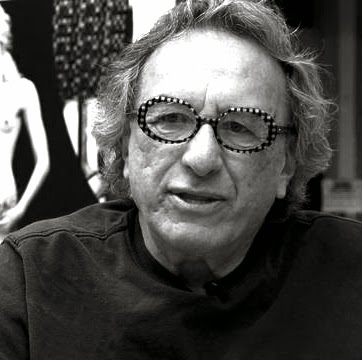

Joel-Peter Witkin

The accident involved three cars, all with families in them. Somehow, in the confusion, I was no longer holding my mother’s hand. At the place where I stood at the curb, I could see something rolling from one of the overturned cars. It stopped at the curb where I stood. It was the head of a little girl. I bent down to touch the face, to speak to it — but before I could touch it someone carried me away.”

The accident involved three cars, all with families in them. Somehow, in the confusion, I was no longer holding my mother’s hand. At the place where I stood at the curb, I could see something rolling from one of the overturned cars. It stopped at the curb where I stood. It was the head of a little girl. I bent down to touch the face, to speak to it — but before I could touch it someone carried me away.”

Brooklyn born Joel-Peter Witkin claims that his vision and sensibility were initiated by an episode he witnessed as a small child, a car accident that occurred in front of his house in which a little girl was decapitated: ”

He worked as a war photographer between 1961 and 1964 during the Vietnam war. In 1967, he decided to work as a freelance photographer and became the official photographer for City Walls Inc.; later he studied

sculpture at Cooper Union in New York where he received his Bachelor of Arts in 1974. He holds a MFA from the University of New Mexico, and continues to work in Albuquerque.

Witkin’s parents were reportedly unable to transcend their religious differences and divorced when he was young: he claims the difficulties in his family as an influence for his work, combining them with references to paintings from Picasso, Balthus, Goya, Velásquez and Miro among others. Speaking of his Father, Witkin says: “He took me aside and showed me some clips from Life magazine or Look magazine, the Daily Mirror, or the News (he wasn’t a New York Times reader). I was about five, and I knew when he was showing me these photographs that he was telling me he couldn’t do this, but maybe there was a chance that part of him could, somehow, through me. Without saying it, I looked at him, and I knew, and he knew, that I could try.

I think that what makes a photograph so powerful is the fact that, as opposed to other forms, like video or motion pictures, it is about stillness. I think the reason a person becomes a photographer is because they want to take it all and compress it into one particular stillness. When you really want to say something to someone, you grab them, you hold them, you embrace them. That’s what happens in this still form.”

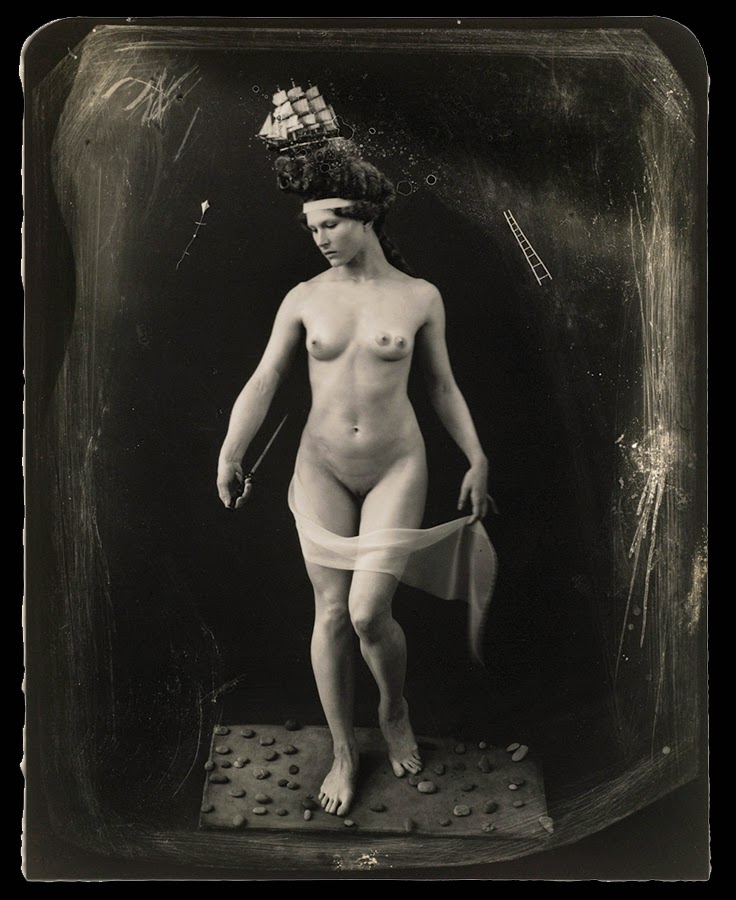

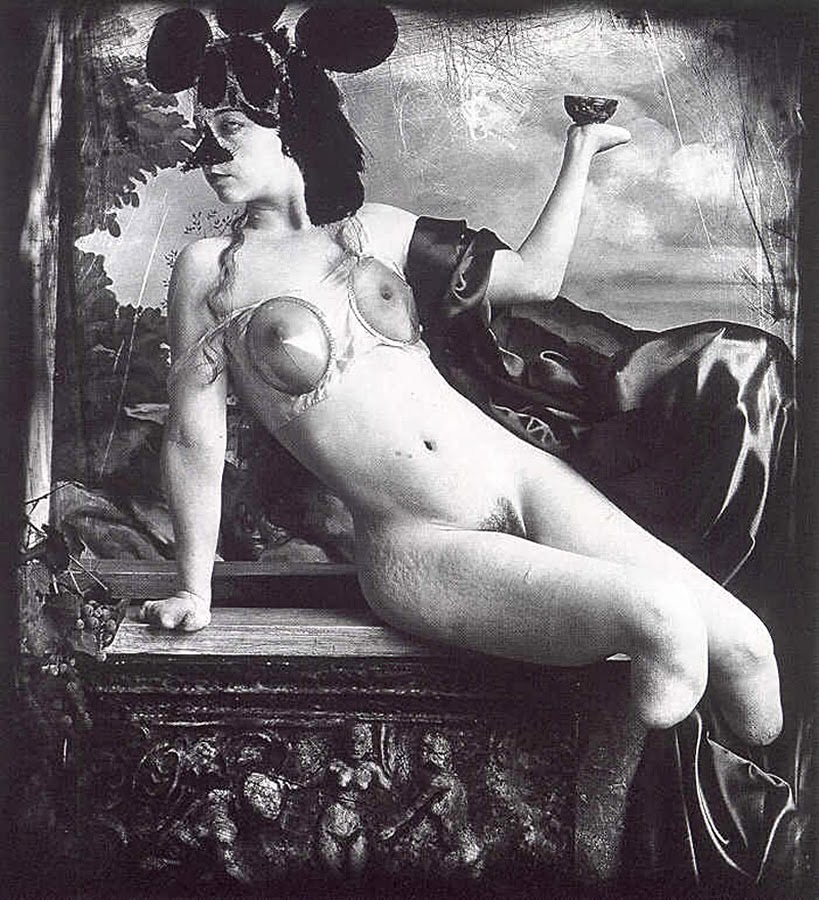

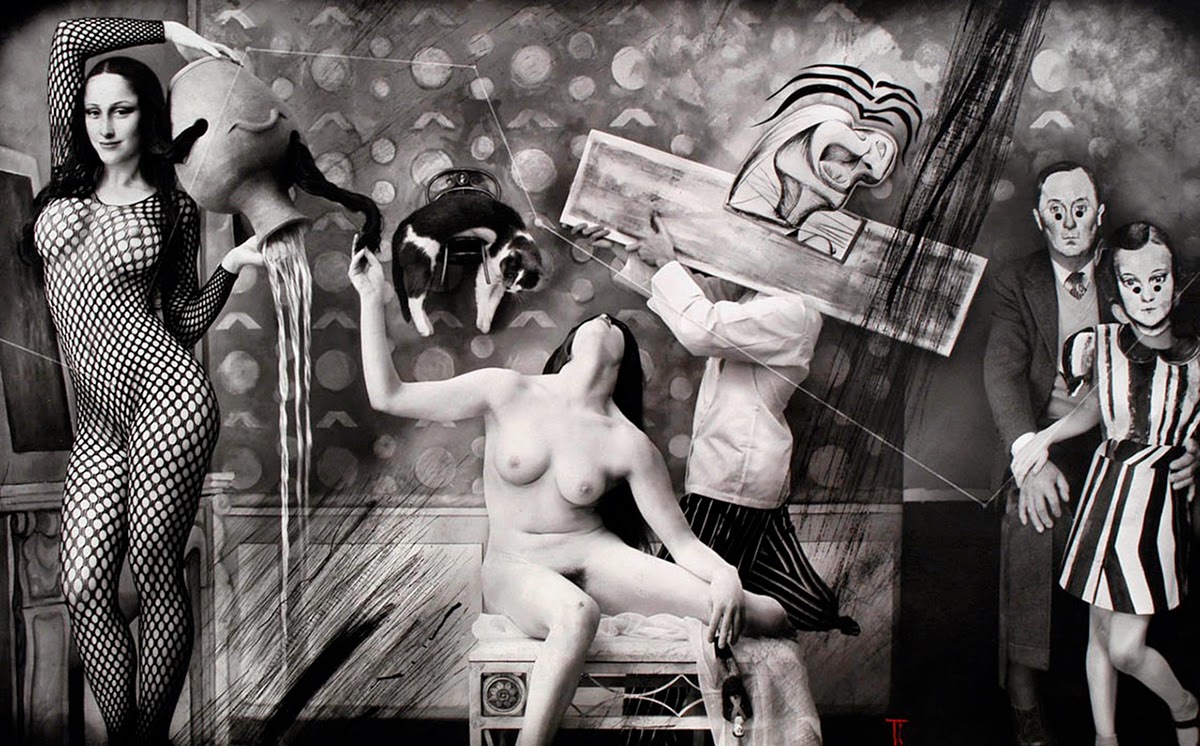

By using imagery and symbols from the past, Witkin celebrates our history while constantly

redefining its present day context.

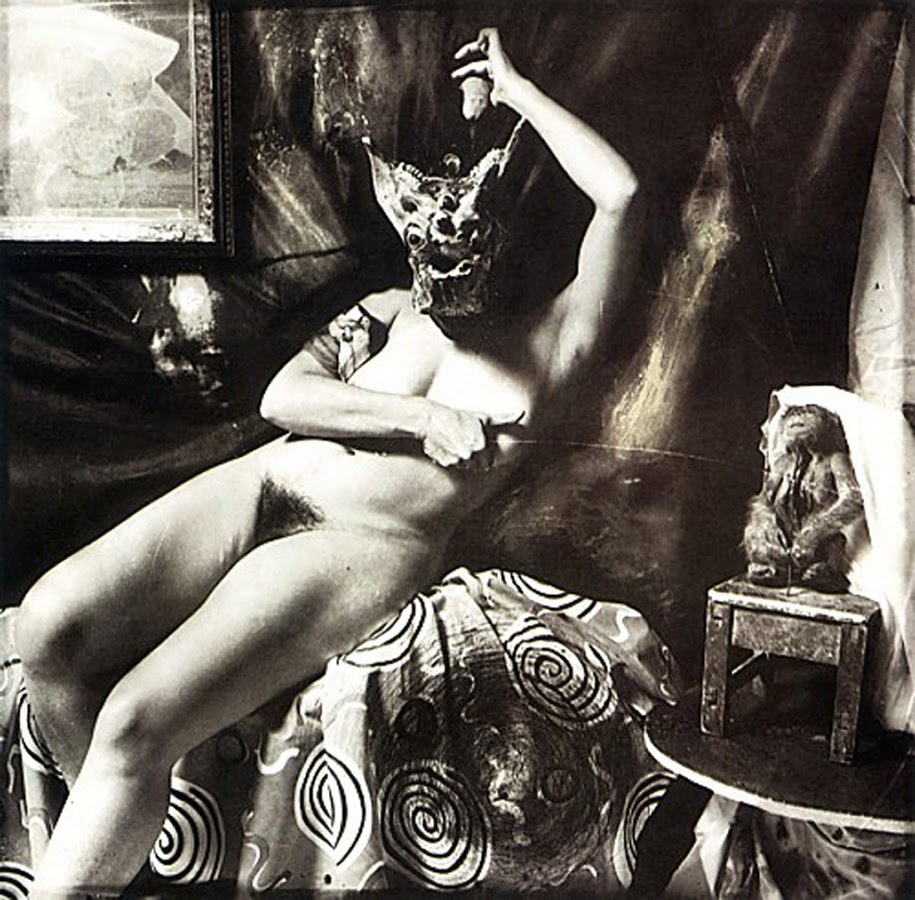

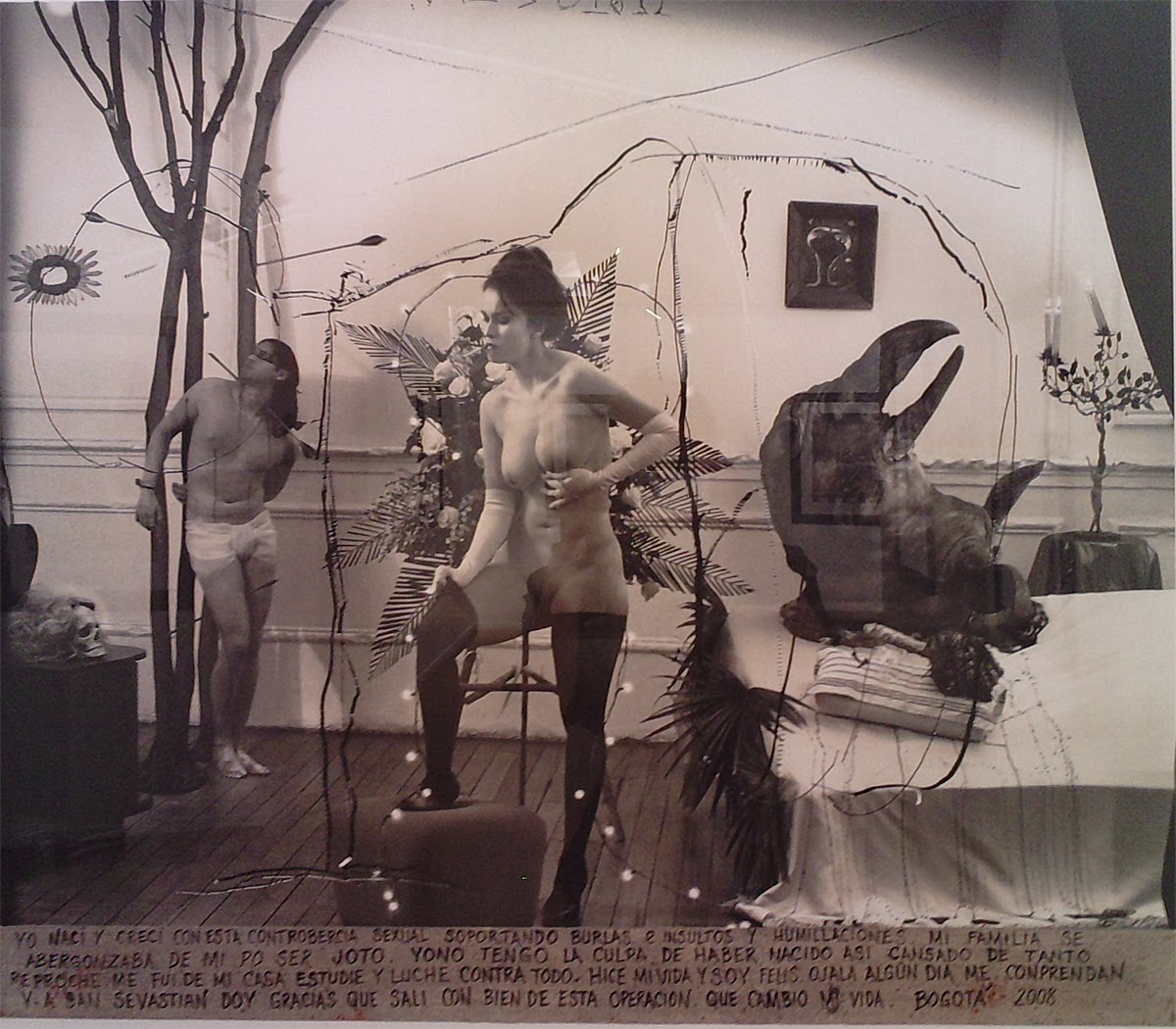

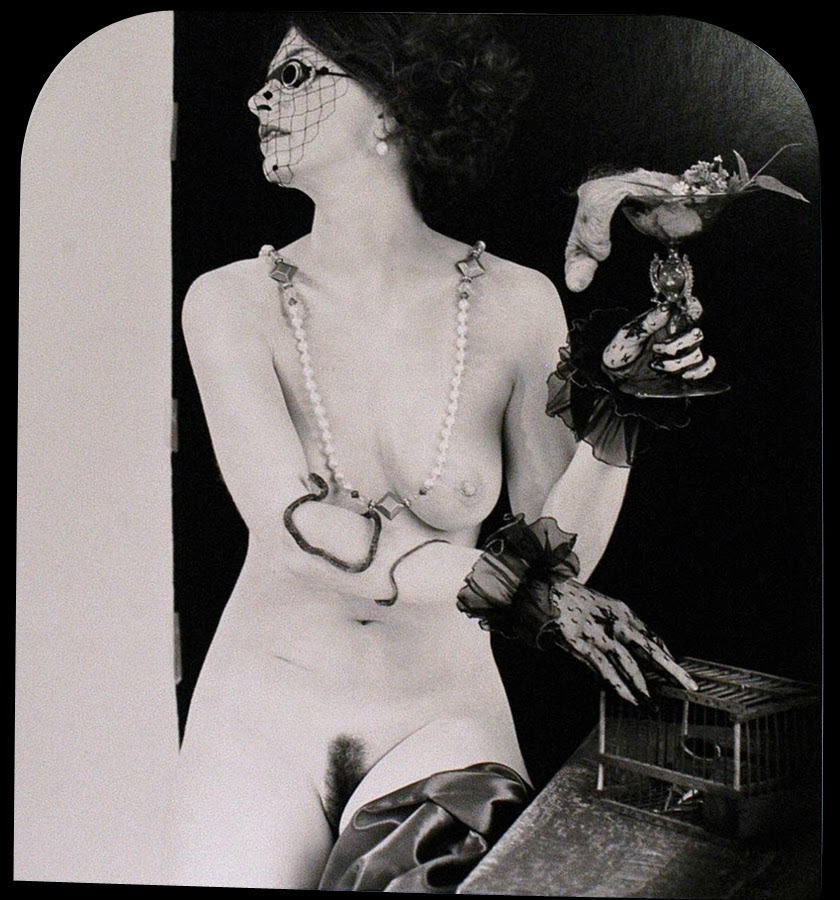

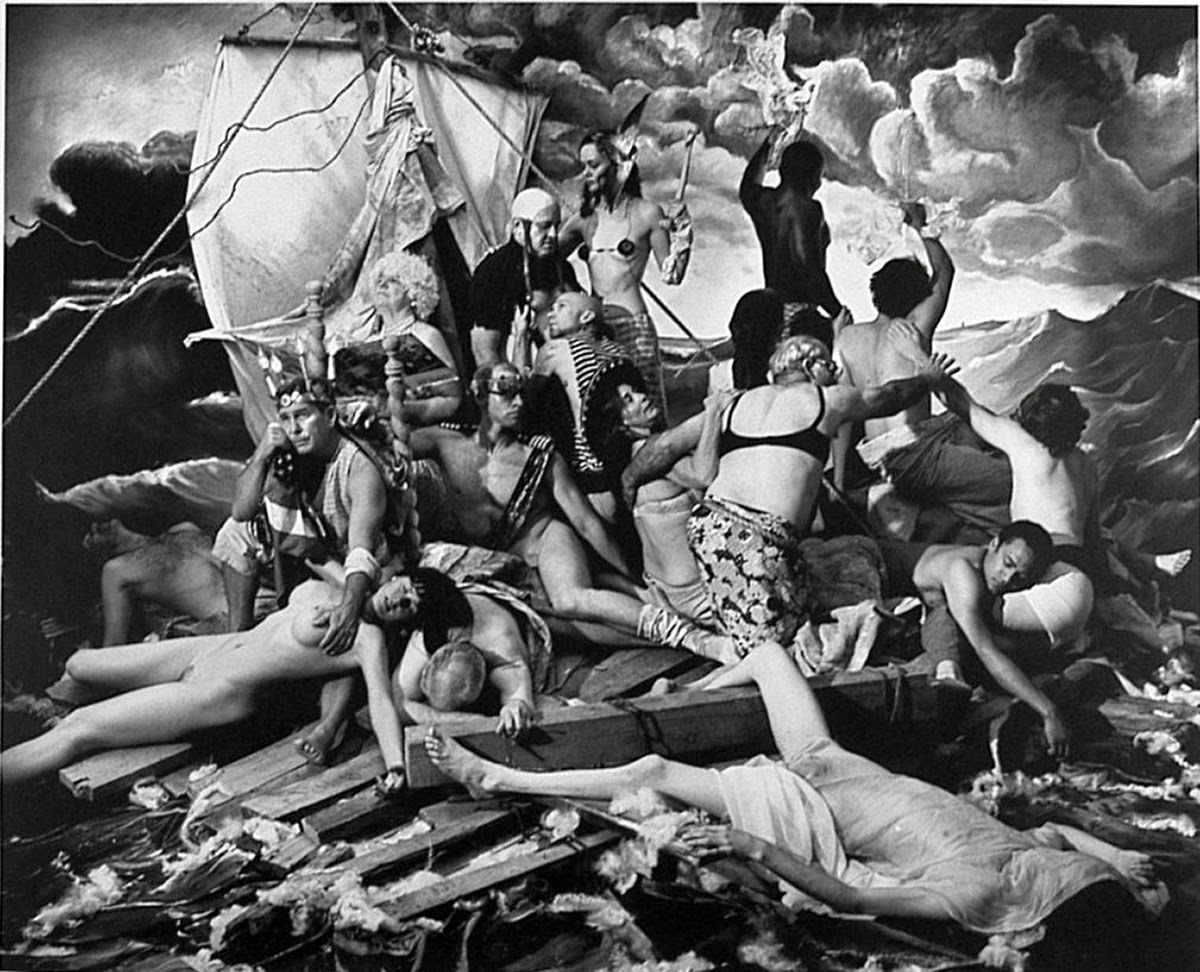

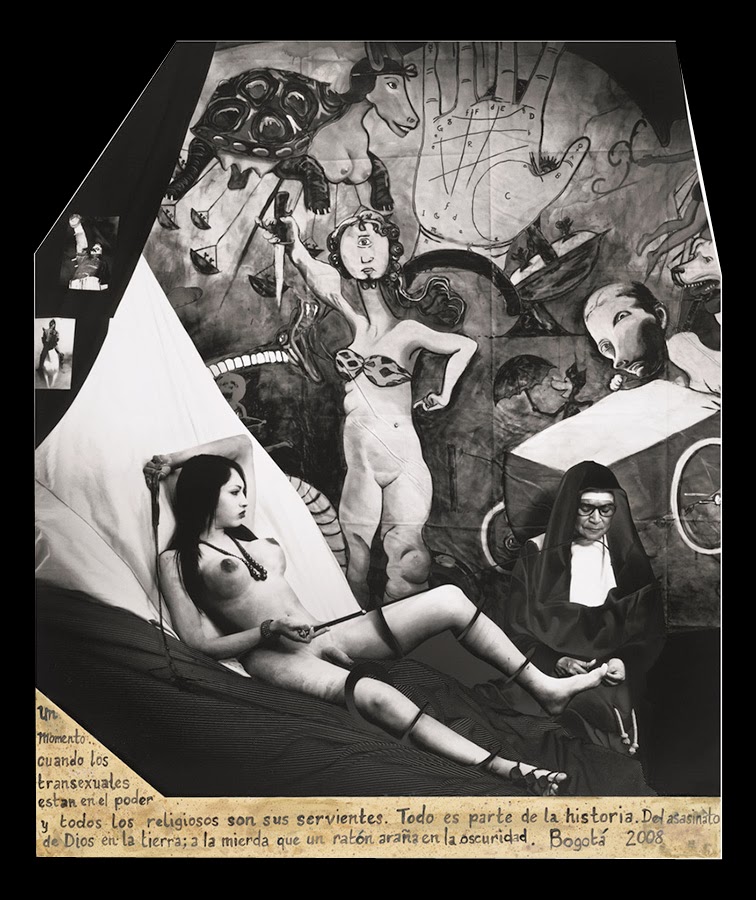

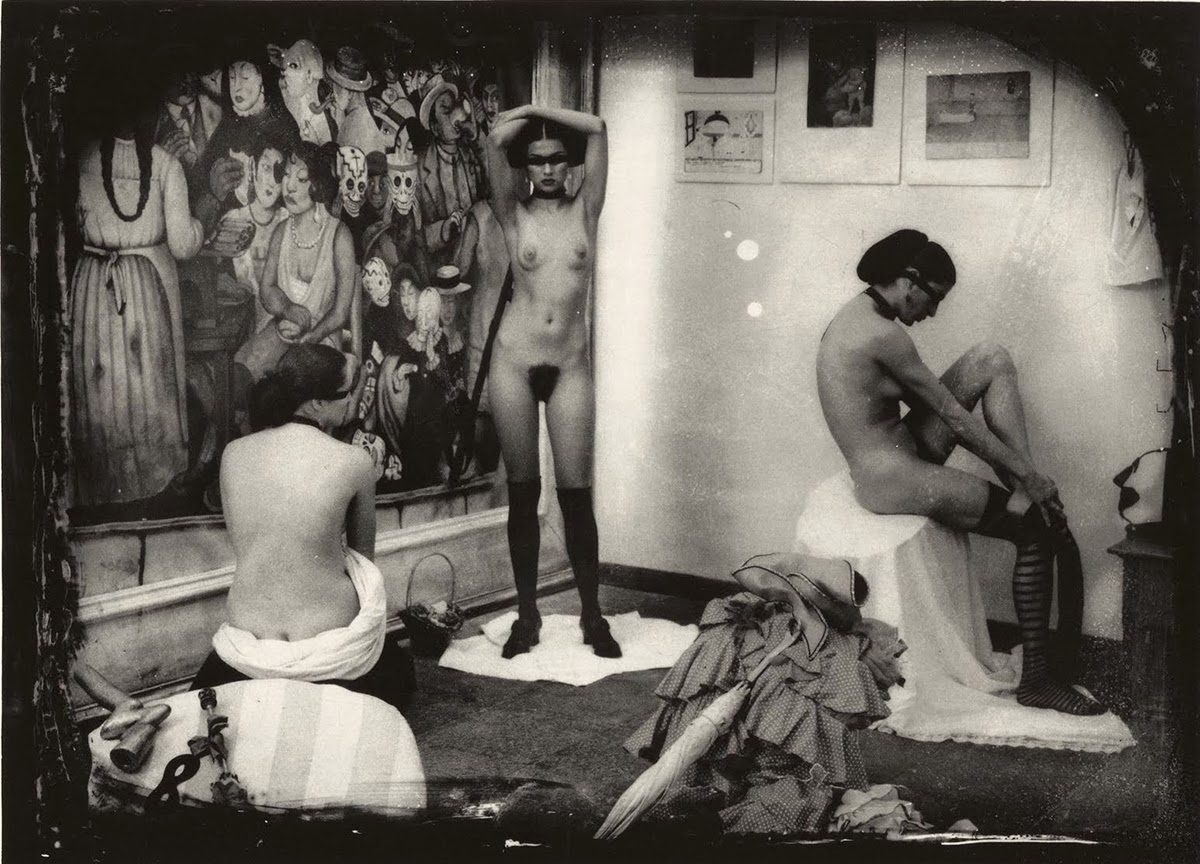

Witkin’s work is undeniably powerful. For more than forty years he has pursued his interest in spirituality and how it impacts the physical world in which we exist. Finding beauty within the grotesque, Witkin pursues this complex issue through people most often cast aside by society — human spectacles including hermaphrodites, dwarfs, amputees, androgynes, carcasses, people with odd physical capabilities, fetishists and “any living myth … anyone bearing the wounds of Christ.” His fascination with other people’s physicality has inspired works that confront our sense of normalcy and decency, while constantly examining the teachings handed down through Christianity.

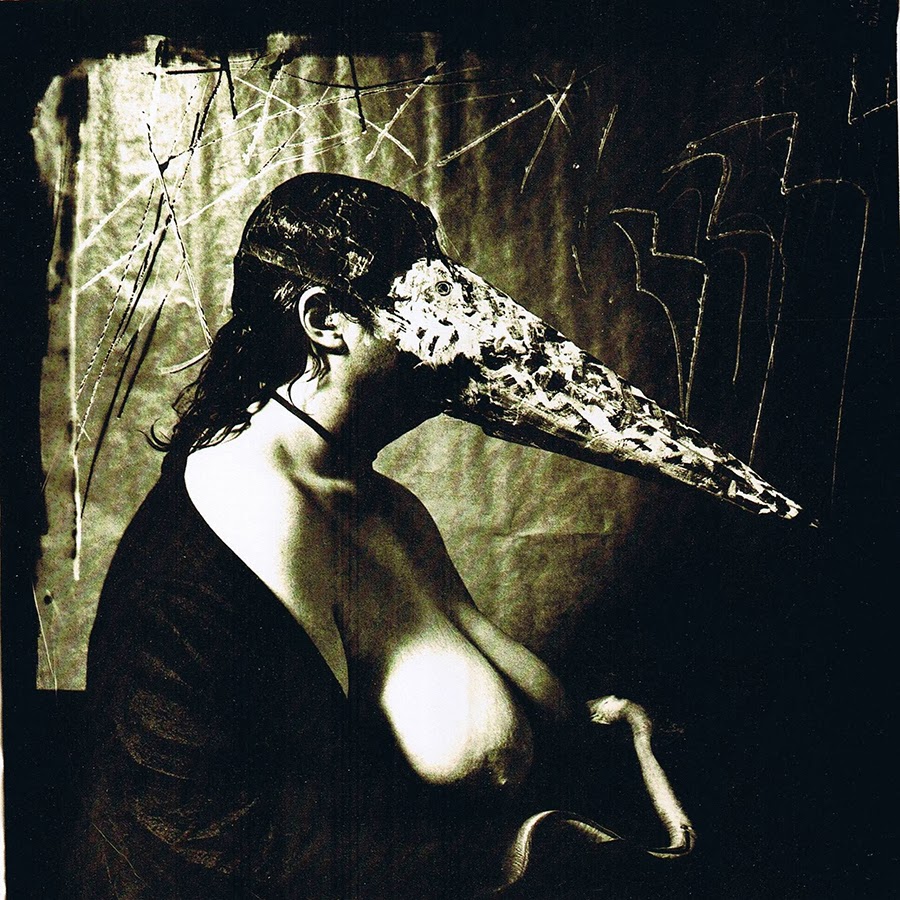

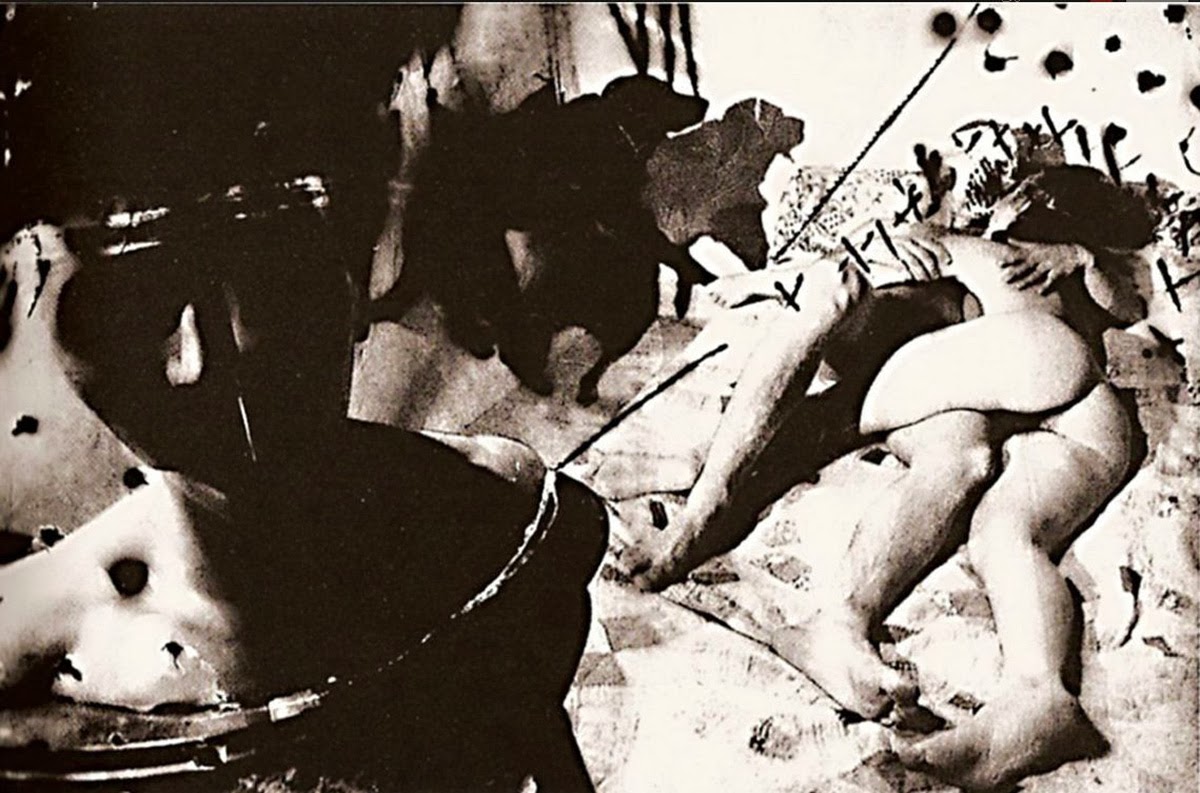

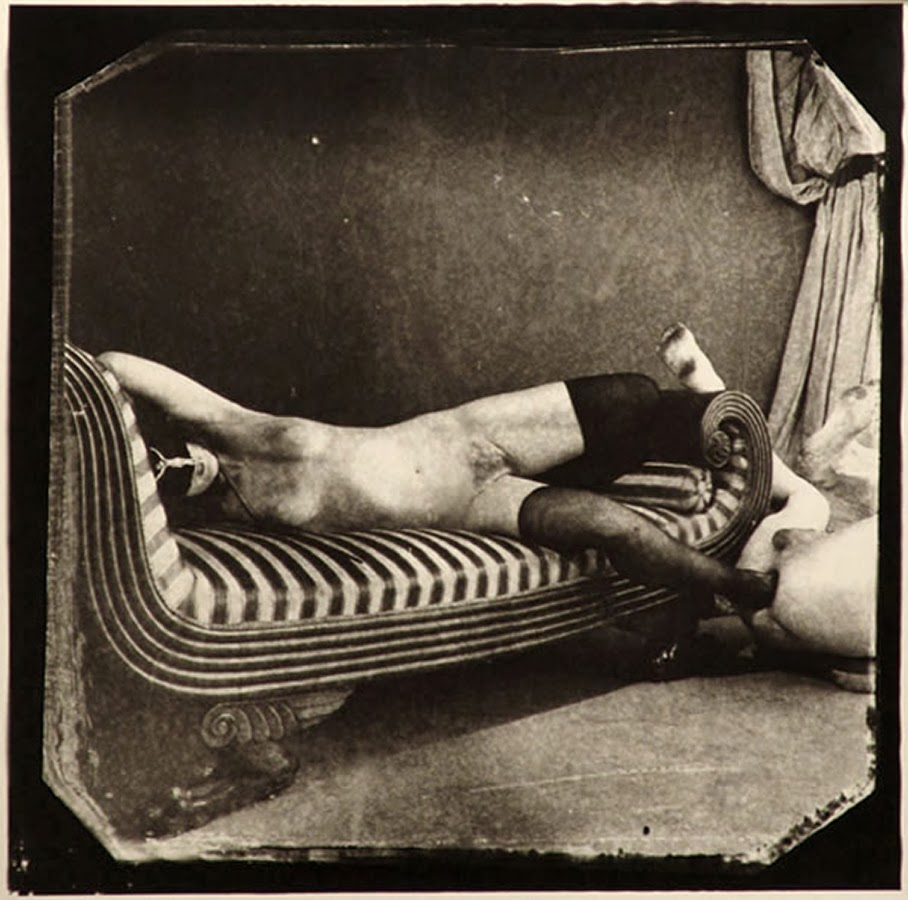

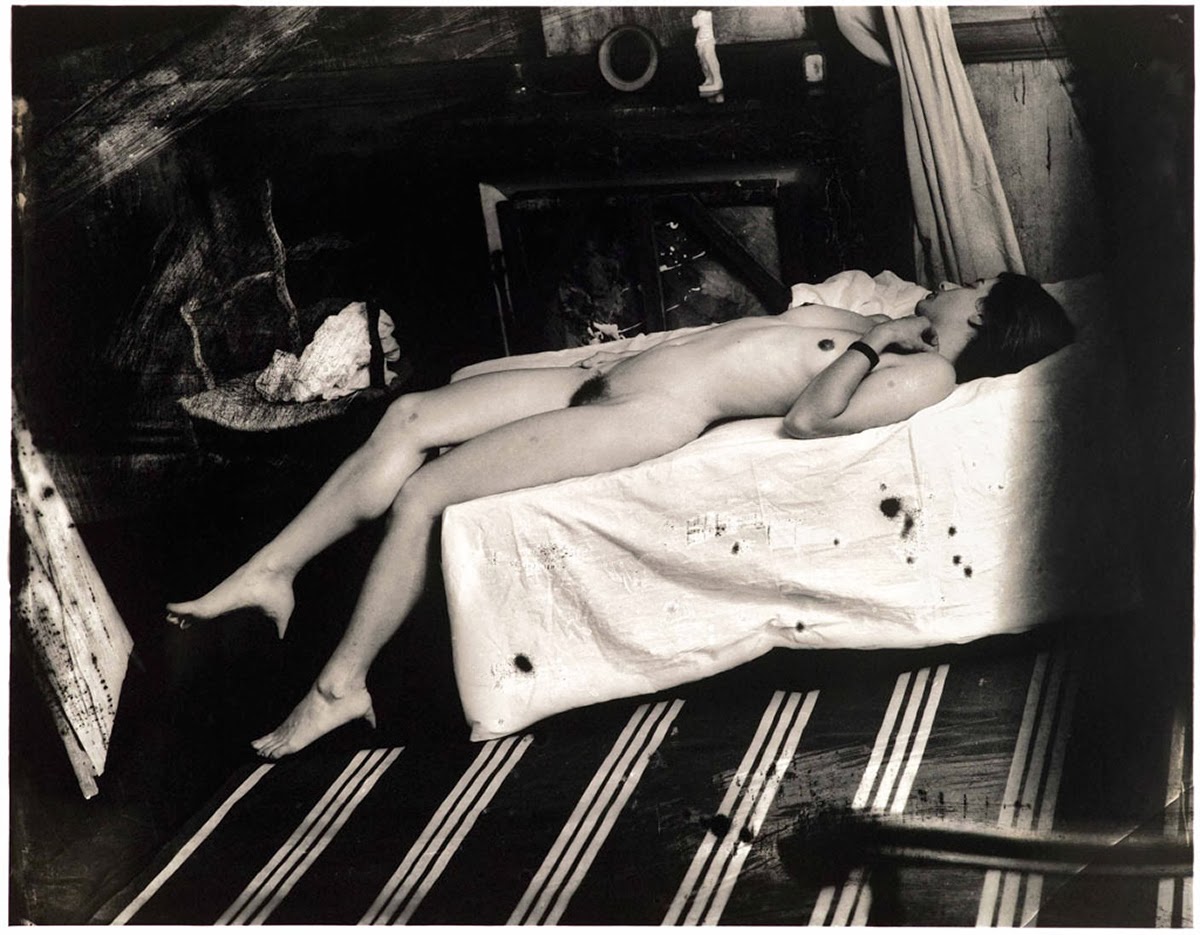

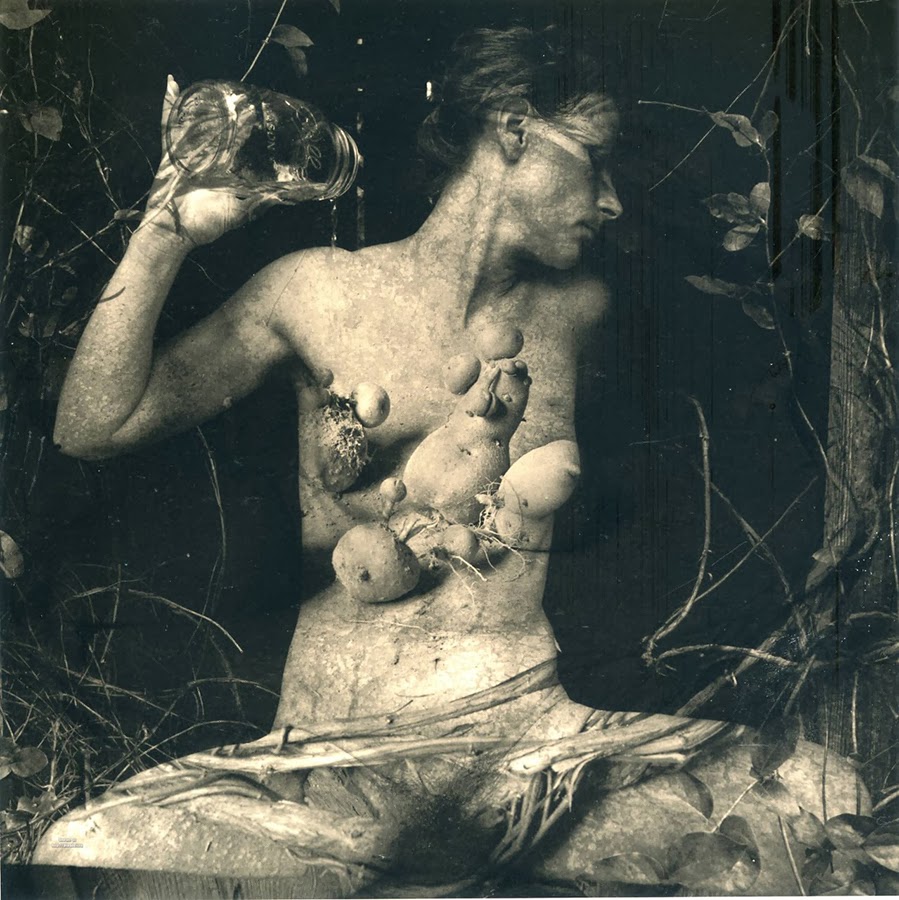

His photographic techniques draw on early Daguerreotypes and on the work of E. J. Bellocq; his techniques include scratching the negative, bleaching or toning the print, and using a hands-in-the-chemicals printing technique. This experimentation began after seeing a 19th-century ambrotype of a woman and her ex-lover who had been scratched from the frame. The resulting photographs are haunting and beautiful, grotesque yet bold in their defiance – a hideous beauty that is as compelling as it is taboo.

Witkin begins each image by sketching his ideas on paper, perfecting every detail by arranging the scene before he gets into the studio to stage his elaborate tableaus. Once photographed, Witkin spends hours in

the darkroom, scratching and piercing his negatives, transforming them into images that look made rather than taken. Through printing, Witkin reinterprets his original idea in a final act of adoration.

Some of Witkin’s works, namely those with corpses in them, have had to be created in Mexico in order to get around restrictive US laws. Because of the transgressive nature of the contents of his pictures, his works have been labeled exploitative and have sometimes shocked public opinion.

Visiting medical schools, morgues and insane asylums around the world, Witkin seeks out his collaborators, who, in the end, represent the numerous personas of the artist himself.

“I stayed in Mexico City for four extra days when I was making Glass Man, because I wasn’t getting the bodies I wanted. When bodies are brought in from the street, there’s sometimes a doubt as to how the

person died. Street people may be found days later, which makes it hard to determine the cause.

I’m in this room with a dead guy. I’m propping him up, and I put a fish in his hand as a kind of prop, and I’m checking the lighting. Then I get that straight, and I take a few photographs, just as a kind of a record. Then I make arrangements to have the guy autopsied. And as soon as he’s being autopsied, he starts changing! He’s on the table, and he’s changing. I turn to my Mexican translator, who is a very, very bright man, and we have seen the same thing. He says, “He’s being judged. This guy is being judged right now.”

Suddenly, he’s not a punk any more. He’s gone through this kind of transfiguration on the table, on the autopsy table.

When they were carrying the brain, I said, “Look at this brain–it may have contained thoughts of evil, but however he was judged, he is now a different presence!”

When I got him back, and I put him in this room, I got him on this chair, and I photographed him sitting down. Then I spent an hour and a half with him, and after that, he looked like a Saint Sebastian. He looked like a person who had grace. His fingers, I swear to God, had grown 50 percent. They were elegant. They were the longest fingers on a man I’ve ever seen. It was as if they were reaching for eternity.”

“I think most people aren’t aware that mortality has to do with life and death. Of course, not all of it is about mortal toil. But it’s about what happens in life. The mortuary, not coincidentally, is the place for the mortal remains.

Every moment is a moral decision. I believe there’s a moral codex in each of our hearts, and it’s a question of us finding our destinies and the purpose of that destiny. This life is a testing ground. It should be a sublime testing ground.”

“There’s this great story I know about a wanderer somewhere in a desert. He’s walking along, and he hears the smashing of steel and rocks in the distance. He goes out there to where the sound is, and two men are crushing stones in the heat. He approaches one, who seems very, very angry, and he’s cursing. The wanderer goes up to him and says, “What are you doing?” The man says, “I’m breaking the stones.” The wanderer approaches the other man. This one is also smashing rocks, but he’s not angry. The wanderer says, “What are you doing?” The man responds, “I’m building a cathedral.”

In July 2011, filming began on a feature length documentary titled “Joel-Peter Witkin: An Objective Eye”. The film, directed by Thomas Marino, takes a profound and introspective look into Witkin’s life and art. Along with all new in-depth interviews with Joel-Peter Witkin, the film features interviews from gallery owners, prominent artists, musicians, photographers, and scholars who share insight into the impact of Witkin’s work and influence on modern culture. Filming took place in Albuquerque, Los Angeles, New York, and Paris. The film will be released on July 1, 2013 and will be part of the permanent collection at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, France.

References:

Joel-Peter Witkin at the Catherine Edelman Gallery

Joel-Peter Witkin: An Objective Eye

Joel-Peter Witkin at zonezero.com

Comments

Joel-Peter Witkin — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>