George Hendrik Breitner

George Hendrik Breitner was born in Rotterdam in 1857. He enrolled in the Art Academy in The Hague in 1876, later working as an art teacher at the Leiden academy Ars Aemula Naturae. Expelled from the academy in 1880 for misconduct, he moved into landscape artist Willem Maris’s studio; during this period he was accepted into the Dutch art society, institution and studio Pulchri and worked on the

Panorama Mesdag. But Breitner felt restricted by the Hague School, and gradually distanced himself from it as he leaned further towards the growing impressionist movement. He preferred working-class models: laborers, servant girls and people from lower-class neighborhoods; he saw himself as ‘le peintre du peuple’, the people’s painter. He soon developed an association with the Dutch Tachtigers (“Eighty-ers”) literary group that championed impressionism and naturalism against romanticism.

Conservative critics called Breitner’s style ‘unfinished’.

In the early months of 1882, Breitner came into contact with Vincent van Gogh, who was introduced by his brother Theo. The pair sketched together in the working-class districts of The Hague; Breitner was motivated to do so because he regarded himself as a painter of the common folk, while Van Gogh was more intent on recruiting models. It is likely that Breitner introduced van Gogh to the novels of Émile Zola and the cause of social realism.

Breitner was hospitalised in April. Van Gogh visited him in hospital, but Breitner did not return the visits when van Gogh himself was hospitalised two months later and they did not meet again until the following July when van Gogh was on the verge of leaving The Hague and Breitner spending more time in Rotterdam. van Gogh gave Theo a less than flattering account of Breitner’s paintings as resembling mouldy wallpaper, although he did say he thought he would be all right in the end.

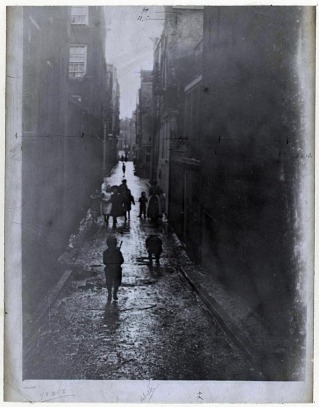

In 1886, Breitner moved to Amsterdam and entered the Rijksakademie, but it was quickly apparent that he was “…far beyond the level of education offered there.” He recorded the life of the city in sketches, paintings and photos, sometimes creating several pictures of the same subject from different angles or in different weather conditions.

Two years after van Gogh’s death, Breitner wrote that he did not like van Gogh’s paintings:”‘I can’t help it, but to me it seems like art for Eskimos, I cannot enjoy it. I honestly find it coarse and distasteful, without any distinction, and what’s more, he has stolen it all from Millet and others.”

By 1890, cameras became affordable, and Breitner saw photography as a much better instrument to satisfy his ambitions. He became very interested in the movement and illumination in Amsterdam and soon mastered the new medium: today he is often referred to as one of the early pioneers of “street photography”. His preference for cloudy weather conditions and his muted grey and brown palette likely resulted from his focus on photography. It has sometimes been assumed that Breitner took photographs simply as studies for his paintings, but most of the pictures have no bearing on his other works.

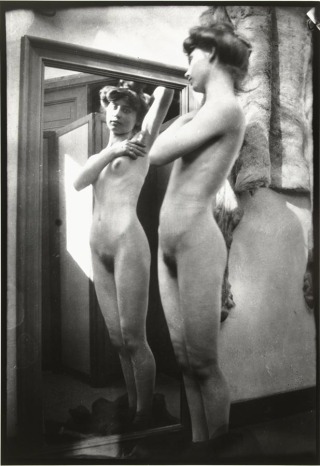

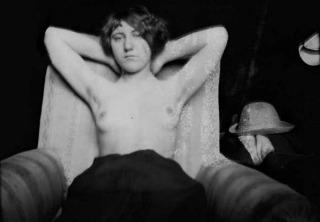

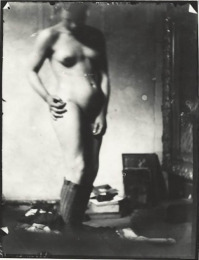

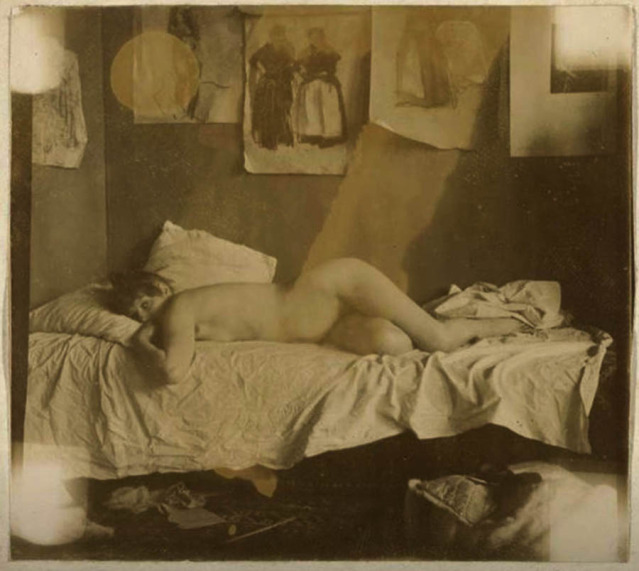

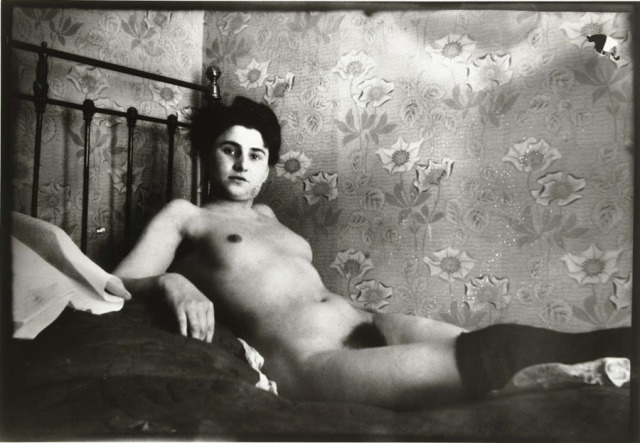

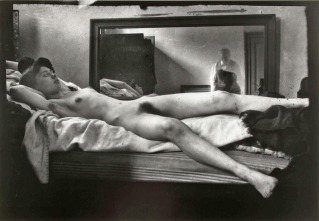

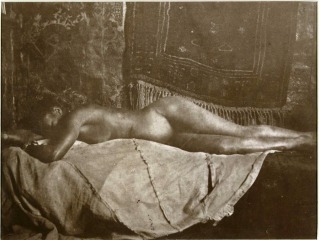

He often painted female nudes, but was criticized for painting them too realistically and the critics felt they “…did not resemble the common ideal of beauty”. In his own time Breitner’s paintings were admired by artists and art lovers, but often despised by the Dutch art critics for their raw and realistic nature.

Similarly, he photographed several nude models; the motivation behind these pictures is obvious, and they lack the exploratory impulse of the photographs taken outside. One author states that “Free of classical or other narrative associations, these images were not intended to signal anything other than a specific desirable body in a particular room.”

Breitner rarely commented on his photography. In his circles it was frowned upon for artists to use photographs; the painter’s observation and invention were much more highly valued than the use of a camera as mechanical drawing aid. In his book Korte geschiedenis der Hollandsche schilderkunst (a brief history of Dutch painting), published the year Breitner died, the prominent critic Albert Plasschaert wrote about Breitner’s art: “…in addition I believe that I can detect here and there the use of a camera (that danger).”

Breitner rarely commented on his photography. In his circles it was frowned upon for artists to use photographs; the painter’s observation and invention were much more highly valued than the use of a camera as mechanical drawing aid. In his book Korte geschiedenis der Hollandsche schilderkunst (a brief history of Dutch painting), published the year Breitner died, the prominent critic Albert Plasschaert wrote about Breitner’s art: “…in addition I believe that I can detect here and there the use of a camera (that danger).”

In fact the discovery that Breitner had been such a prolific photographer would only come 40 years after his death. In 1961 the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague received almost 2,000 negatives and 300 prints from Hein Siedenburg, the heir of the art gallery that represented Breitner in his final years.

By the time Breitner’s photographic activities actually became public the use of photography by painters was much more favorably regarded, and comments in the press were on the whole positive. If Breitner was concerned about the effect on his posthumous reputation, then it is likely that the negatives and prints were made public only after they no longer posed a threat to his status as a painter.

Since that time several more groups of Breitner’s negatives and prints have surfaced. Approximately 2,850 negatives and prints are currently known, and of these three quarters are in the collection of the RKD. The remaining groups are housed in Leiden University Library, Amsterdam City Archives and the Rijksmuseum.

Breitner’s photographs continue to intrigue us to this day, 50 years since they were first discovered. Their number and diversity is so great that new insights can still be made and much remains to be said about his reasons for producing them, his motives for using them as well as his ‘manipulation’ of the photographic medium.

By the turn of the century Breitner was famous in the Netherlands, and had a highly successful retrospective exhibition at Arti et Amicitiae in Amsterdam (1901). He traveled frequently in the last decades of his life, visiting Paris, London, and Berlin, and he continued to take photographs. In 1909 he went to the United States as a member of the jury for the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh.

But although Breitner exhibited abroad early on, his fame never crossed the borders of the Netherlands. At the time foreign interest was focused more on anecdotal and picturesque works; as time went by critics lost interest in Breitner, and the younger generation regarded impressionism as too superficial. By 1911 all the latest art movements arrived in the Netherlands one after another including cubism, futurism and expressionism. Breitner’s role as contemporary historical painter was finished.

Although Breitner kept his distance from younger generations and his work was judged more critically after 1900, he did not sink into oblivion. In 1917 a relief committee was set up to help him deal with financial problems, soon raising about 60,000 guilders. Breitner certainly struggled with finances all his life, and a large proportion of his letters deal with money matters.

George Hendrik Breitner died on 5 June 1923 in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

References:

George Hendrik Breitner, General-books.net

Second Sight: The Photographs of George Hendrik Breitner

Rijksmuseum.nl

George Hendrik Breitner: the photographer

Comments

George Hendrik Breitner — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>