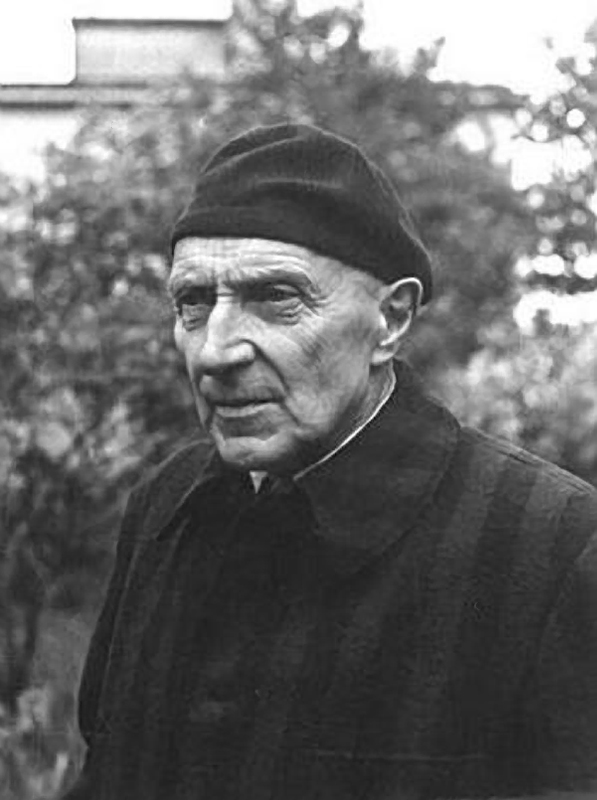

František Drtikol (March 1883, January 1961) was born and raised in the Central Bohemian city of Příbram, in what is now the Czech Republic. Příbram was primarily a mining town, but by the end of the 19th century it had developed a reputation for its artisans and craftsmen as the miners and their families augmented their income with traditional skills like woodcarving and metalwork.

František Drtikol (March 1883, January 1961) was born and raised in the Central Bohemian city of Příbram, in what is now the Czech Republic. Příbram was primarily a mining town, but by the end of the 19th century it had developed a reputation for its artisans and craftsmen as the miners and their families augmented their income with traditional skills like woodcarving and metalwork.

In 1901 Drtikol moved to Munich to study drawing and photography. The Art Nouveau movement was at its height: a movement defined by a desire to end all associations with classical themes and to combine both the fine and applied arts even to utilitarian objects, it also encompassed a philosophy that art itself should be a way of life. The great cities of Europe were being swept up in a wave of new design as everything from architecture to furniture adopted flowing curves and organic embellishments, and artists themselves were encouraged to adapt to multiple disciplines. Munich was a vibrant center of the movement, and by choosing to study photography -a relatively new medium combining science and art, technology and intuition- František Drtikol embraced it.

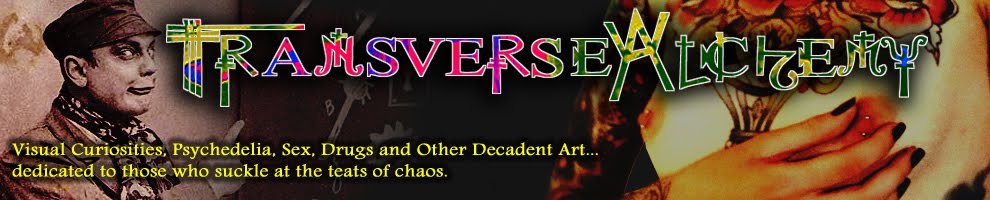

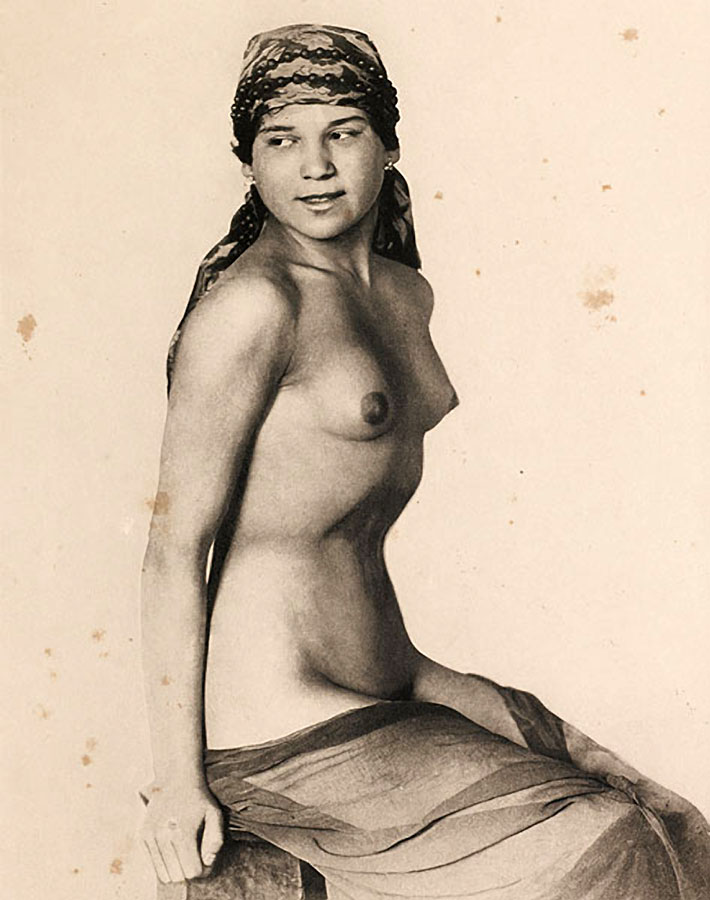

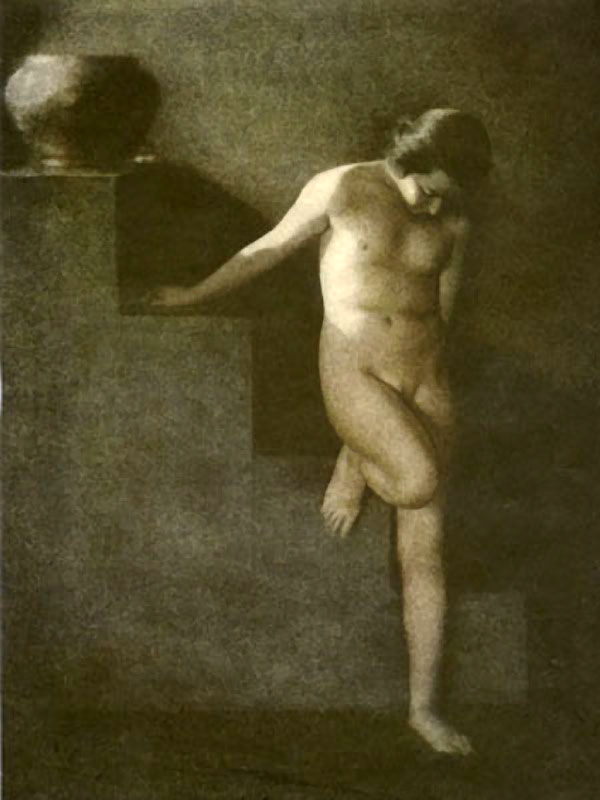

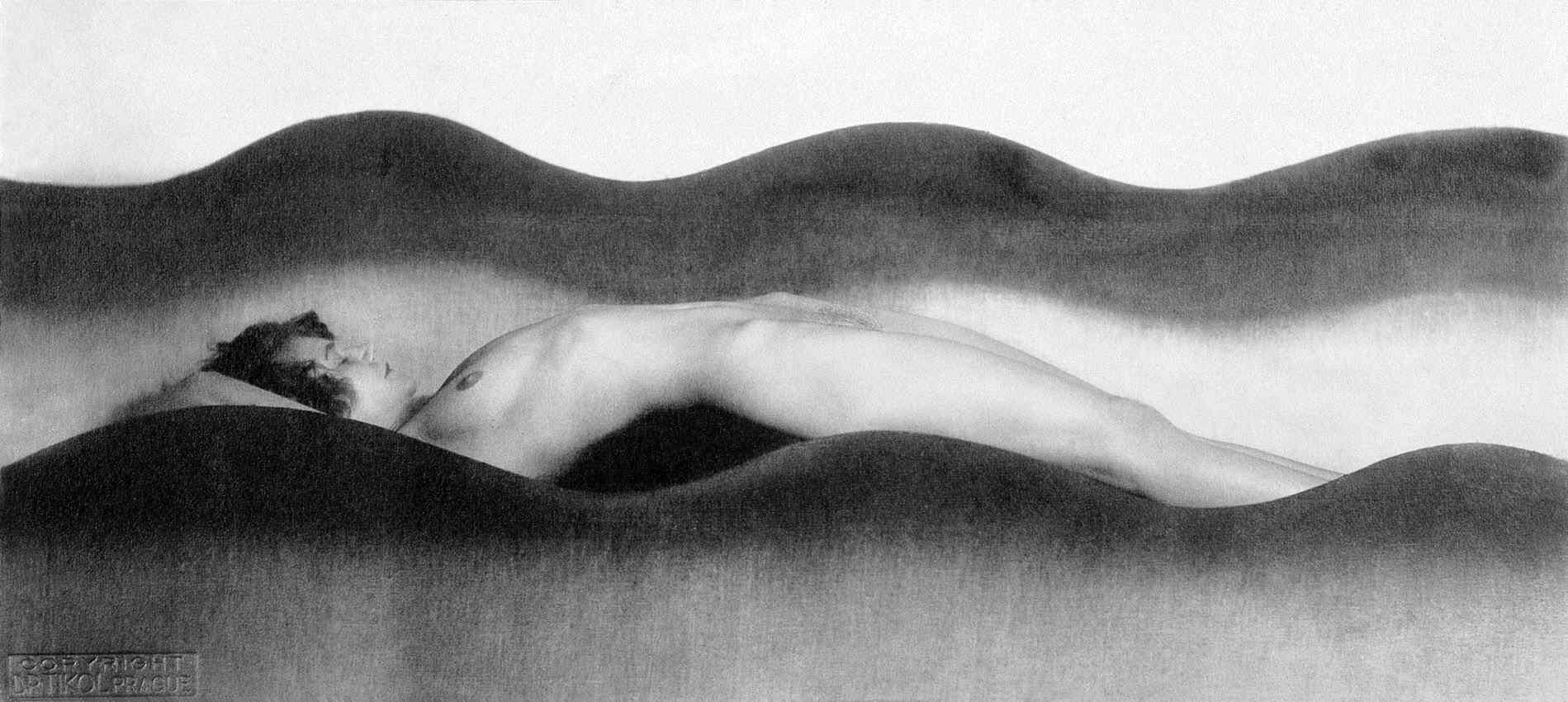

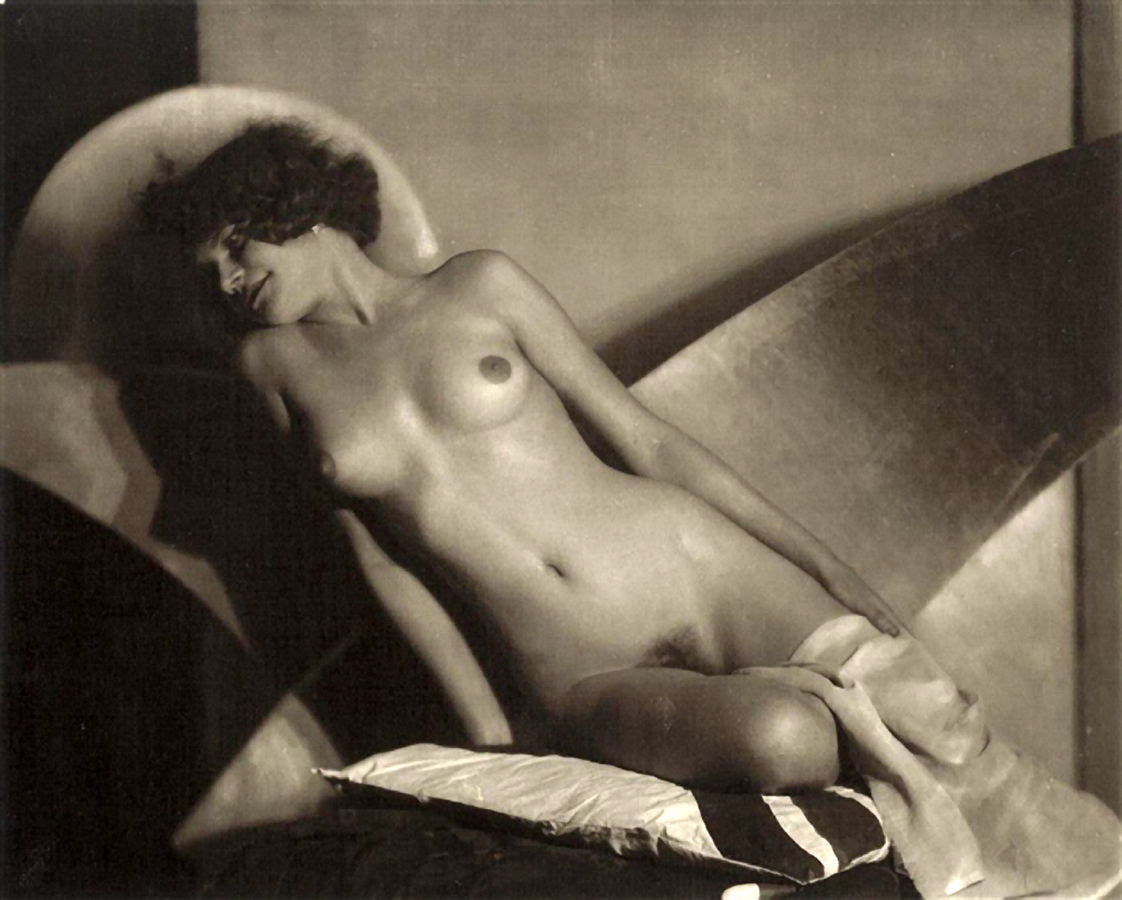

After four years of studies in Munich Drtikol returned to Prague for a brief period of apprenticeship with another photographer, then in 1910 he opened his own studio where he quickly developed a reputation as a portrait photographer. His clients included many of the most notable public figures of the day including then Czechoslovakian President Tomáš Masaryk, composer Leos Janacek and almost every artist living in or near Prague. Within a decade his studio was famous throughout Europe.But while portraiture was the means by which he supported his studio and made a comfortable living, Drtikol made his creative reputation through his nude studies. If his portraiture was elegant and refined, his nude studies were daring and inventive and the epitome of avant garde.

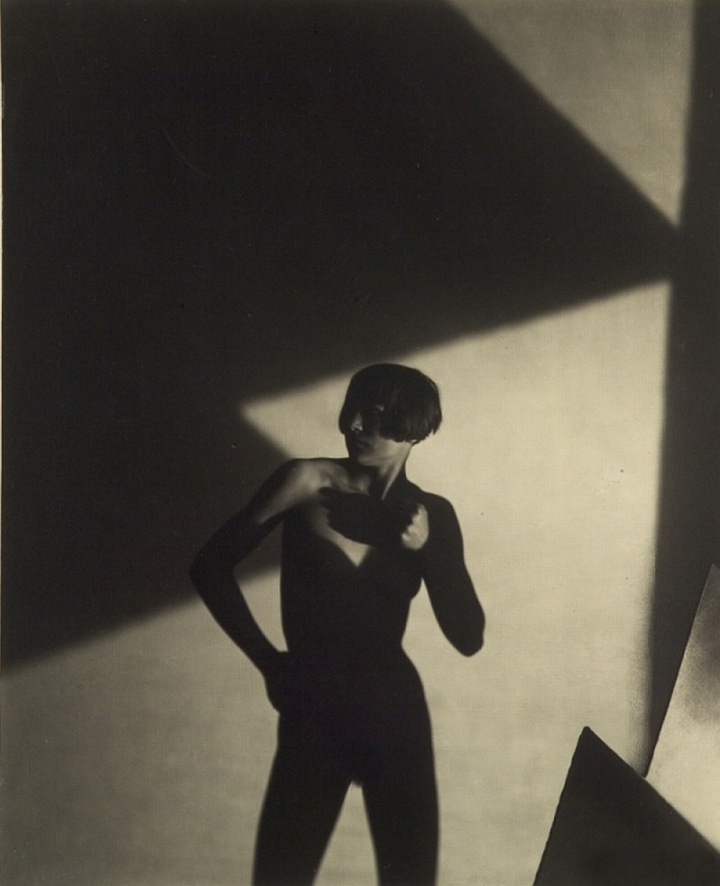

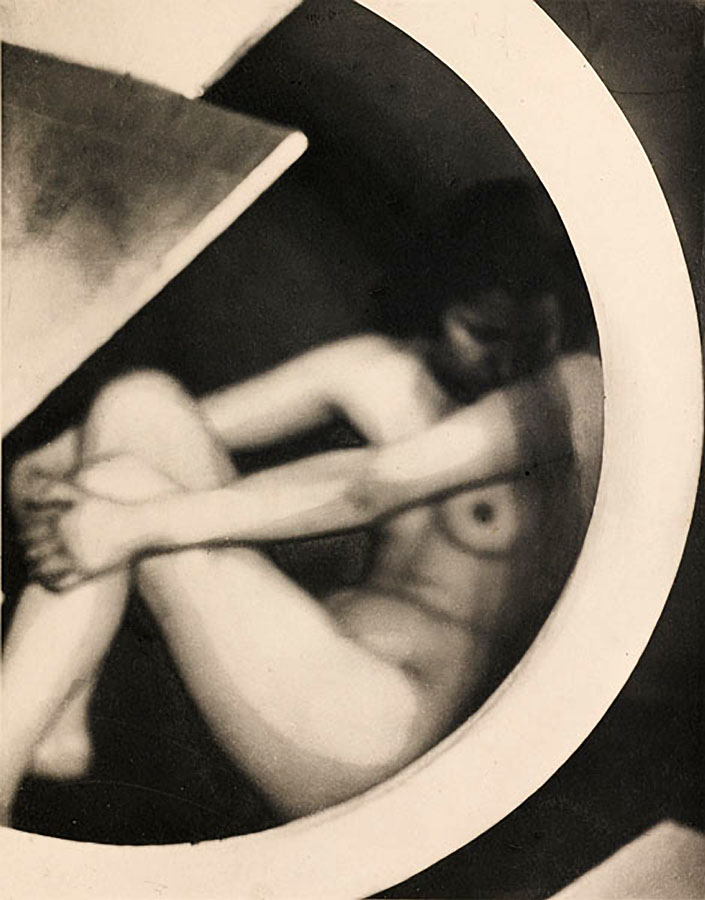

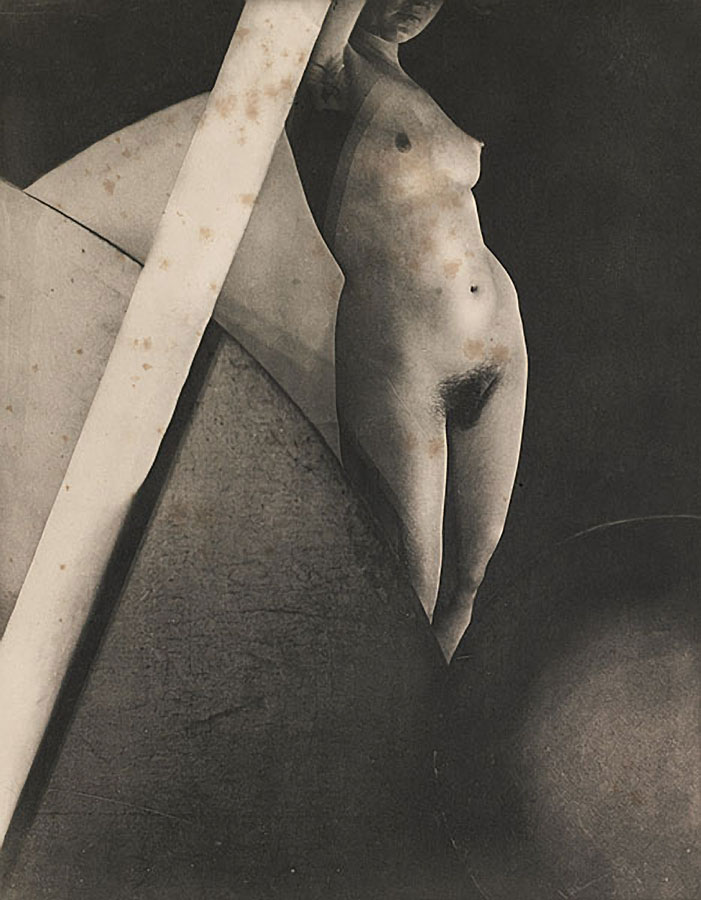

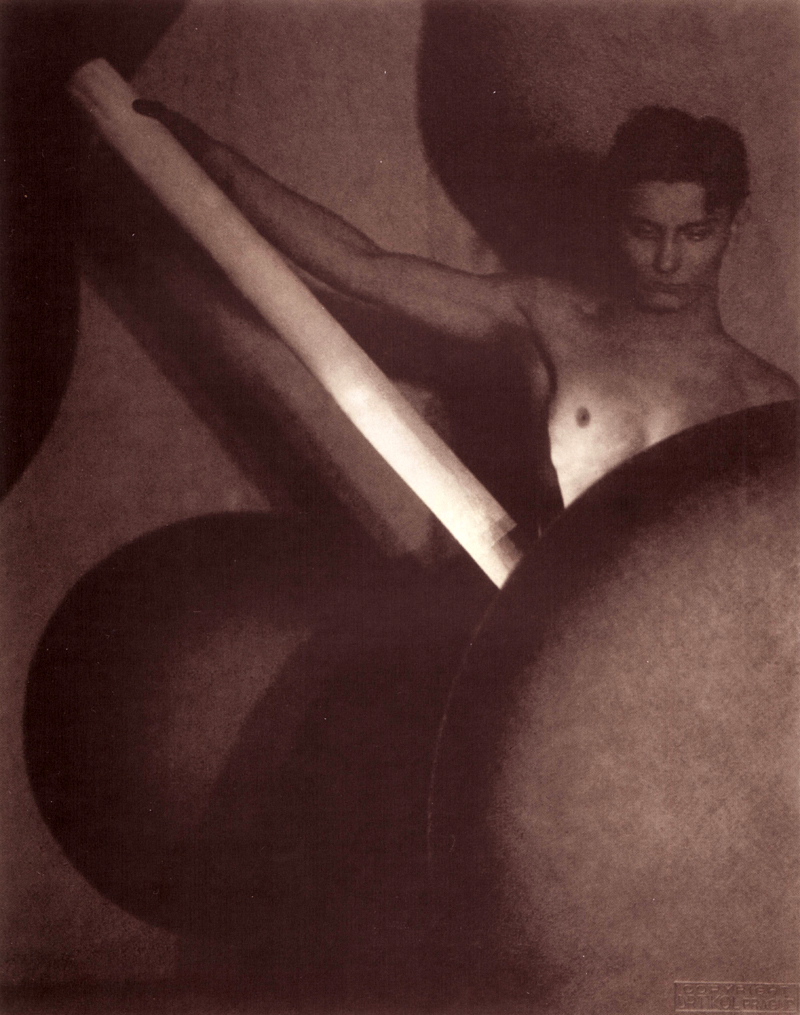

By the early 1920’s Art Nouveau had been upstaged by Art Deco. Deco’s linear symmetry was a distinct departure from the flowing asymmetry and organic curves of the Nouveau movement; it embraced influences from Cubism and Modernism, and drew its inspirations from ancient Egyptian and Aztec forms and introduced contemporaneous concepts of ‘streamlining,’emphasizing reiteration of shape and form.

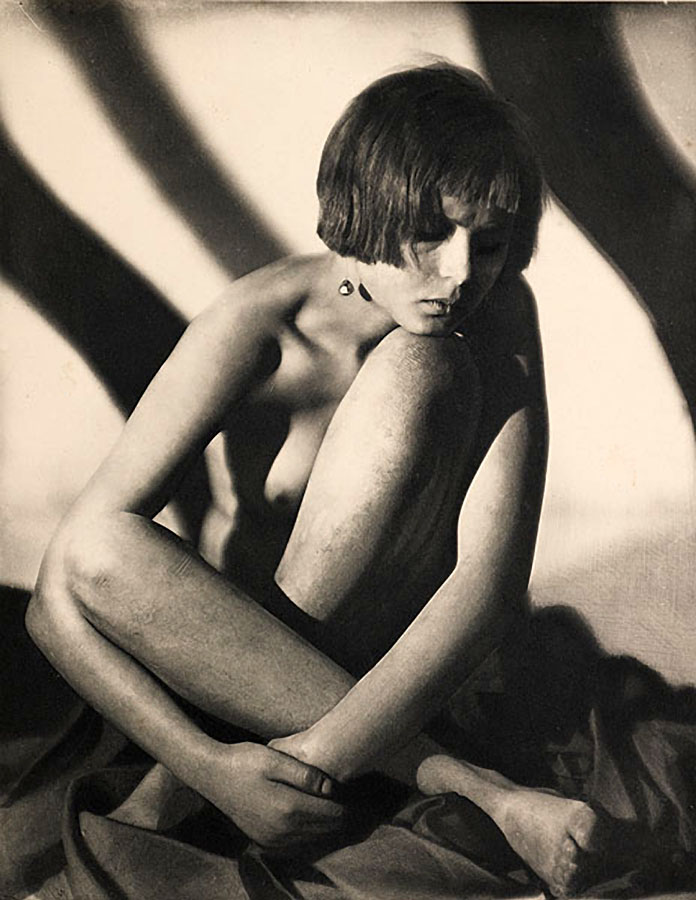

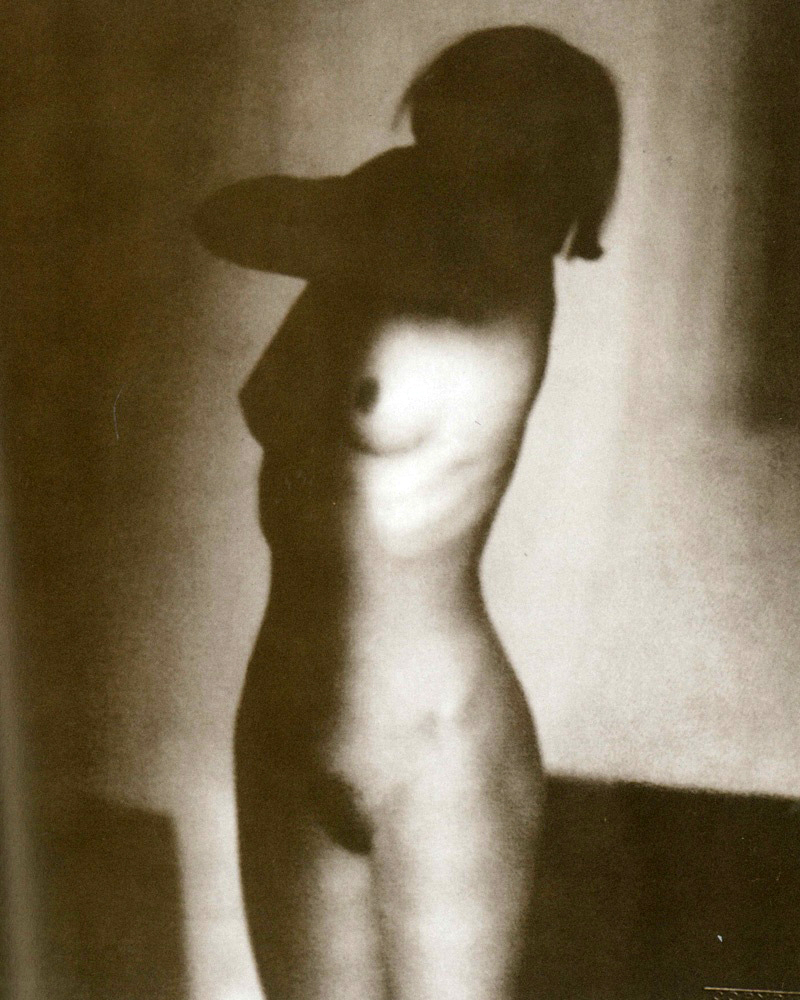

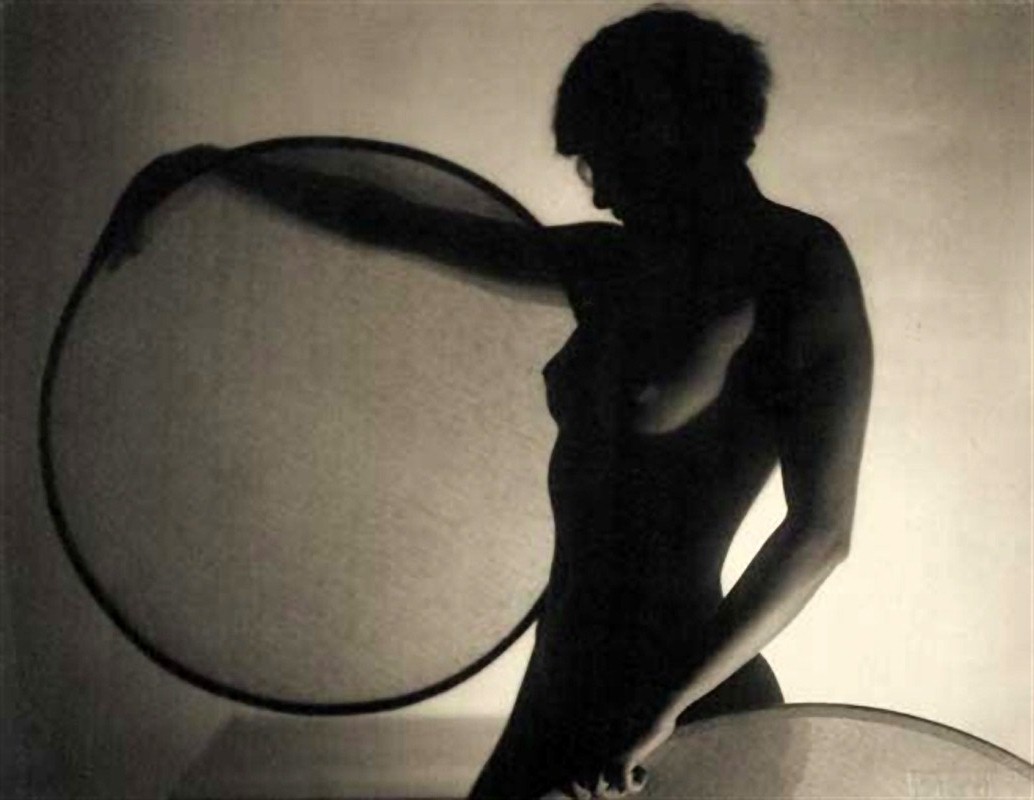

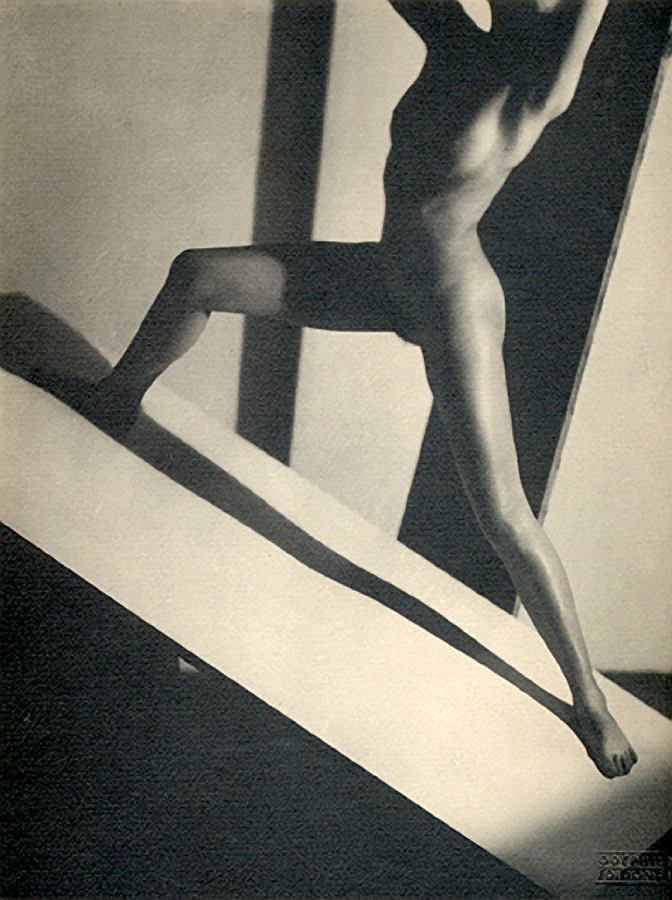

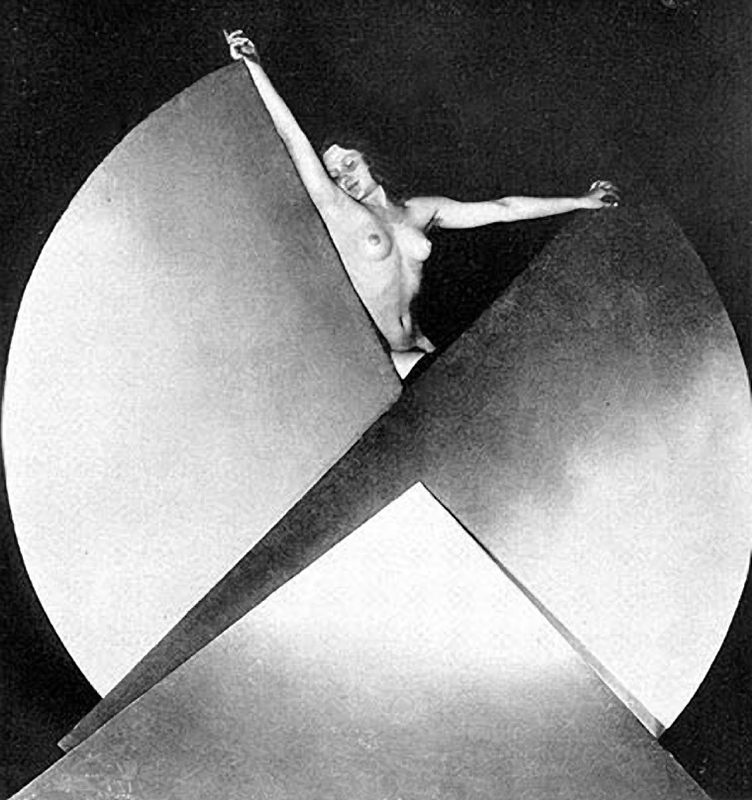

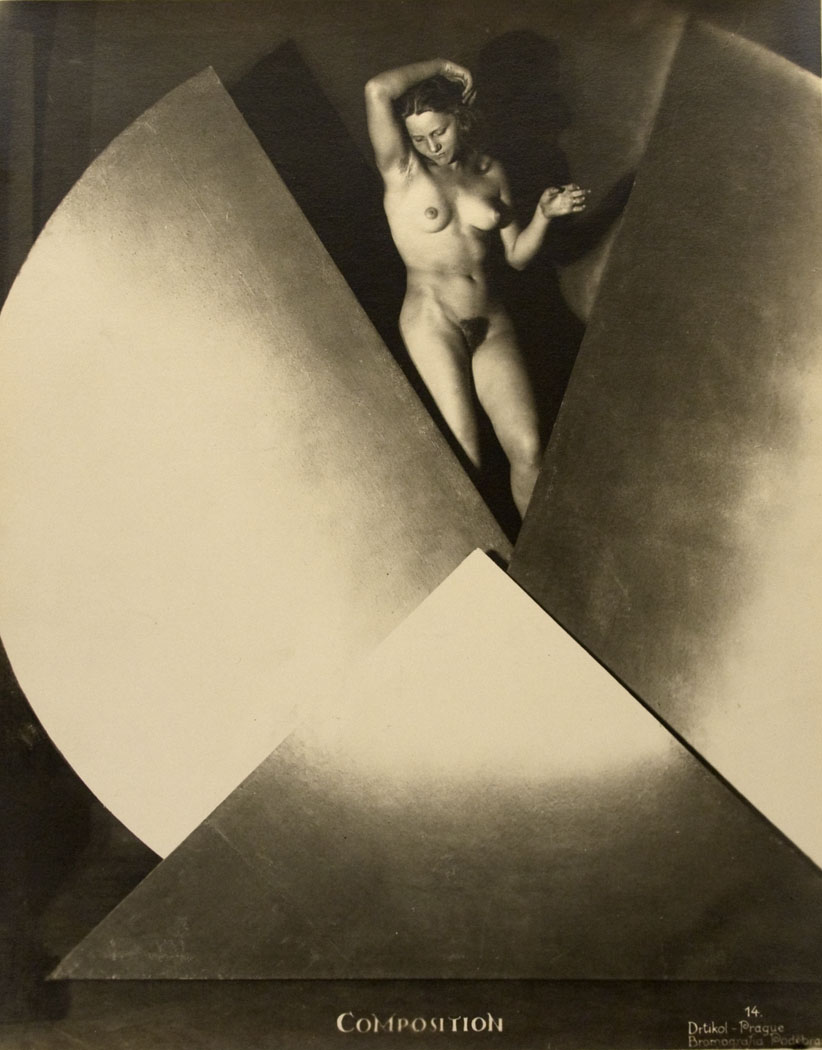

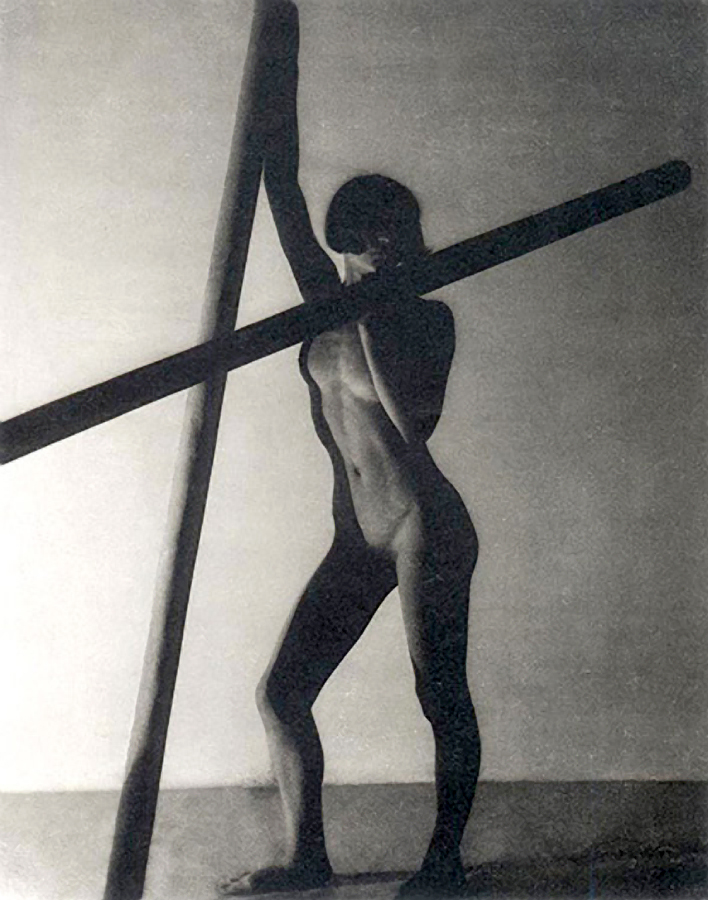

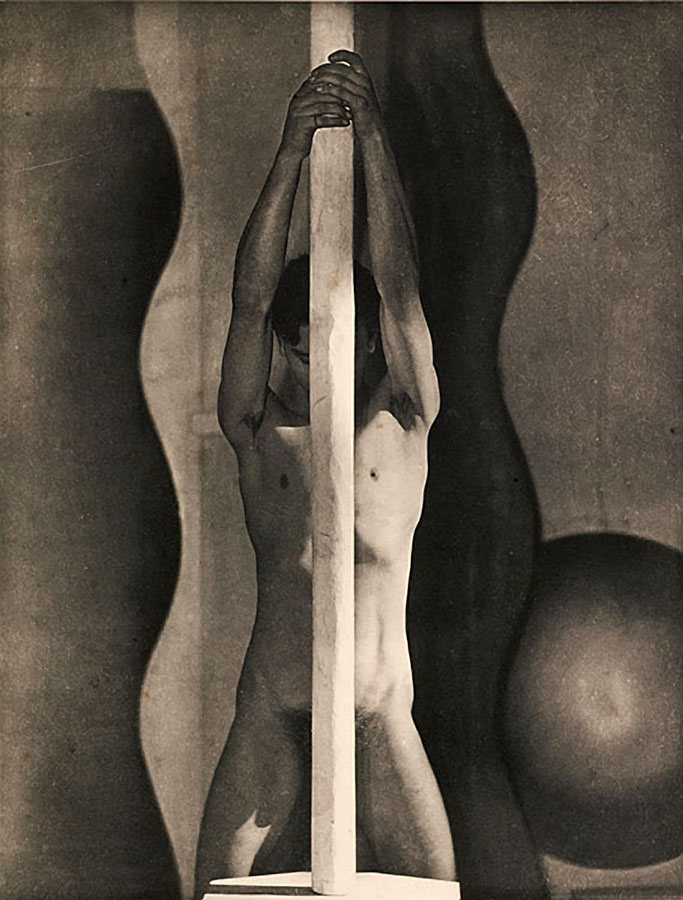

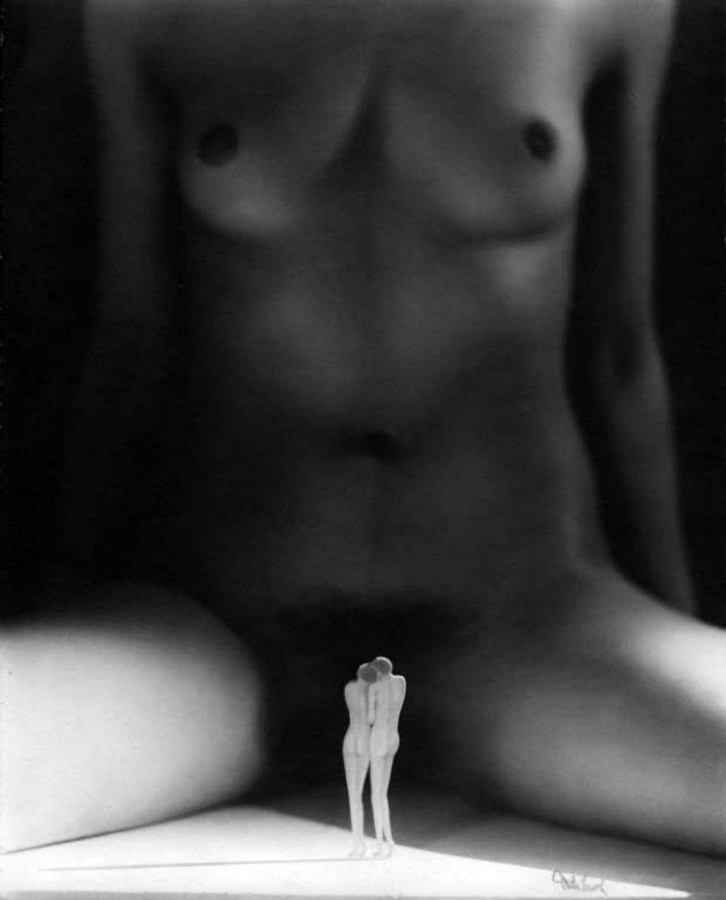

Also, while Art Nouveau had philosophical intentions, Art Deco was purely decorative. Drtikol was among the first photographers to incorporate the elements of Deco into his work, contrasting the suppleness and flexibility of the female body against solid and unyielding geometric forms while emphasizing the strength in both forms, human and geometric. It’s never clear whether the geometry is echoing the body, or the body is echoing the geometry: the implied motion of the body is, perhaps, the characteristic that most distinguishes one form from the other.

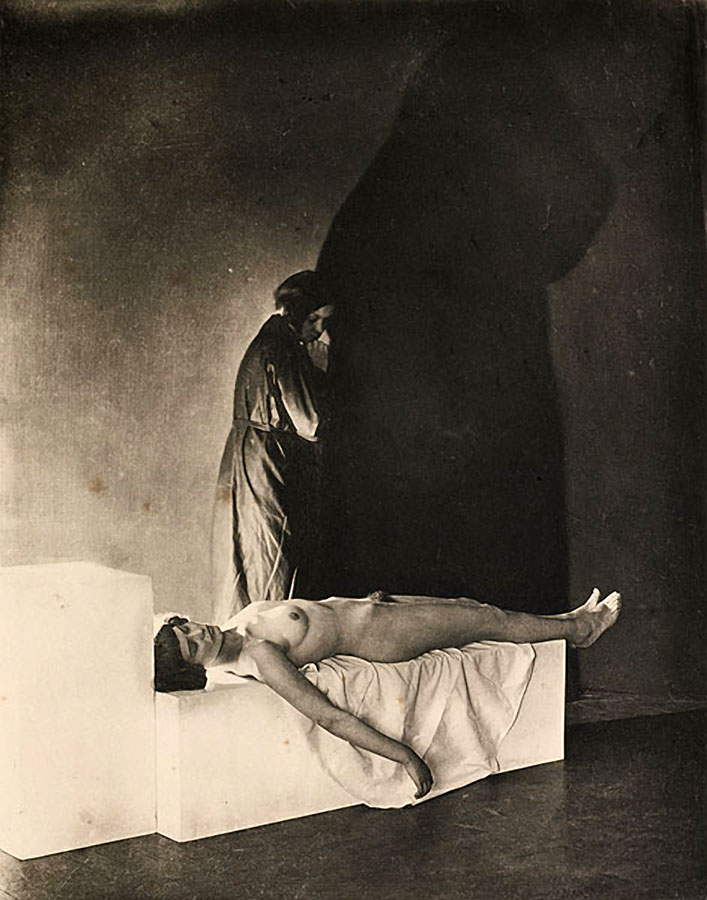

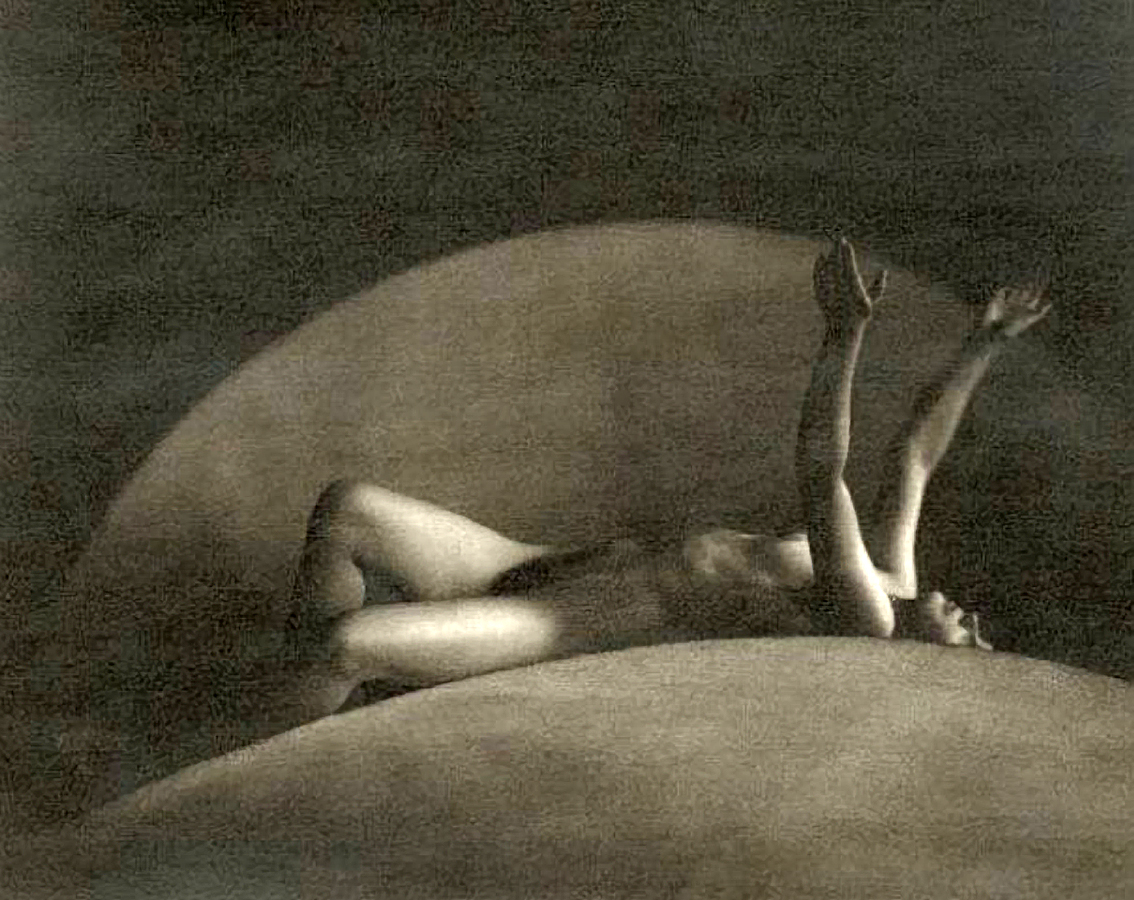

But retaining some of the Nouveau philosophy he still incorporated anything that could strengthen his compositions; besides the inclusion of Art Deco forms he borrowed the lighting techniques developed for the new moving pictures and integrated elements of expressive dance. He synthesized the modern and the classical, and the results were startling. Drtikol’s approach essentially transformed the genre: most artists working in nude studies had concentrated on the body, but for Drtikol the nude became only one element of the piece: it had to work in coordination with the other elements of the composition.

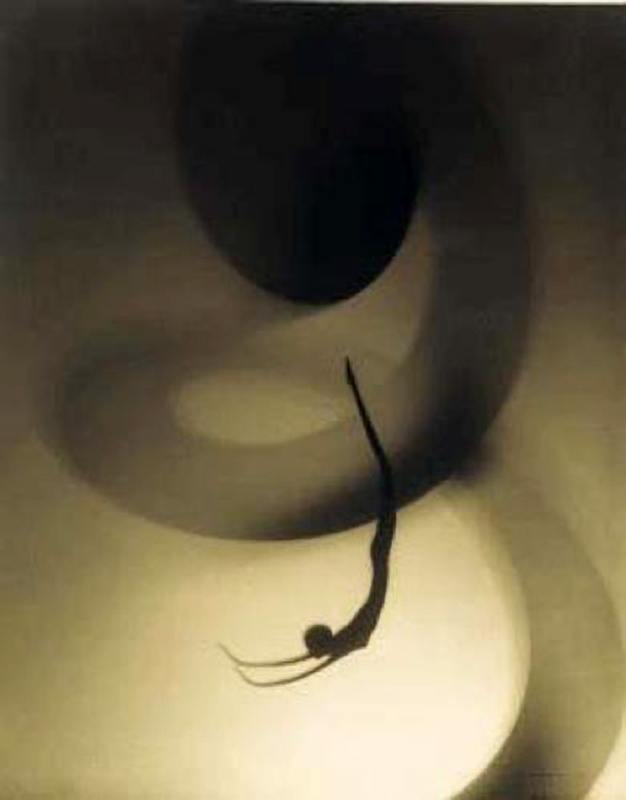

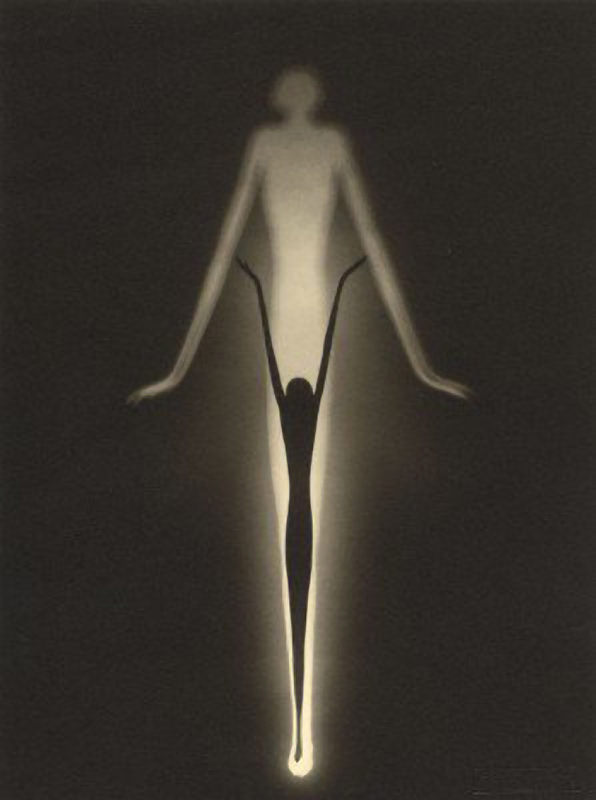

Eventually Drtikol decided that even the human body wasn’t malleable enough, and in 1930 he began to eliminate live models from his work, cutting forms out of stiff paper and shaping his compositions around those. Around this same time Drtikol became intrigued by Buddhism thought and practices and with the combined shift in his philosophy and the freedom that came from abandoning live models his work took on a more spiritual and ephemeral quality. Many critics also feel the work became more erotic as it became more abstract. Drtikol himself remarked that for the first time he was truly happy with his photography. In the 1920s and 1930s, Drtikol received significant awards at international photo salons.

That happiness lasted a mere five years: in 1935 Drtikol abruptly and without explanation stopped shooting photographs. The worldwide economic depression of that era and perhaps a spiritual movement towards a less material existence may have had an influence in his decision to close his Prague studio and sell all his prints, negatives and glass plates but for some reason he decided to begin painting again. In 1945 Drtikol taught photography at The State School of Graphic Arts in Prague, but resigned after one year: although he occasionally gave lectures Drtikol never again took up the camera. He gradually drifted into obscurity and his work fell out of fashion: by the 1950’s František Drtikol was essentially a hermit.

František Drtikol died in Prague on January 13, 1961. He is buried in the cemetery of Příbram, his hometown.

References:

http://www.skjstudio.com/drtikol/index.html

http://weimarart.blogspot.com/2010/10/nudes-of-drtikol.html