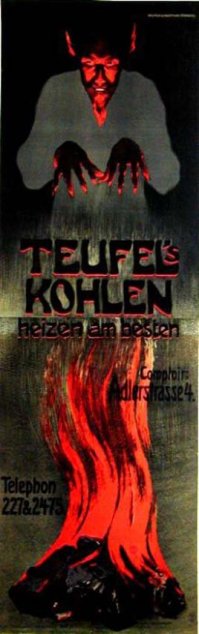

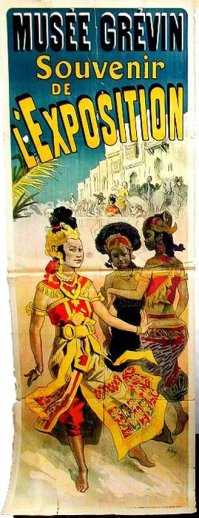

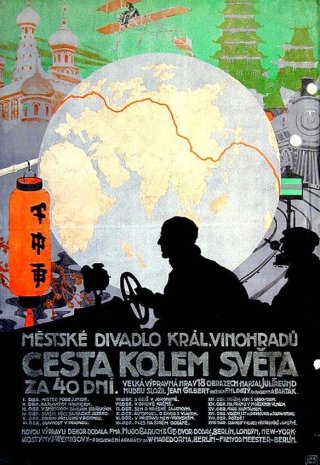

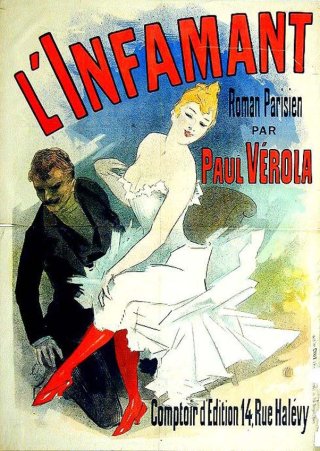

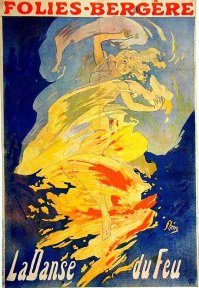

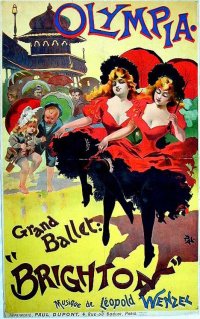

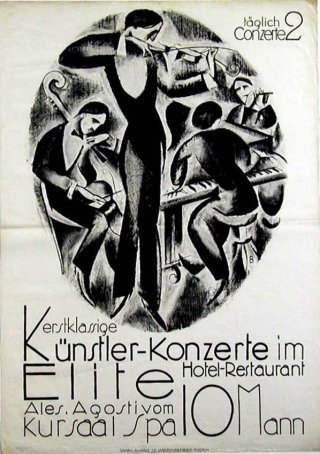

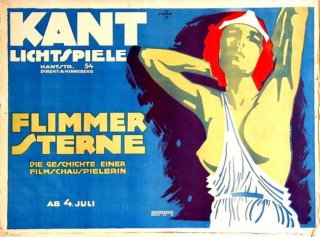

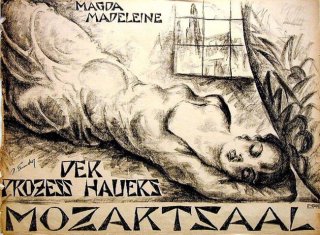

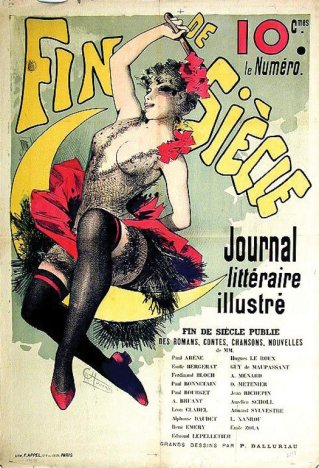

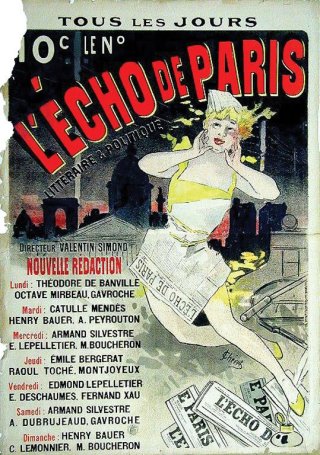

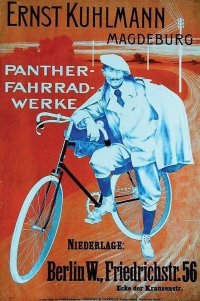

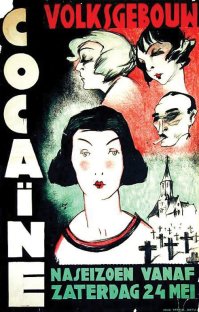

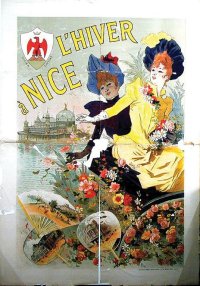

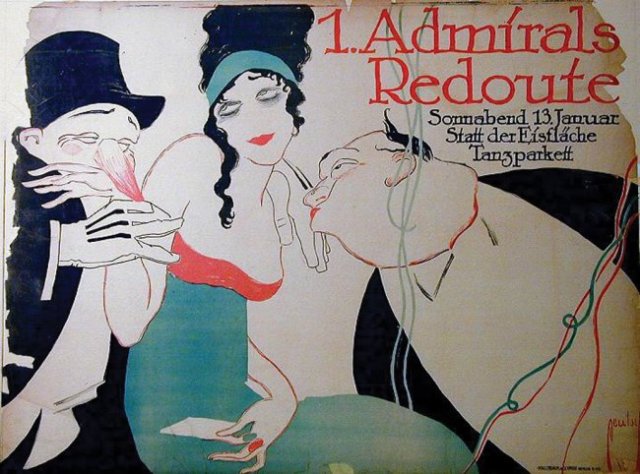

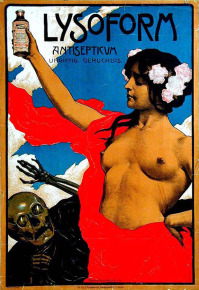

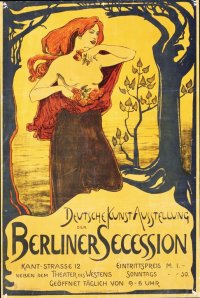

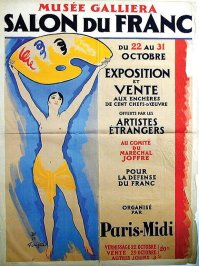

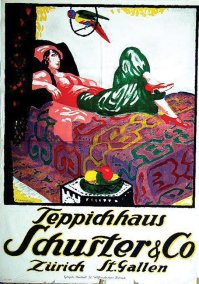

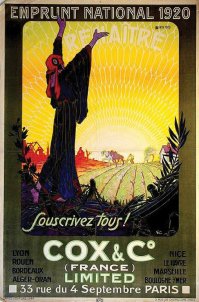

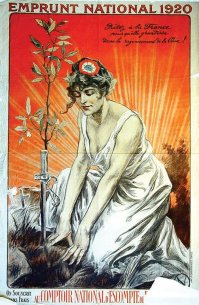

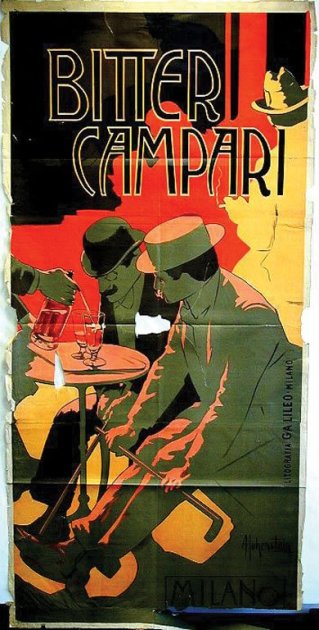

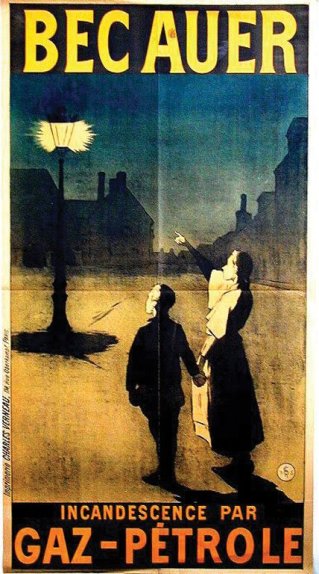

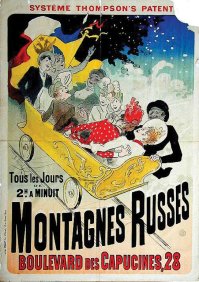

Sachs received his doctorate in 1904 in chemistry, physics, and mathematics, then another in dentistry. While he was successful as a dentist -Albert Einstein was among his patients- his avocation was posters. He regularly worked from three o’clock in the afternoon into the night on his passion, making a detailed index card for each poster, each of which was identified by a numbered label. His collection grew rapidly, but was not narrowly focused; the 12,500 pieces included works by world-famous artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Wassily Kandinsky, Käthe Kollwitz and Edvard Munch as well as 31 of the 35 posters designed by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. By the time he was 24 years old in 1905, Hans Sachs had the largest private collection of posters in Germany.

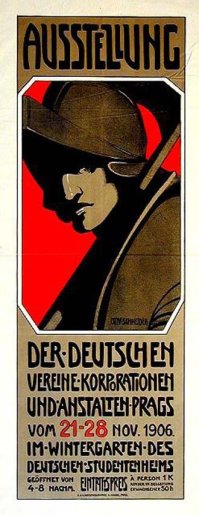

In 1905 Sachs became one of the principal founders of the Verein der Plakatfreunde (Society of Poster Friends), which soon opened regional chapters. In 1910 it founded a quarterly Das Plakat (The Poster), with Sachs as both editor and publisher.

The purpose of Das Plakat was to promote poster art for both collectors and scholars. While there were a number of magazines devoted to posters, it was said “… the clarion of this German poster exuberance was a magazine called Das Plakat, which not only exhibited the finest poster examples from Germany and other European countries, but its high standards underscored its exquisite printing, established qualitative criteria that defined the decade of graphic design between 1910 and 1920.” During its short life from 1910 to 1921, its circulation grew from 200 to over 10,000.

After an attic fire that threatened but thankfully did not damage his collection, Sachs began to work on finding a way to display the posters so that the public could see them. In 1926 he had an addition built to house his collection. He dubbed it the Museum of Applied Arts and opened it to the public.

On Kristallnacht, 9 November 1938, Hans Sachs was arrested and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The collection was stolen by order of Josef Goebbels, who wanted them for a proposed new wing devoted to business art in the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin (Museum of Decorative Arts). After 17 days in the concentration camp Sachs was released, and with his second wife Felicia and their one-year-old son Peter were able to escape from Germany; first to London for a few days, and then to New York. From his former collection he was able to take with him only the 31 posters by Toulouse-Lautrec, which he later sold in America.

In the 1950s, Sachs was told by the West German government that the posters had been destroyed by the Russians, and in 1961 he accepted compensation of about 225,000 marks. But in 1966, many were rediscovered in the basement of the Deutsches Historisches Museum in East Berlin and were identified by his label affixed to the back. Although Sachs flew to Berlin in 1974, he was not allowed to enter East Berlin.

Hans Josef Sachs died in 1974 never having laid eyes on his collection again. After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the poster collection, now mysteriously reduced to fewer than 5,000 pieces, was transferred to the German Historical Museum in Berlin where it remained mainly in storage, with just a handful of posters on display at any given time.

Hans’ son Peter had no idea the collection still existed until 2005. As soon as he found out, he tried to get it back. He offered to repay the 1961 compensation at their 2005 value of 600,000 euros, but the estimated market value of the posters had skyrocketed well into the millions (it’s assessed at $6 – $21 million now), and the museum did not want to lose such an irreplaceable and important collection. He took the case before the Advisory Committee for the Return of Nazi-confiscated Art in 2007, but since the government had paid reparations, the letter of the law was not on his side.

Hans’ son Peter had no idea the collection still existed until 2005. As soon as he found out, he tried to get it back. He offered to repay the 1961 compensation at their 2005 value of 600,000 euros, but the estimated market value of the posters had skyrocketed well into the millions (it’s assessed at $6 – $21 million now), and the museum did not want to lose such an irreplaceable and important collection. He took the case before the Advisory Committee for the Return of Nazi-confiscated Art in 2007, but since the government had paid reparations, the letter of the law was not on his side.

Peter Sachs then took the case to district court, but in 2009 they agreed with the decision of the Advisory Committee. He kept appealing to higher courts, until eventually the Federal Court of Justice ruled that Peter Sachs is the rightful owner of his father’s poster collection.

The decision notes that although Peter did not file for restitution by the deadline and although his father had received legal compensation, for the posters not to be returned “would perpetuate Nazi injustice.” Since the intent of restitution laws was to reinstate the property rights stripped from the victims of Nazi terror, keeping the posters would contravene the entire point of the law. Hans Sachs’s son Peter was ruled to be the lawful owner of 4344 posters, but the museum held the collection for another 4 years.

In January 2013 roughly 3,700 of the posters began going up for auction through New York’s Guernsey’s auction house. Many of the others were gifted to or purchased by museums.

Peter Sachs died on September, 2013.

References:

hyperallergic.com – article on the Sachs auctions

The Hans Sachs poster collection auction, day 1

The Hans Sachs poster collection auction, day 2

The Hans Sachs poster collection auction, day 3