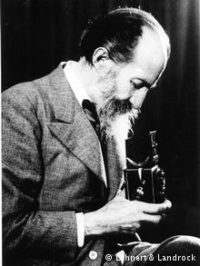

Rudolf Franz Lehnert was born in 1878 in Gross Aupa, Bohemia (now Velká Úpa, Czech Republic). Raised by his uncle in Vienna, he studied photography at the Vienna Institute of Graphic Arts and at the age of 21 he used the money he had inherited from his parents to begin traveling. He roamed Europe on foot, and was especially interested in Palermo, the hub of artists in Italy.

Rudolf Franz Lehnert was born in 1878 in Gross Aupa, Bohemia (now Velká Úpa, Czech Republic). Raised by his uncle in Vienna, he studied photography at the Vienna Institute of Graphic Arts and at the age of 21 he used the money he had inherited from his parents to begin traveling. He roamed Europe on foot, and was especially interested in Palermo, the hub of artists in Italy.

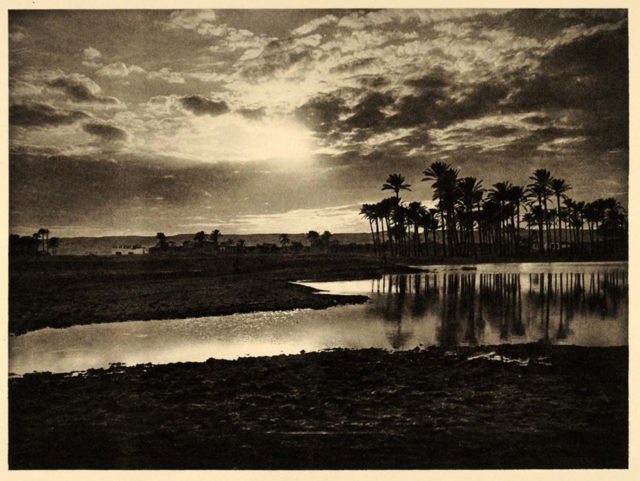

In 1903 Lehnert sailed to Tunisia with the intention of hiking through the country; he fell in love with the southern oases, and took numerous photos of the people and the desert. On his return to Europe a year later, he traveled to Switzerland by coincidence met a young German student, Ernst Heinrich Landrock.

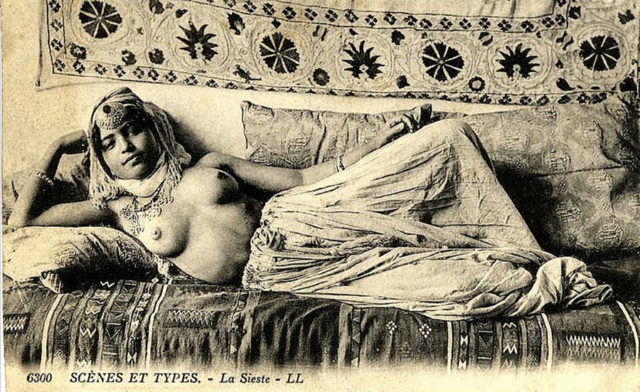

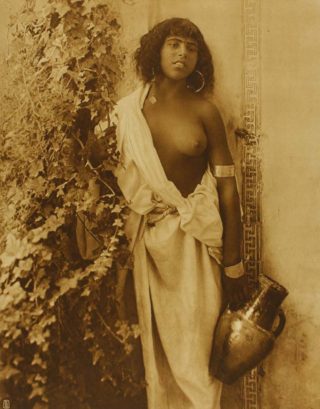

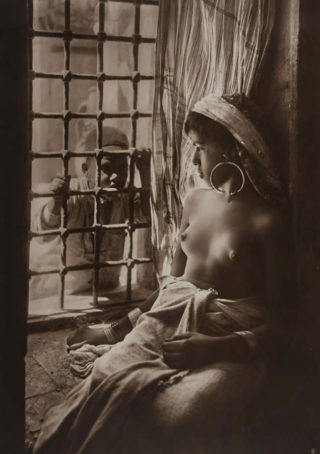

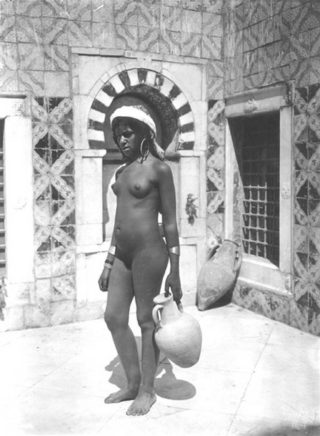

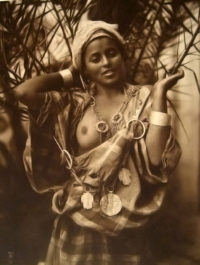

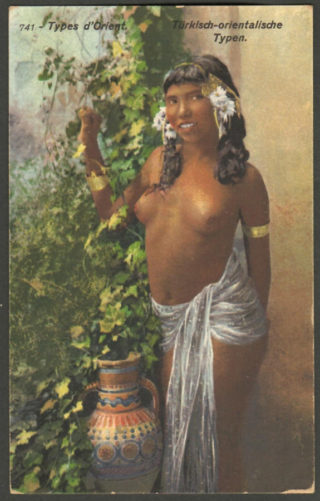

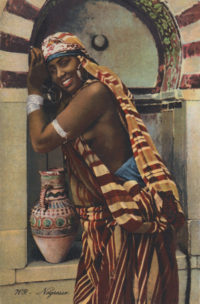

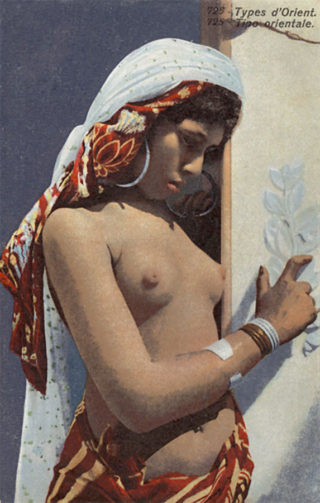

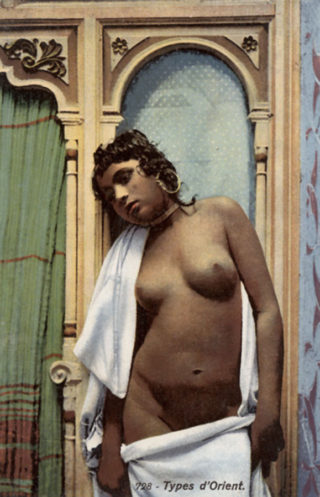

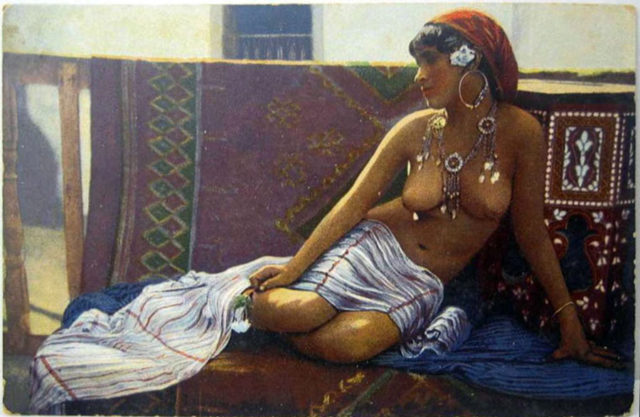

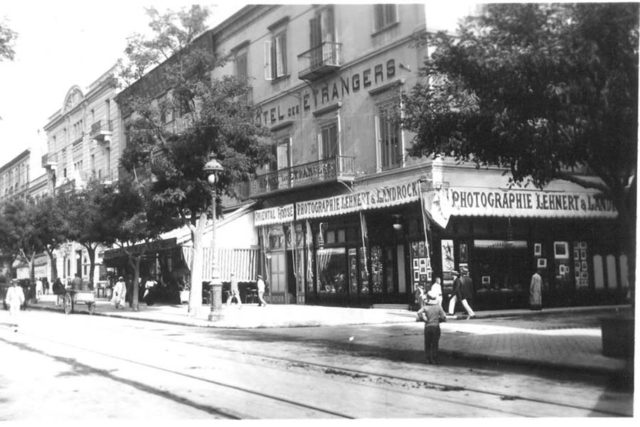

Landrock was impressed by Lehnert’s photography skills, and by his knowledge of the country. “Orientalism” had become a popular theme in art and literature at the turn of the 18th century, and Landrock believed that they could turn Lehnert’s photos into a profitable business. They began publishing the photos in Munich and Leipzig, and the same year (1904) the two partners took passage to Tunis and opened a photo studio in the capital, “Lehnert and Landrock” on Avenue de France, with Lehnert as the photographer and Landrock the administrative director. Under recent French colonization, European settlements in Tunisia were actively encouraged and several books document their successful work in the following years. By 1908 they had become well known, and had already won awards for “best photos” in Paris.

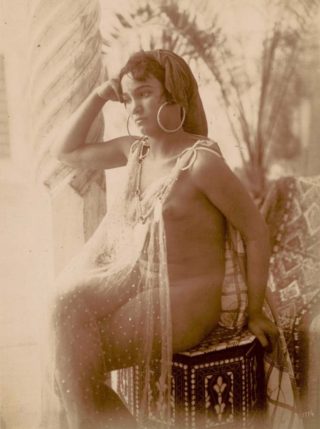

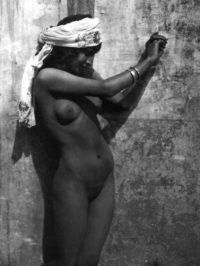

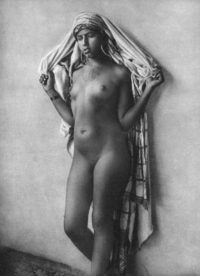

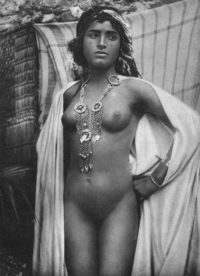

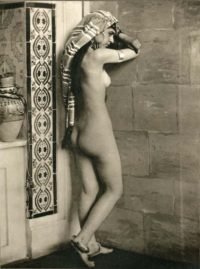

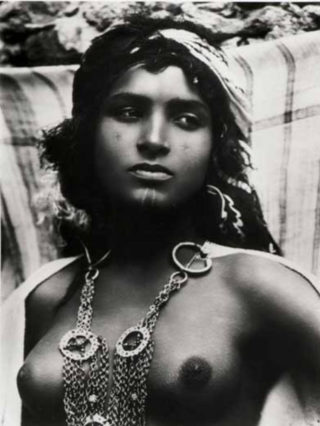

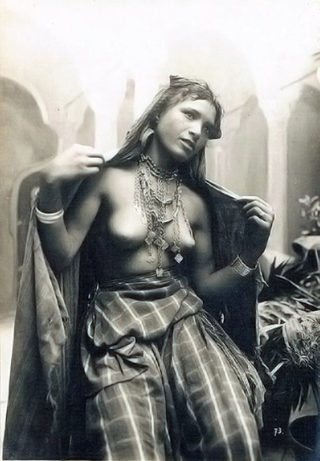

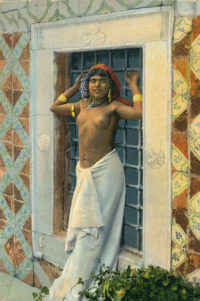

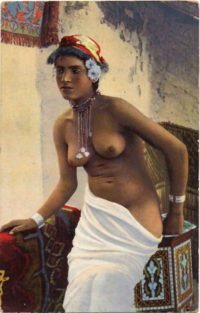

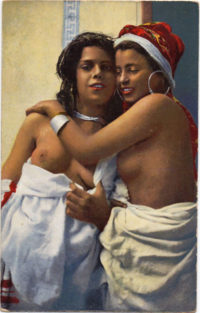

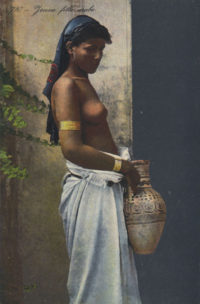

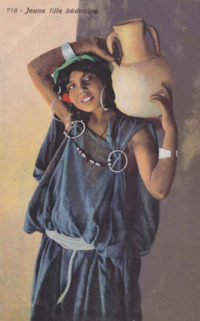

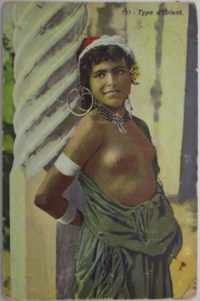

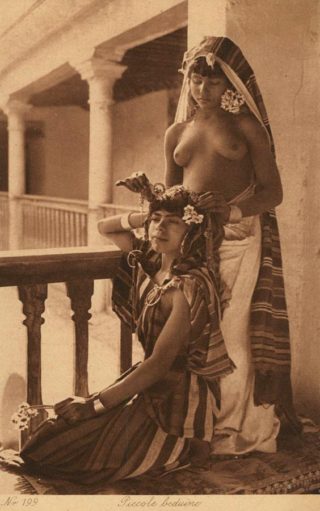

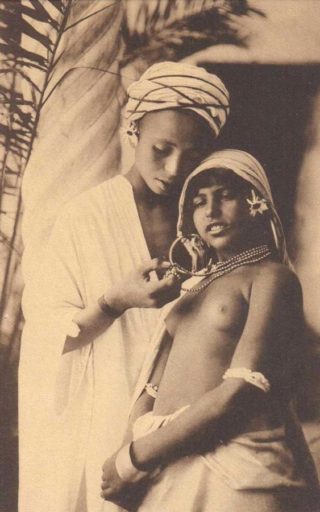

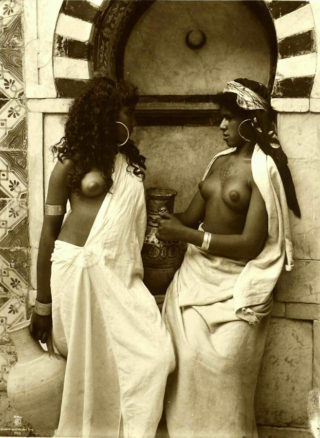

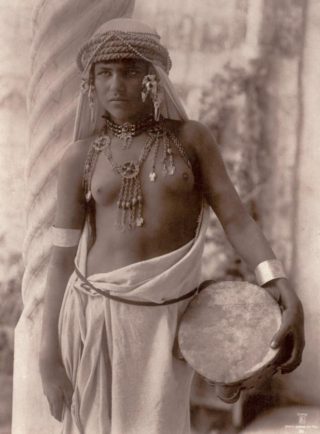

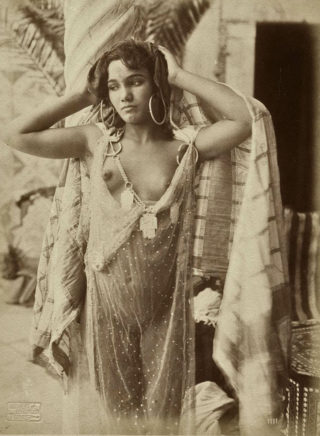

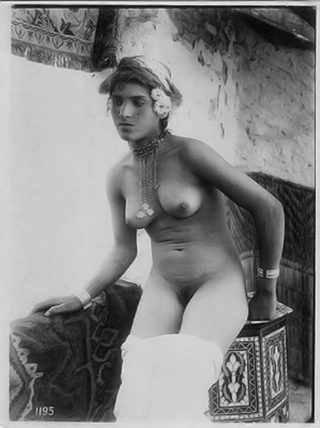

Portraits were Lehnert’s specialty; the pictures highlighted the rare beauty of desert people who seldom wanted to be photographed, with the exception of the Awlad Nael tribe in Algeria, which was, according to Lambelet, “where people loved music and dance and women got to choose their husbands.” For the next several years they toured the Mediterranean and made numerous photo collections, and many of the Orientalist painters who never set foot in the region used their photos for inspiration.

But in 1914 the shadow of World War I fell across Northern Africa, and Landrock, being a German, was arrested by the French colonial police.The studio was closed and all contents were confiscated by the government. Landrock was first destined for a concentration camp, but an agreement between France and Germany allowed prisoners with no military service history or with health problems to be imprisoned in Switzerland.

Lehnert, meanwhile, had been on a caravan in the middle of the Maghreb desert between Algeria and Tunisia and was not even aware that war had broken out. Upon his return to Tunis he was surprised to see the shop closed and his entire library of glass plates seized. Shortly after, on 4 August 1914, he was also arrested and sent to an internment camp in Corsica.

Landrock, stranded in Switzerland, was trying desperately to find a way to rescue his friend and “by detours” he finally managed to get Lehnert to Davos. At this point, both men were apparently married: Lehnert to Ms. Eugenie Schmitt and Landrock to Ms. Emilie Singer-Lambelet.

As the war came to a close and European borders shifted once more, Bohemia became the core of the newly formed country of Czechoslovakia. Fortunately for Lehnert & Landrock, the Lehnerts’ new homeland was an ally of France and complex bureaucratic proceedings with the French authorities eventually led to the return of the confiscated glass plates. The recovered plates were quickly re-engraved in Leipzig; having lost them once, they were not about to risk losing them again.

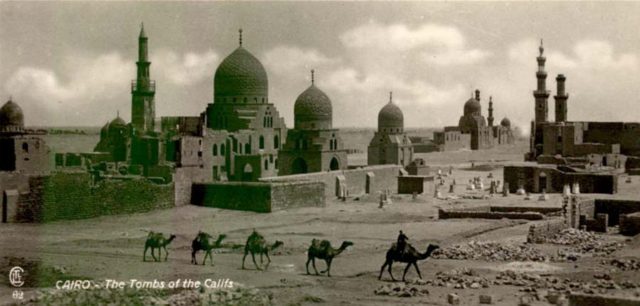

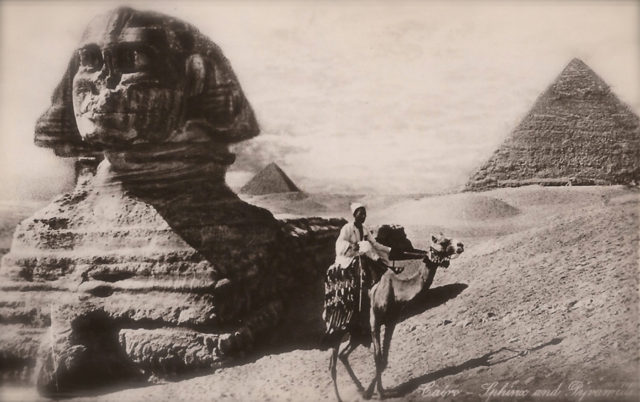

The partners wanted to start again somewhere on the Mediterranean. Lehnert wanted to go to Tunisia, but Landrock preferred Cairo, especially with the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen which he felt would work to their marketing advantage.

In 1923 Lehnert left Europe accompanied by an assistant on a trip through Egypt, Palestine and Lebanon. As previously agreed the Landrocks, including Landrock’s step-son Kurt Lambelet, reached Alexandria on the boat Tereve and launched their new incarnation of the Lehnert and Landrock atelier in the Benanni Building at No.21 Maghrebi Street, downtown Cairo.

In Cairo the partners’ working arrangement was déja vu: Lehnert traveled around the country photographing faces and crowded urban landscapes; for several years focusing on Egypt’s historical heritage, monuments and landscapes, which were in high demand. But as a portrait artist he missed the openness of the Tunisians and felt that the Egyptians were too camera-shy. Nonetheless, his photography collection From Alexandria to Abu Simbel and his 400 photos of the Egyptian museum were artistic gems that were well received.

Landrock had 200 boxes of hand colored engravings and photographs shipped to markets in Dresden, Berlin and Leipzig, but the business was slower than expected and they had to take out a sizeable loan. The marketing problems called for a shift in thinking: Lehnert & Landrock began to sell their products directly in their Cairo studios. Postcard fever had swept across Europe and America during the first decade of the century, and Lehnert & Landrock were by no means the first to sell photos of the world’s foremost tourist-Mecca.

By 1930, Lehnert sold his share to Landrock and traveled with his wife and daughter back to Tunisia, where he opened his own studio on Avenue Jules Ferry in Tunis. He left the rights to his pictures to Landrock, who continued to run the company in Cairo together with his step-son Kurt Lambelet. However, with the approach of a second World War in 1938, Landrock feared a repeat scenario of their first disastrous brush with the authorities. He sold 80 percent of his shares to his stepson Kurt, who was a Swiss citizen and therefore from a neutral country. Landrock retired with his wife to southern Germany, as Kurt Lambelet desperately tried to adapt to the war-induced changes in Cairo.

By 1939 the Landrocks were stuck in Germany due to the war, and they retired there until Ernst Heinrich Landrock died in 1966. Lehnert meanwhile had stopped his own professional activities, and withdrew with his family to their house in Carthage.

In Cairo the British closed the supposed German shop and, as Landrock had feared, seized the entire contents. Fortunately Kurt Lambelet ‘s protests of his Swiss citizenship enabled him to get his 80 per cent share back, but he had to quickly adjust to a wartime situation. He began to stock local products like leather and silver jewellery which he sold as souvenirs to the allied soldiers. Because imported items from Germany are forbidden and everything from England was rationed, printing of Lehnert’s now famous images was limited to the then very poor local printing houses. Instead they switched to the trade they are still known for, and eventually became one of the two biggest English bookshops in Cairo.

After the death of his wife In 1944, Lehnert moved into the house of his daughter and son-in-law in Redeyef, Gafas, Tunisia. On 16th of January 1948, Rudolf Franz Lehnert died in Redeyef and was layed to rest beside his wife in Carthage.The following year the British turned over the remaining 20 per cent share of Landrock to Egypt, and on 19th of November Lambelet was finally able to purchase it and resume full ownership. He soon set about re-establishing the bookshop, expanding it with technical literature in English and re-opening a German language section.

Lehnert & Landrock was listed as a “postcard” retail store in all pre-World War II commercial directories, but by 1949 the company appeared in the Egyptian Directory as a “library” offering “technical & scientific books, maps, subscriptions to periodicals from all countries, and Photostat copies in 1 minute.”

The 1952 revolution in Egypt turned a new page and a national uprising literally set Cairo on fire, destroying shops owned by foreigners. Kurt Lambelet’s son, Dr. Edouard Lambelet, remembers: “Our Nubian employees rescued our bookshop from destruction. They protected it, as if it was their own property. Without our loyal Nubians we would have lost our shop. It was the most difficult time for us.”

In 1956 all major companies in Egypt were nationalized, but fortunately Lehnert & Landrock was too small. In January, 1965, Kurt Lambelet founded the “L & L. K. Lambelet & Co.” with Edouard and Georges Angelidis.

Edouard Lambelet left Egypt, returning to Switzerland to complete his schooling and military service. He went on to university studies in geology in Germany.

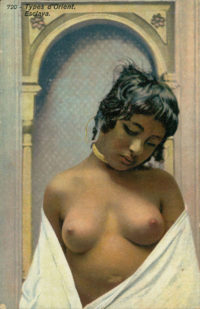

Edouard Lambelet rejoined his father’s Cairo business in 1979. In 1982, he discovered a box in the attic with 6,000 of Lehnert’s original glass plates. The fragile negatives were removed from the store, identified and catalogued. Attempts at reproducing the firm’s old prints from the newly rediscovered plates were an immediate success; demand snowballed when a story on the Lehnert & Landrock treasure trove appeared in the French periodical Liberation, prompting a renewed interest in old printing techniques. Exhibitions were organized in Switzerland and France, and the book Lehnert & Landrock, l’Orient d’un Photographe appeared in Lausanne in 1987. And as interest in the glass plate negatives continued to mount, it was decided to export the more risqué plates from “conventional” Cairo to the Elysée museum in Lausanne. In 1995 Concordia University began serious attempts at reproducing the glass plate negatives themselves.

Today Lehnert & Landrock remains as a famous landmark in downtown Cairo, still located at 44 Sherif St., close to Tahrir Square.

References:

Eastern races and beauty by Lehnert & Landrock

Lehnert & Landrock

The dangerous job of selling books in Cairo

The people behind the lens: Lehnert and Landrock