“Everything is permissible as long as it is fantastic.”

Born May 6, 1905 in Turin, Italy- Carlo Mollino was the son of an engineer. He studied at the Polytechnic in Turin, and began his own career in 1930 designing a house in Forte dei Marmi which won the G. Pistono prize for architecture. From 1933 to 1973 he only actually finished ten architectural works, but they were remarkable buildings for their time; the Società Ippica Torinese (1937–1940, demolished 1960), the building for the Slittovia di Lago Nero (1946-1947) and the Teatro Regio in Turin (1965-1973), the interior of which Mollino described as “a shape somewhere between an egg and a half-open oyster”.

Teatro Regio, Turin, 1965

Mollino was an avid skier, race driver and pilot. In the period between

the two wars he found himself at the center in the lively ‘second

Futurism’ cultural environment in Turin, where he associated with many

of the icons in the world of culture and art: among his early influences

was a close friendship with the painter and scholar Italo Cremona.

Besides architecture he turned his focus to interior and furniture

design.

In 1936 he began Casa Miller, his first rental – a small,

apparently windowless space on the second floor of a new development on

Via Talucchi named after Alfonsina Miller, a ghostly character in his

novel L’amante del duca, which he had published as a serial a few years earlier. In Casa Miller Mollino established a private world that he would maintain throughout his life.

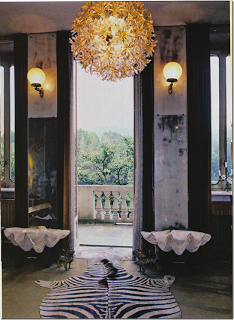

Casa Miller, Turin

In 1955 Mollino entered the Le Mans 24-hour Endurance Race with the Bisiluro (“Twin Torpedo”), an asymmetrical, ultra-light, aerodynamic design created by himself and Enrico Nardi.With the engine mounted on the left hand side (to counter the weight of the

driver, seated on the right) the total weight of the car is just 450kgs

(992lbs) and it’s twin cam 4 cylinder, 737 cc Gianni engine was said

to produce 62hp. Unfortunately the Bisiluro

was literally blown off the track by the vortex kicked up by a

close-passing D-Type Jaguar and sustained too much damage to continue

the race.

Mollino had a lifelong fascination with the occult and esoterica; he accrued

a massive collection of material on astrology, clairvoyance,

radiesthesia, magic, yoga and secret rituals and wrote about astrology

under the pseudonym Carlo Bertolino. Although he was always

known for his use of strange and singular color combinations; malachite

and silver, bright red and lavender – the themes actually derived

from his research in radiesthesia, a

parapsychological practice of detecting and interpreting various

radiations emitted by our bodies. Mollino developed a color wheel that

correlated 18 colors with various emotions, and used it extensively through all his design work.

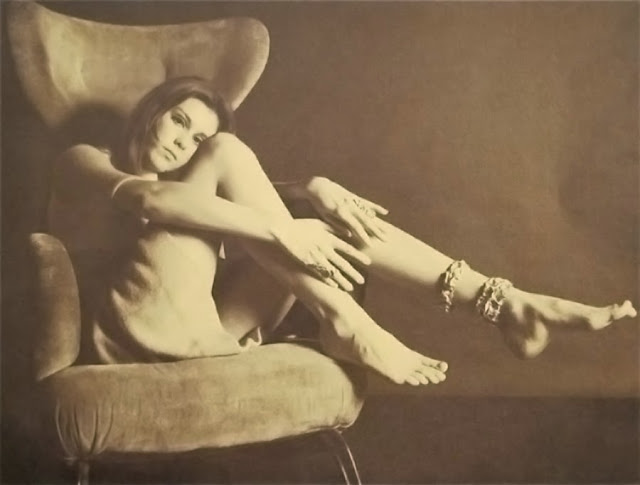

Photography was another common denominator in Mollino’s manifold creative repertoire. It encompasses his architectural articles published in Casabella,

Domus and Stile magazines and his sensually designed chairs. Mollino published several books of his own photography, as well as producing Messaggio dalla camera oscura

(Message from the Darkroom, 1949), an ambitious compendium retracing

the history of photography from daguerreotypes to Richard Avedon, via

the Surrealists.

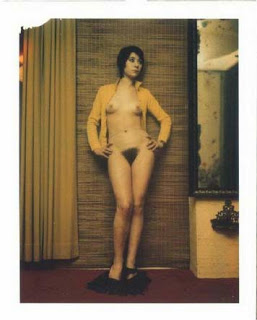

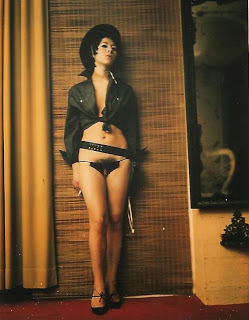

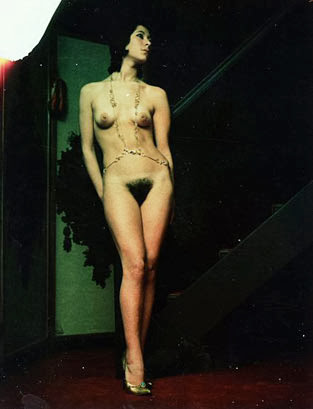

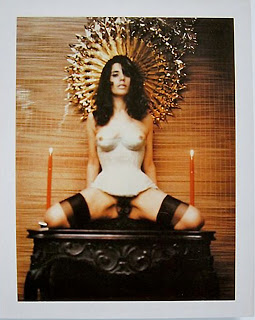

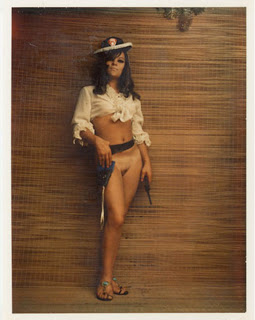

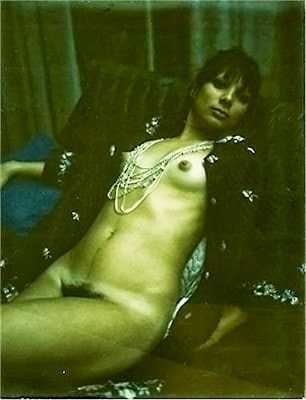

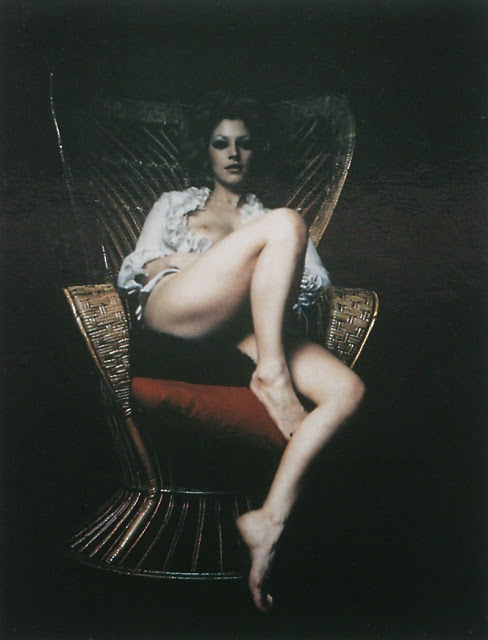

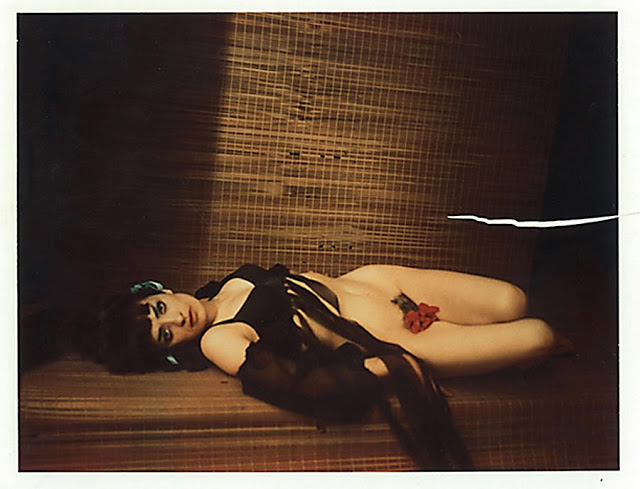

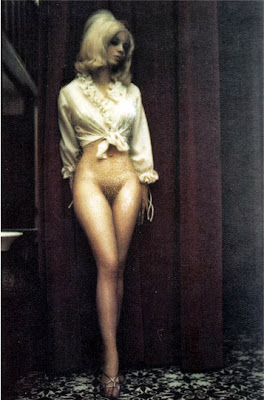

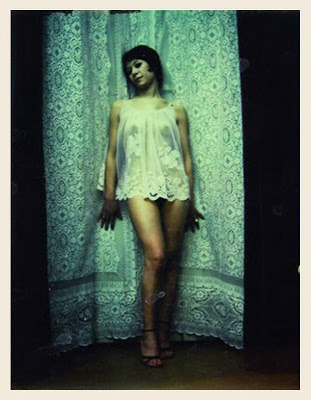

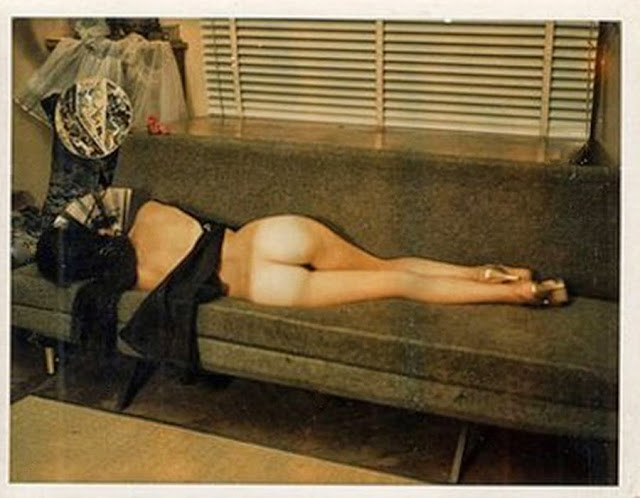

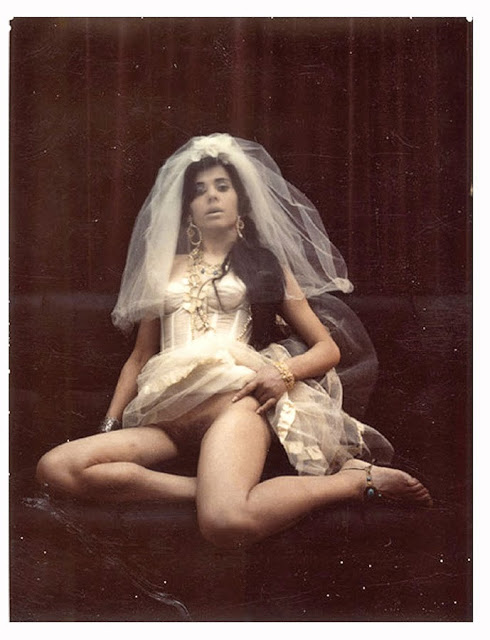

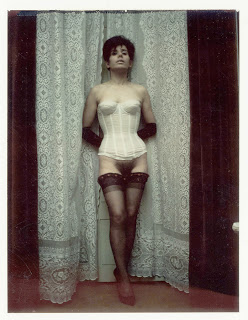

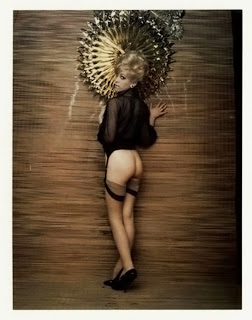

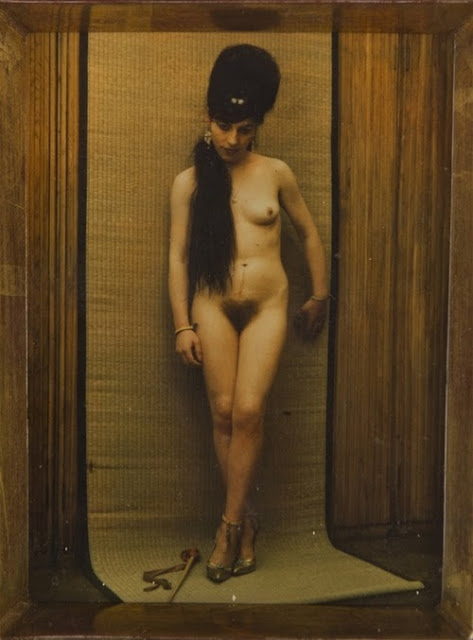

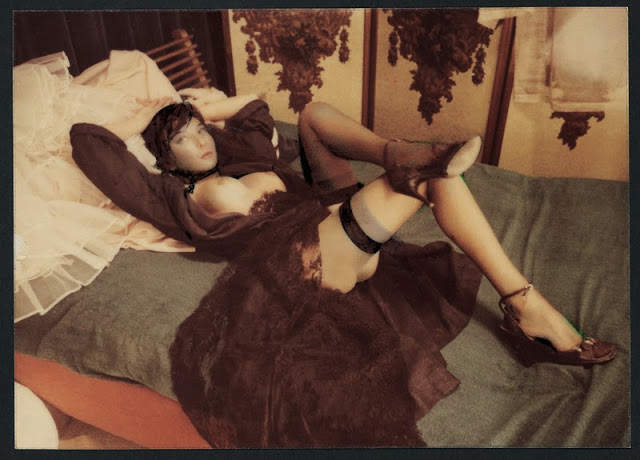

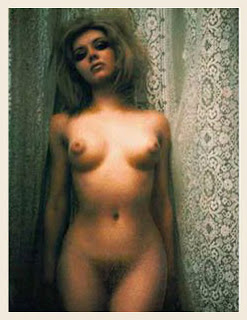

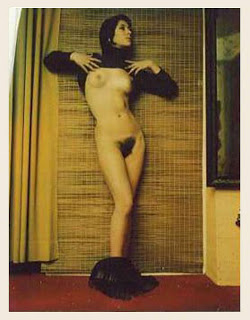

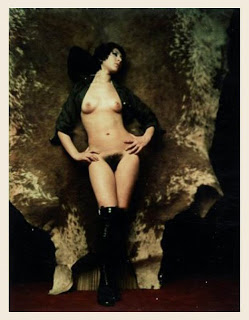

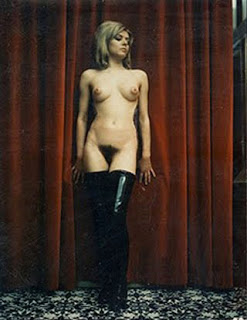

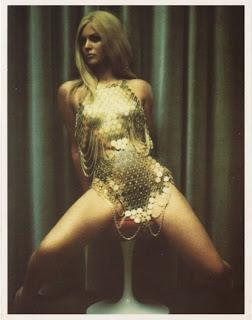

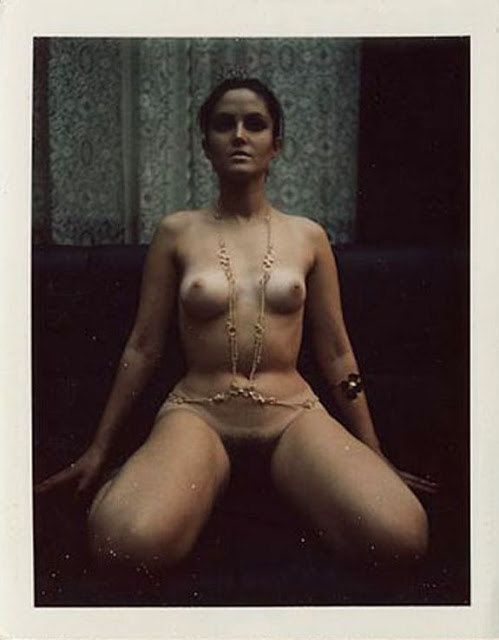

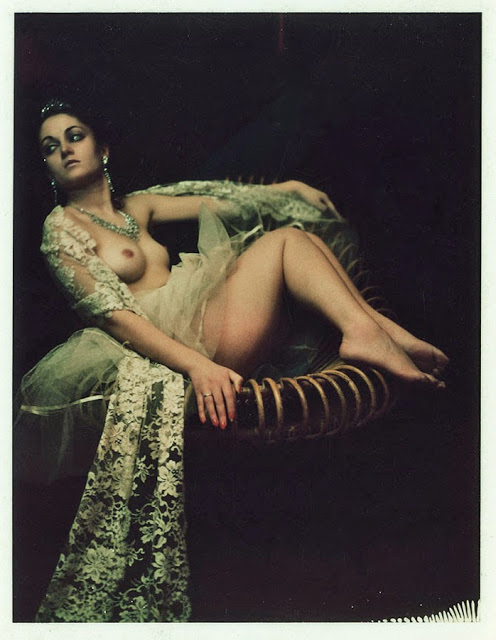

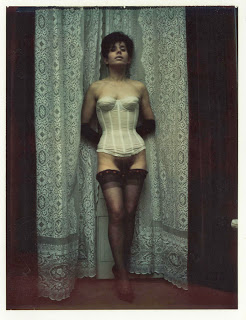

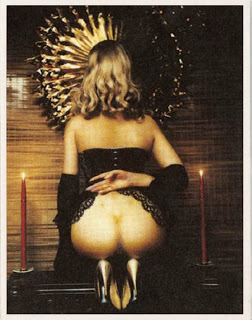

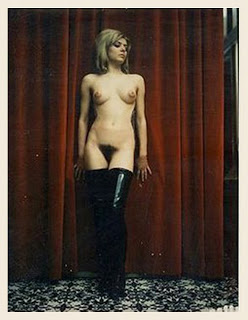

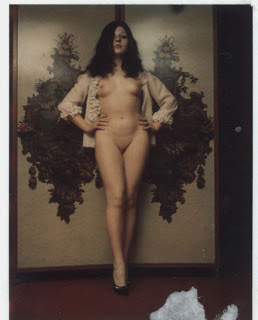

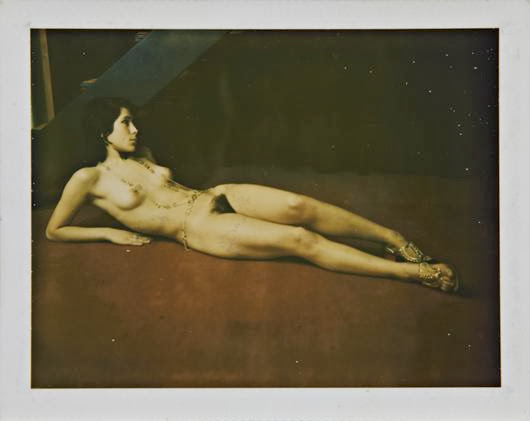

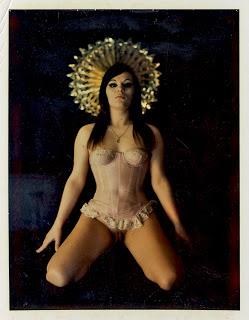

In 1960

Mollino took possession of a two-story villa which he named Villa Zaira, a tribute to a rebellious female

cousin. He never spent a single

night there. To friends or colleagues, the villa was likely a

combination workshop and storage facility, a place away from the

luxurious apartment he shared with his devoted housekeeper but reportedly he never actually stayed there: instead he turned it into a studio where he photographed a variety of women, mostly believed to be prostitutes. After Mollino’s death in 1973 executors found an antique cabinet in his

home filled with carefully filed envelopes containing more than 2,000 Polaroid photographs of women preserved on cardboard backing and

slathered with the lacquer that Polaroid recommended in those days to

keep pictures from fading.

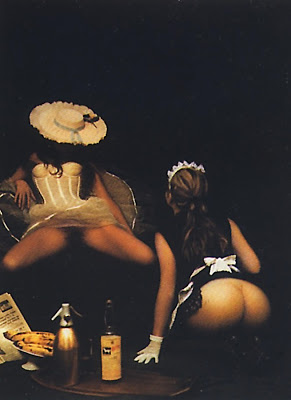

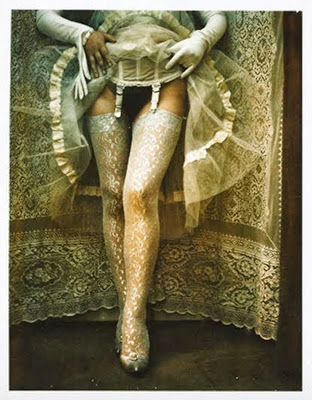

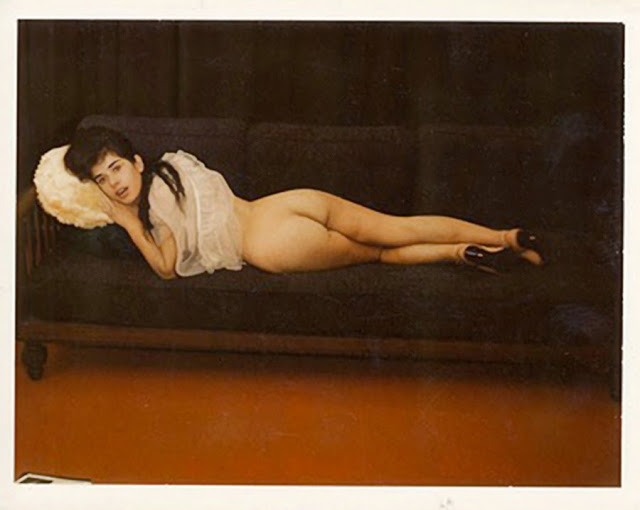

The scenes were carefully prepared: the models would dress (or partially

undress) in costumes, accessories and wigs that Mollino had acquired on

trips to France or Southeast Asia, and pose before backdrops of

drapery, screens and sculptural furniture. Despite the furtive

circumstances of their production, these portraits express the

aesthetics of Mollino’s more public photographs, as the models appear

more statuesque than pornographic.

More :

Domus: Mollino’s Casa Miller

salon.com; Smile, you’re on carnal camera

nytimes: Carlo Mollino’s Seductive Allure

Domus: The Asymmetric Racer