Louise Brooks: Lulu the Lost

Born in Cherryvale, Kansas on November 14, 1906, Louise Brooks was the daughter of local attorney Leonard Porter Brooks, and Myra Rude, a talented pianist who played the latest Debussy and Ravel for her children and inspired them with a love of books and music.

When she was nine years old a neighborhood predator sexually abused Louise. This event had a major influence on Brooks’ life and career.

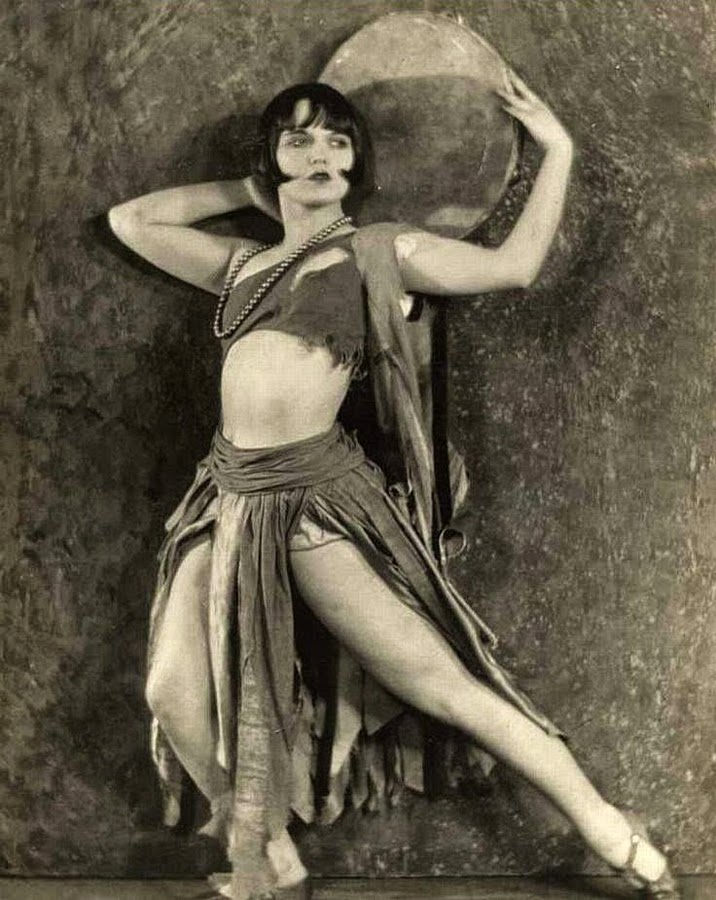

In 1922 the 16 year old Brooks joining the Denishawn modern dance company in Los Angeles, beginning her entertainment career as a dancer. By her second season with the company she had advanced to a starring role opposite Ted Shawn; but a long-simmering personal conflict between Brooks and Shawn’s wife and co-founder of the company, Ruth St. Denis, boiled over and St. Denis abruptly fired Brooks from the troupe in 1924, telling her in front of the other members that “I am dismissing you from the company because you want life handed to you on a silver salver”.

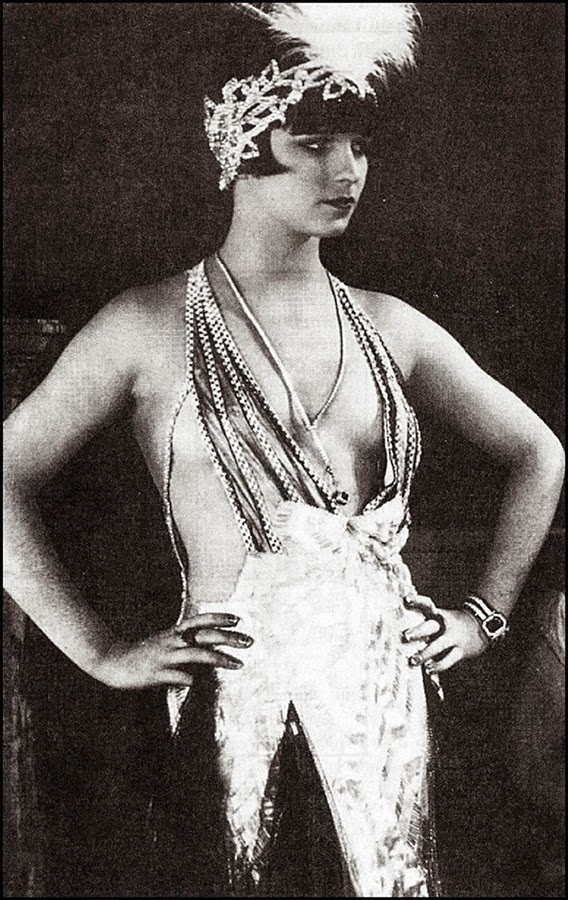

With help from friends Louise almost immediately landed a place as a chorus girl in George White’s Scandals, quickly followed by an appearance as a featured dancer in the 1925 Broadway edition of the Ziegfeld Follies.

It wasn’t long before she came to the attention of Paramount Pictures producer Walter Wanger, who signed her to a five-year contract with the studio that same year. Brooks immediately launched an affair with Charlie Chaplin, who was in town for the premiere of his film The Gold Rush.

Brooks made her screen debut in an uncredited role in the 1925 silent film The Street of Forgotten Men. She took the female lead in a number of silent light comedies and flapper films over the next few years, starring with Adolphe Menjou and W. C. Fields among others. In Howard Hawks’ acclaimed 1928 “buddy film”, A Girl in Every Port Brooks’ pivotal role as a sultry vamp brought her to the attention of the European film world.

In the summer of 1926, Brooks married film director Eddie Sutherland; but by 1927 she had fallen “terribly in love” with George Preston Marshall, owner of a chain of laundries and future owner of the Washington Redskins football team. She divorced Sutherland, mainly due to her budding relationship with Marshall, in June 1928. By now Brooks was mixing with the rich and famous, and she was a regular guest of William Randolph Hearst and his mistress, Marion Davies.

Louise was well known for her distinctive bobbed haircut, which she had originally worn in a wave but later smoothed out in European fashion. Although this wasn’t exactly unique (the style had been around since about 1915) women soon began copying her and fellow film star Colleen Moore. Within a few years it would become an icon of the “flapper”.

In 1928 Brooks played an abused country girl on the run with hobos Richard Arlen and Wallace Beery in the film Beggars Of Life. Soon after the film was made she left Paramount after being denied a promised raise. Brooks had come to despise the Hollywood “scene”, and left for Europe to work with prominent Austrian expressionist director G. W. Pabst. Paramount had tried to use the heralded coming of sound films to pressure Brooks to stay with them, but she called the studio’s bluff; 30 years later that rebellious move would come to be seen as arguably the smartest of her career, securing her immortality as a silent film legend

and independent spirit.

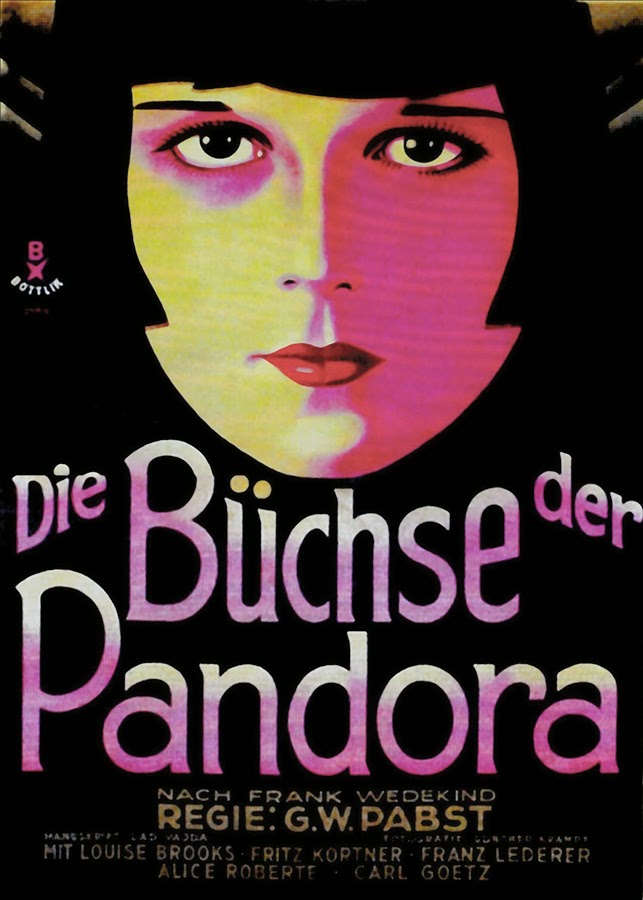

Pabst tagged Brooks to star in his 1929 film Pandora’s Box, a masterpiece of his New Objectivity period. The film is based on two plays by Frank Wedekind (Erdgeist and Die Büchse der Pandora) and Brooks plays the central figure, Lulu. The film was notable for its frank treatment of modern sexual mores, including one of the first screen portrayals of a lesbian. That same year she also starred in Pabst’s controversial social drama Diary of a Lost Girl based on the book by Margarete Böhme, and in 1930 Louise headed to France to star in Prix de Beauté by Italian director Augusto Genina, her first sound film.

At the time of their release these films were considered shocking for

their portrayals of sexuality, and they were all heavily censored. In

France Pandora’s Box was re-edited to the point that audiences had difficulty following the plot line. On December 2, 1929, The New York Times called Pandora’s Box “…a disconnected melodrama …[with] a seldom interesting narrative.” But the film was re-discovered by critics in the 1950s to great acclaim, and today it is considered one of the classics of Weimar Germany’s cinema.

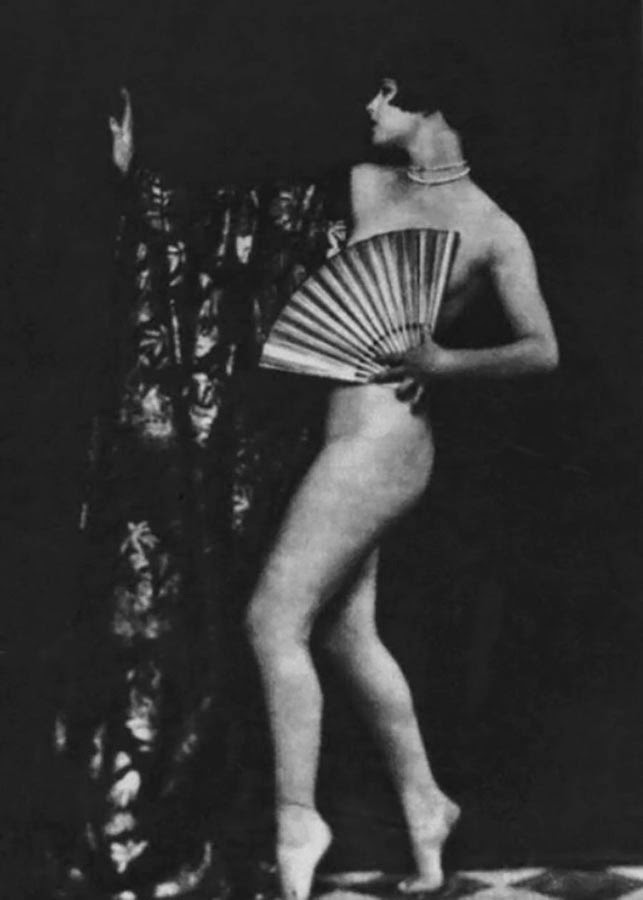

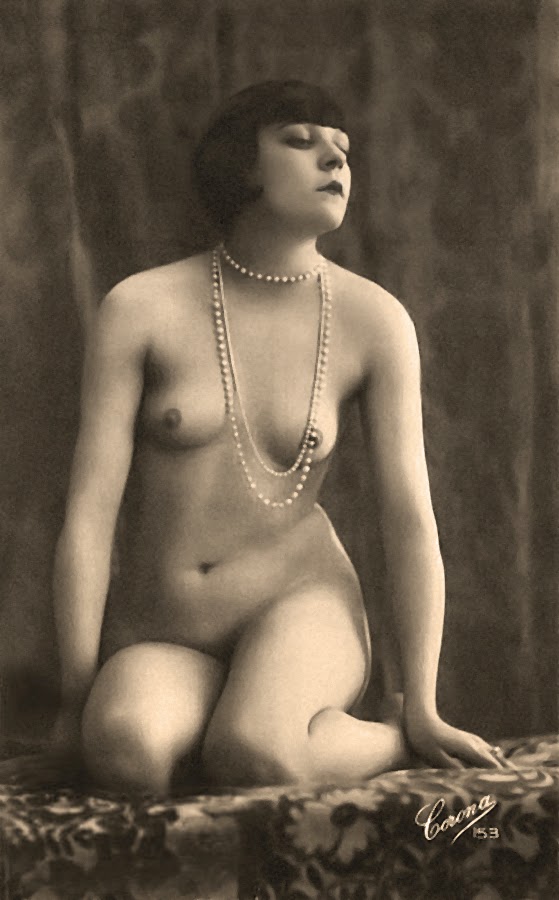

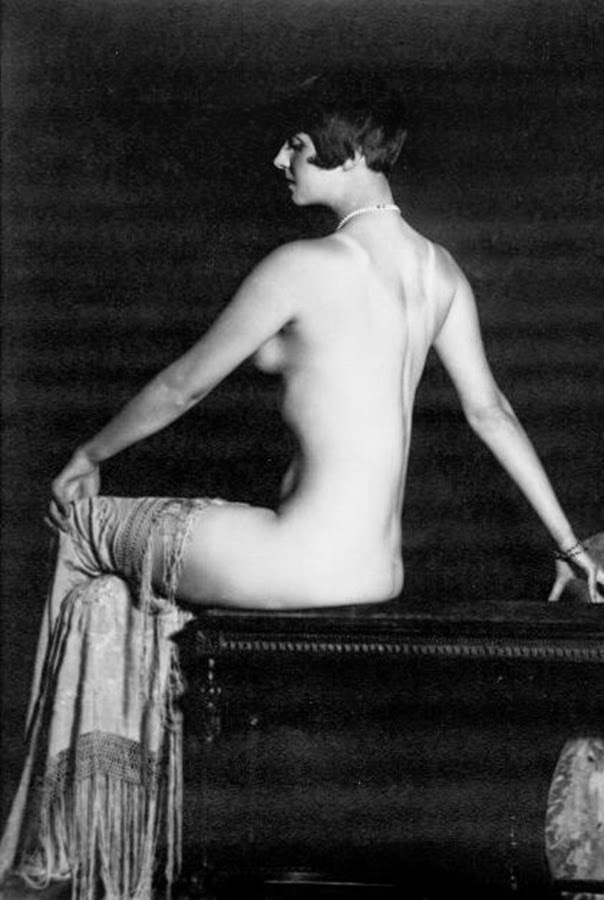

Brooks posed for many of the leading photographers of her time, including Edward Steichen, James Abbe and Alfred Cheney Johnston. She had no qualms in posing nude; in the USA a number of these images were published in the “pin-up” magazines of the mid-1920’s such as Artist & Models. These publications mixed high art with scantily clad women and often featured film and stage starlets, particularly the

actresses and dancers who appeared in George White Scandals, Ziegfeld Follies and other Broadway shows. During her time in Europe several of the “French Postcard” publishers also released images of her, both original and copied from US photographers.

When Louise returned to the US in 1931 she was cast in two mainstream films: Warner Brothers’ God’s Gift to Women and Paramount’s It Pays to Advertise. While her initial snubbing of Paramount hadn’t really hurt her in Hollywood, when she refused the studio’s offer to do the sound retakes of the 1929 film The Canary Murder Case the outraged directors effectively blacklisted her, claiming that her voice was “unsuitable for sound pictures”. Actress Margaret Livingston was hired to dub Brooks’s voice for the film, and Brooks’ performances in the new films were largely ignored.

William Wellman, her director on Beggars of Life, offered her the female lead in The Public Enemy alongside rising star James Cagney. Brooks turned down the role to visit a lover in New York City; the part went to Jean Harlow, resulting in her own rise to stardom. Brooks later claimed that she simply “hated Hollywood”. Turning down Public Enemy marked the real end of Louise Brooks’s film career.

Louise Brooks declared bankruptcy in 1932 and began dancing in nightclubs to earn a living. In 1933 she married again, this time to Chicago millionaire Deering Davis, but she abruptly left him in March 1934 after only five months of marriage “without a good-bye… and leaving only a note of her intentions” behind. The couple officially divorced in 1938.

She attempted a comeback in 1936 and did a bit part in the Western Empty Saddles which led Columbia to offer her a screen test contingent on appearing uncredited in their 1937 musical When You’re in Love. She made two more films after that, including the lead opposite John Wayne in Overland Stage Raiders (1938), a “B” Western in which she played the romantic lead with a long hairstyle which made her virtually unrecognizable. Louise briefly returned to Wichita, but met with a cool reception. After an unsuccessful attempt at operating a dance studio she returned to the East Coast and, after some brief jobs as a radio actor and a gossip columnist, she took a job as a salesgirl for a few years at Saks Fifth Avenue in New York City.

By 1942 Louise had turned to prostitution; eking out a living as a courtesan with a few select wealthy men as clients.

“I found that the only well-paying career open to me, as an unsuccessful actress of thirty-six, was that of a call girl … and (I) began to flirt with the fancies related to little bottles filled with yellow sleeping pills.” During this period she began her first major writing project, an autobiographical novel called Naked on My Goat, a title taken from Goethe’s Faust. Unfortunately she destroyed the manuscript before it was finished.

By her own admission, Brooks was a sexually liberated woman, and her liaisons with many people in and around the film industry were legendary. She enjoyed fostering speculation about her sexuality, cultivating friendships with lesbian and bisexual women including Pepi Lederer and Peggy Fears, but eschewing relationships. She admitted to some lesbian dalliances, including a one-night stand with Greta Garbo; later describing Garbo as masculine but a “charming and tender lover”.

Despite all this, she considered herself neither lesbian nor bisexual:

“… when I am dead, I believe that film writers will fasten on the story that I am a lesbian. I have done lots to make it believable… all my women friends have been lesbians. But …there is no such thing as bisexuality. Ordinary people, although they may accommodate themselves, for reasons of whoring or marriage, are one-sexed. Out of curiosity, I had two affairs with girls – they did nothing for me“.

Sadly, many of Louise Brooks’ American silent films are lost. But French film historians rediscovered her films in the early 1950s, and much to her amusement began proclaiming her as an actress surpassing even Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo as a film icon. This led to the introduction of still ongoing Louise Brooks film revivals, and rehabilitated her reputation in America.

James Card, film curator for the George Eastman House, discovered Brooks living as a recluse in New York City and persuaded her to move to Rochester, New York to be near the George Eastman House film collection. With Card’s help Brooks’ second career as an insightful writer took shape. Throughout the 50’s, 60’s and ’70’s her essays regularly appeared in magazines like Sight and Sound, Film Culture, and Focus on Film. In the 1970s she was interviewed extensively on film for the documentaries Memories of Berlin: The Twilight of Weimar Culture (1976), produced and directed by Gary Conklin, and for the documentary series Hollywood (1980) by Brownlow and David Gill. Lulu in Berlin (1984) is another rare filmed interview, produced by Richard Leacock and Susan Woll. In 1982, a bestselling and widely reviewed collection of her work appeared under the title Lulu in Hollywood.

On August 8, 1985, Louise Brooks was found dead of a heart attack after suffering from arthritis and emphysema for many years. She was buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

She had no known survivors.

References:

The Louise Brooks Society

Classic Hollywood: Louise Brooks’ rise and fall; Susan King, Los Angeles Times, July 16 2012

Louise Brooks: Style Evolution; Jada Wong, Huffington Post