The Sun Between the Storms; Part III, Paris

|

| “Picasso and fellow artists“, Jean Cocteau |

An Odyssey of the 1920’s: Les Années Folles

The romance of Paris, especially in that period between the two world wars, continues to resonate with many people around the globe. The city has seen many “golden ages” but probably none as famous as les Années Folles, or “the mad years” of the 1920s. Paris was at the center of it all, not only in terms of fashion and entertainment but in the domains of art and architecture.

The romance of Paris, especially in that period between the two world wars, continues to resonate with many people around the globe. The city has seen many “golden ages” but probably none as famous as les Années Folles, or “the mad years” of the 1920s. Paris was at the center of it all, not only in terms of fashion and entertainment but in the domains of art and architecture.Paris was the cultural center of Europe in the 1920s. The disillusioned came there, as did the unemployed, the artistic, the unusual. It was the headquarters of the Lost Generation and the avant-garde; Dada and the Surrealists, a new wave of expressionists and cubists.

France had a self-sufficient economy; founded on small and medium-sized businesses rather than shares, the French put their confidence in gold. Investments abroad were numerous.

|

| “J’accuse“, Abel Gance |

The German reparations decided by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919

brought in large amounts of money which served principally to repay war

loans to the United States. Full employment meant that public confidence

in the government was high. But although France had come out of World

War I a victor, she was

exhausted. The Eastern parts of the country were devastated: her

casualties in the war had also been higher than those of the other

Allied nations. France had 1,322,000 killed and three million wounded in

the war, with a quarter of her dead being young men under 24.

Yet this intense personal loss coupled with an economic boon unparalleled in Europe at the time undoubtedly played a part in creating the unique situation in which the arts were able to flourish. Anyone could afford to live in Paris, and almost anyone could make some kind of money there. It became a magnet for the displaced, ragtag youth of that era.

|

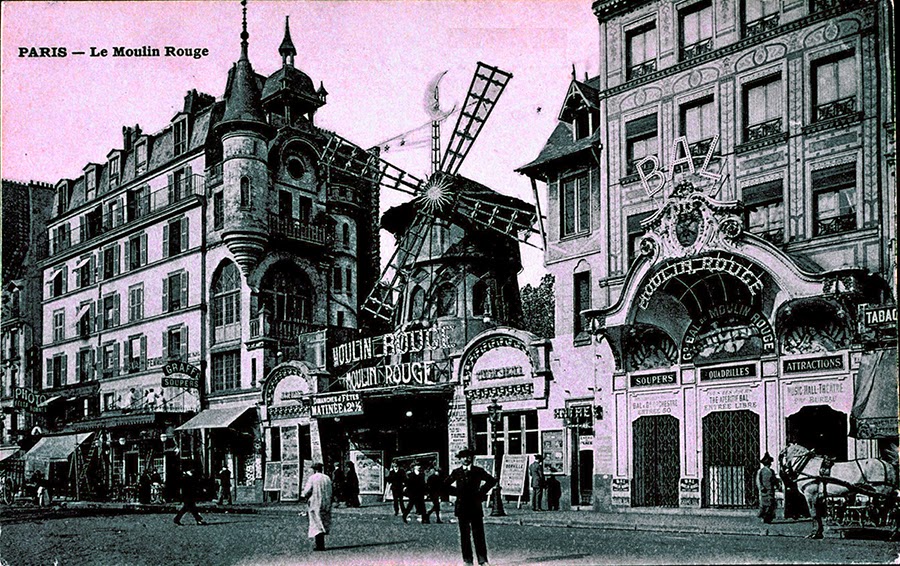

| Moulin Rouge, Montmarte district, 1900 |

Since the end of the 19th century the northern, right bank district of Montmartre in Paris (18th arrondissement) had been the intellectual and creative center for the “Bohemian culture”. Montmarte was outside the city limits; free of Paris taxes the neighborhood featured cheap rents and cheap booze, and became famous for its cabarets such as the Moulin Rouge and Le Chat Noir. In an earlier generation Montmarte had been home to Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec among others. Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and other impoverished artists had lived and worked in the commune Le Bateau-Lavoir prior to the war.

That earlier Montmartre circle represented a group assembled more on the basis of status affinity than artistic tastes; the new post-war intellectuals were in much the same economic and social spectrum. But Paris and its landscape had changed in the early 20s; Montmartre was now a famous tourist destination and the city fathers intended to redevelop the old neighborhoods in order to cash in on that. The quaint wooden houses, the windmills and the green spaces were being replaced with modern concrete apartment buildings, skyscrapers and shopping centers designed to take full advantage of the burgeoning economy. As rents and taxes rose the remains of the artist community staged protests, but to little avail. A victim of its own popularity, the art scene had to move.

|

| Left bank, Montparnasse district |

Although some of the more affluent artists of Paris remained in Montmartre, the left bank district of Montparnasse (14th arrondissement) became famous in the 1920s as the new heart of intellectual and artistic life in Paris. Montparnasse was a place for the gritty, die-hard emigrant artist; virtually penniless painters, sculptors, writers, poets and composers began to drift in from around the world, drawn by the creative atmosphere and the cheap rent in artist communes. Living without running water, in damp, unheated “studios” usually shared with rats, most of them sold their work just to buy food. Although Jean Cocteau once said that poverty was a luxury in Montparnasse, Fernand Léger wrote of that period: “ man…relaxes and recaptures his taste for life, his frenzy to dance, to spend money…an explosion of life-force fills the world.”

Montparnasse was a community where creativity was embraced with all its oddities, each new arrival welcomed unreservedly by its existing members.

“I aspired to see with my own eyes what I had heard of from so far away: this revolution of the eye, this rotation of colours, which spontaneously and astutely merge with one another in a flow of conceived lines. That could not be seen in my town. The sun of Art then shone only on Paris.” -Marc Chagall

|

| Above: La Ruche commune, photographs from 1910’s – modern. |

Located in the “Passage Dantzig,” La Ruche (the Beehive) was an old three-story circular structure that was originally designed by Gustave Eiffel for use as a wine rotunda at the Great Exposition of 1900. It was dismantled and re-erected as low-cost studios for artists by Alfred Boucher in 1902 in an attempt to provide young artists with dirt-cheap housing, shared models and exhibition space. La Ruche also became a home to the usual array of drunks, misfits, and almost every penniless soul needing a roof over their head.

The Russian painter Pinchus Kremegne reportedly got off the train at the Gare de l’Est with three rubles in his pocket; the only words in French he knew was the phrase “Passage Dantzig”; but that was all he needed to get him there. Few places have ever housed such artistic talent as could be found at La Ruche.

|

| “Female Nude“, Salvadore Dali 1926 |

Many of those painters and sculptors went on from their humble roots in Montparnasse to achieve international fame; Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, and Salvador Dalí among others have names instantly recognizable today. Yet there were many others who, despite being equally talented, failed to garner such attention.

|

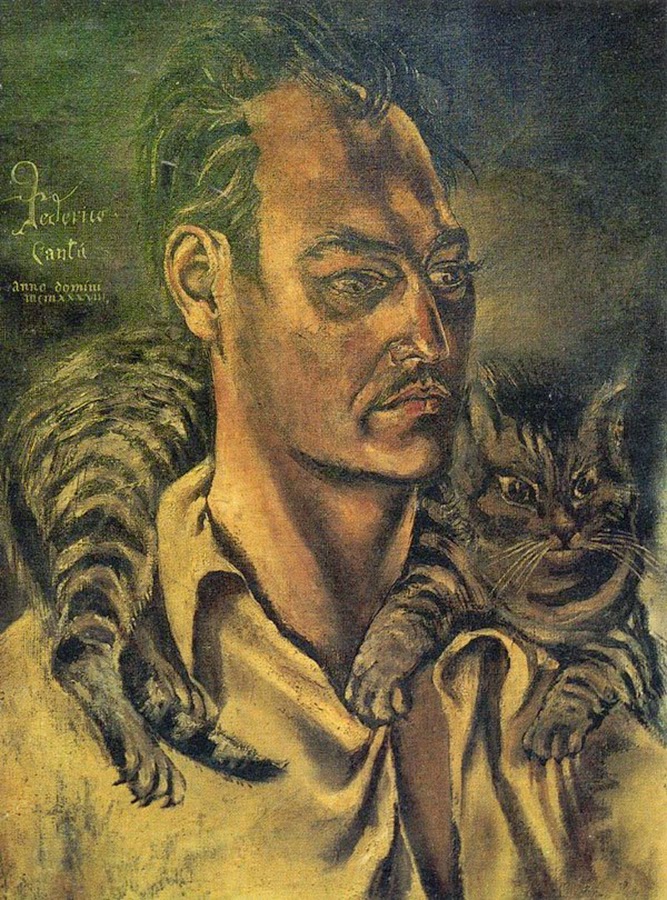

| “Self Portrait with Cat“, Federico Cantú |

The Russian painter Chaim Soutine had lived at La Ruche during the war. In 1923 a prominent American collector bought 60 of his paintings on the spot. Soutine had been virtually penniless throughout his years in Paris; he immediately took the money and hailed a taxi, ordering the driver to take him to Nice more than 400 miles away. Another story about Soutine tells how he horrified his neighbours by keeping an animal carcass he was painting. The stench drove them to send for the police, who were sharply lectured on the relative importance of art over hygiene. Marc Chagall reportedly saw the blood from the carcass leaking into the corridor outside Soutine’s studio, and rushed out into the street screaming, “Someone has killed Soutine!”

The Mexican painter, engraver and sculptor Federico Cantú Garza went to live in Paris on Rue Delambre in Montparnasse at the age of sixteen and created chests full of drawings which were later lost; although he gained fame as a muralist after returning to Mexico in the ’30s, most of his work from the Montparnasse years is forgotten.

Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși was invited to enter the workshop of Auguste Rodin, but left the studio after only two months saying “…nothing can grow under big trees.” In 1920 he developed a notorious reputation with the entry of “Princess X” in the Salon; the phallic shape of the piece was deemed scandalous, and despite Brâncuși’s explanation that it was an anonymous portrait it was removed from the exhibition. He later began a group of sculptures known as “Bird in Space”, simple shapes representing a bird in flight. The works are based on his earlier “Măiastra” series; in Romanian folklore the Măiastra is a beautiful golden bird who foretells the future and cures the blind. Over the following 20 years, Brâncuși would produce some 20 versions in marble or bronze.

Spanish sculptor Julio Gonzalez associated with the Spanish circle of artists in Montmartre, including Pablo Gargallo, Juan Gris and Max Jacob. In 1918 he developed an interest in the artistic possibilities of welding, after learning the technique in the Renault factory at Boulogne-Billancourt. This technique would subsequently become his principal contribution to sculpture, though he also painted and created jewellery. In 1920 he provided technical assistance in executing Picasso’s sculptures in steel: he also forged the infrastructures of Constantin Brâncuși’s plasters. In the winter of 1927-28, Gonzalez taught Picasso oxy-acytelene welding and cutting techniques and from October 1928 until 1932 both men worked together. By 1932, González was the only artist with whom Picasso shared his personal studio.

|

| Alberto Giacometti |

|

| “Nudo con due Maschere“, Marie Vassilieff |

|

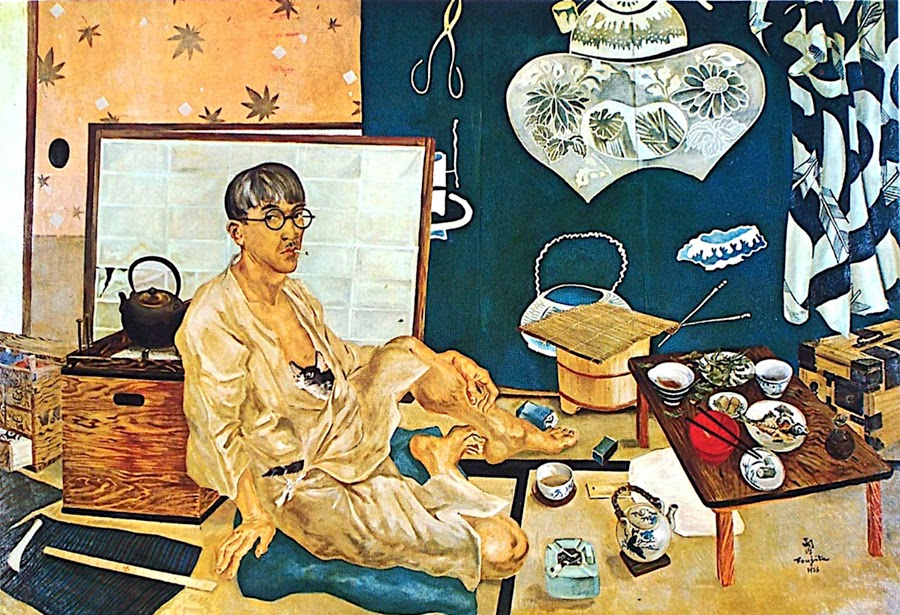

| “Autoportrait“, Tsuguharu Foujita |

|

| “Cat Fight“, Tsuguharu Foujita |

|

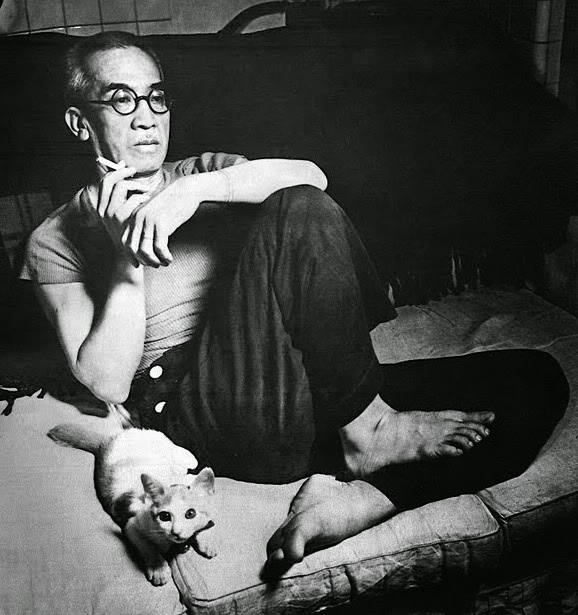

| “Leonard” Tsuguharu Foujita |

In 1922 Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti moved to Paris to study under the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, an associate of Auguste Rodin. It was there that Giacometti experimented with cubism and surrealism and came to be regarded as one of the leading surrealist sculptors.

Hilaire Hiler, an American expatriate living in Paris in the 1920s, occupied himself painting interior murals and performing jazz piano with his pet monkey.

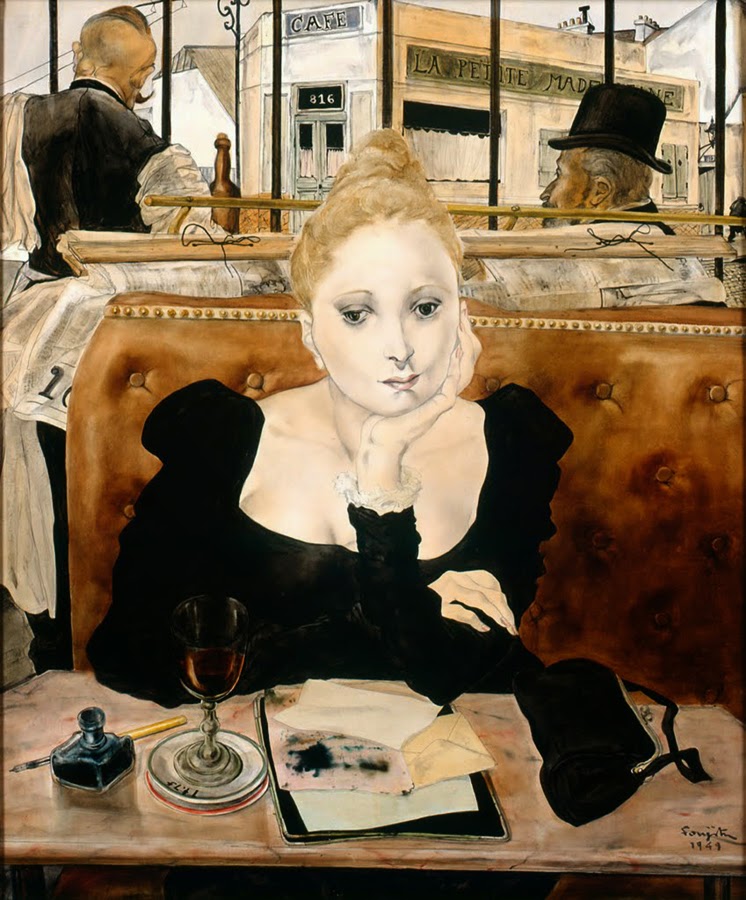

The Japanese printmaker and painter Tsuguharu Foujita arrived in 1913 and was one of the few Montparnasse artists who made any real money in his early years; by 1925 Foujita had received the Belgian Order of Leopold and the French Legion of Honor.

Russian born Marie Vassilieff had moved to Paris in 1907 at the age of twenty-three and became an integral part of the artistic community of Montparnasse; Vassilieff is most remembered for her canteen that provided a full meal and a glass of wine for only a few centimes. After Georges Braque had been wounded in the war and was released from service in 1917, Vassilieff and Max Jacob decided to organize a welcoming dinner. Among the guests was Beatrice Hastings, Amedeo Modigliani’s ex girlfriend, with her new boyfriend Alfredo Pina. Modigliani had a bad temper, especially when he was drinking, and Vassilieff specifically didn’t invite him to

Braque’s party. He showed up anyway, uninvited and very drunk,

looking for a fight. A scuffle ensued; a pistol

appeared, and Marie Vassilieff, all five feet of her, pushed Modigliani

down the stairs while Picasso and Manuel Ortiz de Zarate locked the door behind him.

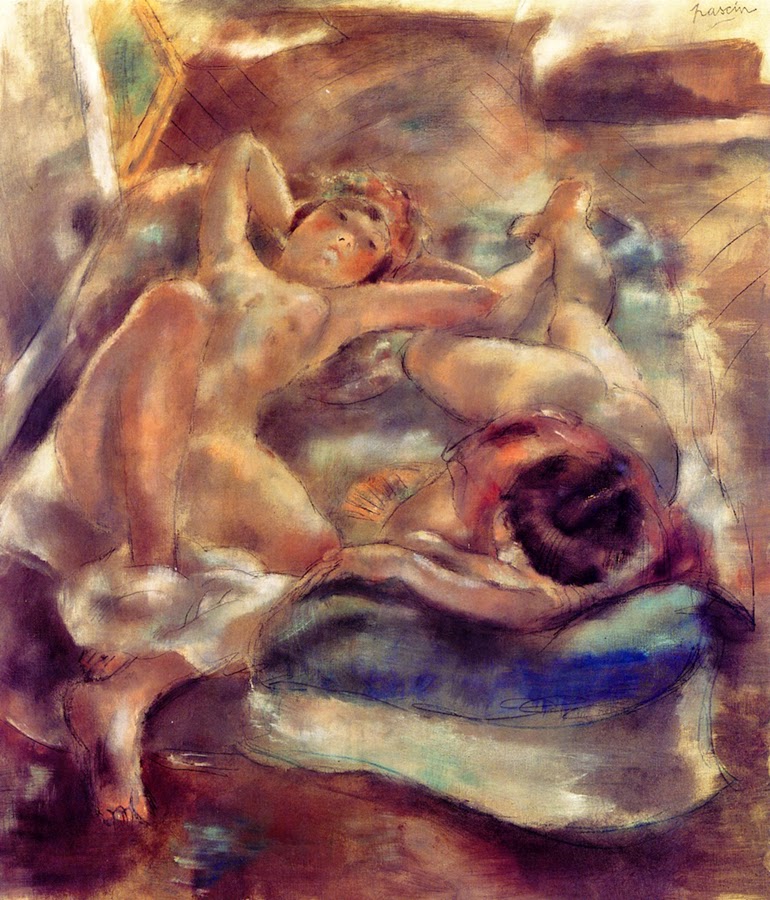

Jules Pascin: “Claudine Resting” “Two Reclining Nudes“

|

| “Nude Reading“, Jules Pascin |

|

| “Siesta“, Jules Pascin |

Jules Pascin was a painter born in Bulgaria. To avoid service in the Bulgarian army Pascin had traveled for a time in the United States, and became the symbol of the Montparnasse artistic community after moving there in 1920. During the 1920s Pascin mostly painted fragile petites filles, prostitutes waiting for clients, or models waiting for the sitting to end. His fleetingly rendered paintings sold readily but the money he made was quickly spent. Famous as the host of numerous large parties in his flat, whenever he was invited elsewhere for dinner he arrived with as many bottles of wine as he could carry.

Ernest Hemingway’s chapter “With Pascin At the Dôme” in A Moveable Feast recounted a night in 1923 when he had stopped off at Le Dôme and met Pascin escorted by two models: Hemingway’s portrayal of the evening is considered one of the defining images of Montparnasse at the time.

It should be noted that many of these artists had moved to Paris in the decades before Les Années Folles, and many of them produced their more remarkable works in the decades afterwards. But they were all nonetheless in and around the city throughout the 1920s, and they all contributed to the cultural atmosphere of the time.

“… if you want books written by ladies, here is a book written by a

woman who has never been at any time a lady writer; for ten years she

was, insofar as our time allows, called a queen. That is very different

of course than being a Lady.”

-Ernest Hemingway, on Kiki’s Memoirs

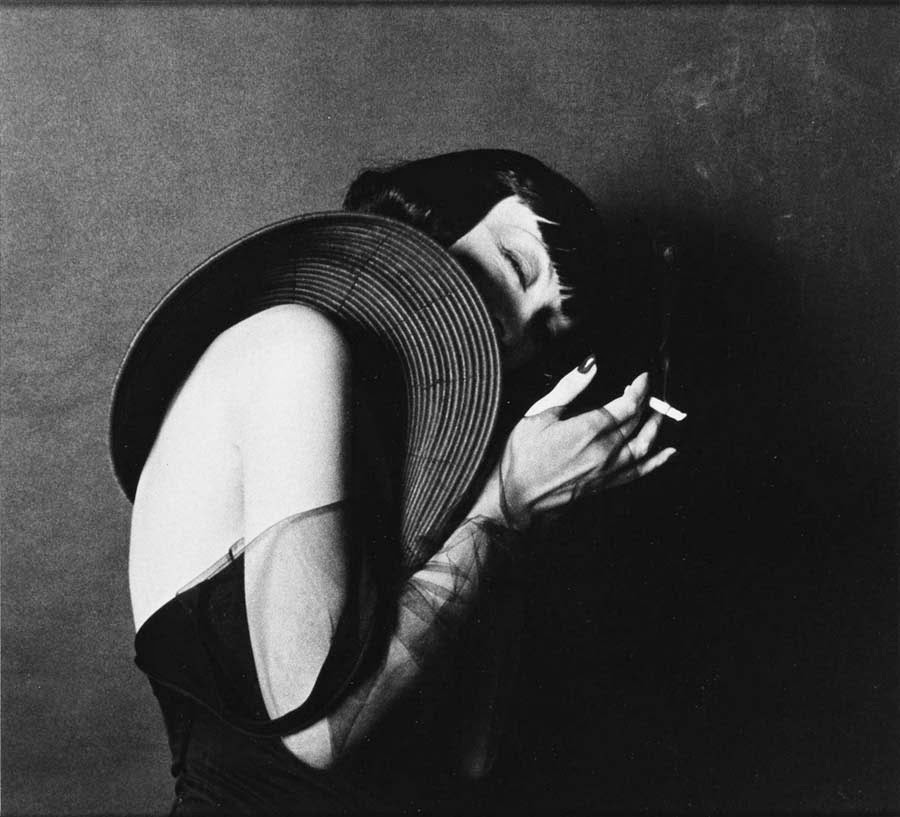

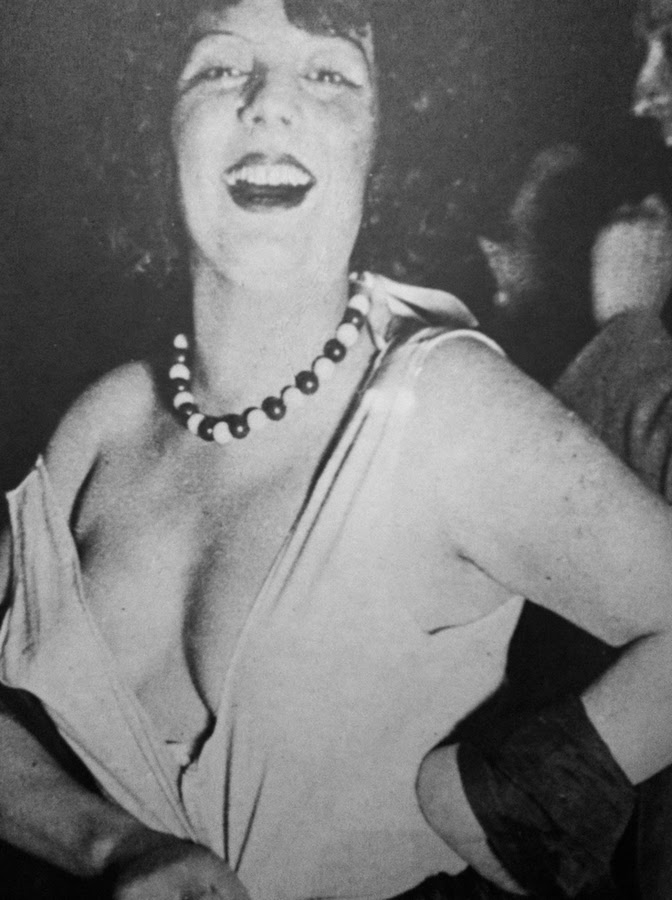

Alice Prin was born in 1901 in Châtillon-sur-Seine, Côte d’Or; an illegitimate child, she was raised by her grandmother in abject poverty. At age twelve she was sent to live with her mother in Paris in order to find work. She began working in shops and bakeries, but was posing nude for sculptors by the age of fourteen.

By the time she reached her twenties she was beautiful and street-smart. She had entered and left several abusive relationships, but around

this time Montparnasse became her spiritual and physical home. She adopted the

moniker “Kiki”, and remade herself as a model, muse, lover, cabaret

performer, and denizen of the legendary cafes and nightclubs of

Montparnasse. As she was to write later, “I

had found my true milieu! The painters adopted me. End of sadnesses.

I still often went hungry, but the good fun made me forget all that.”

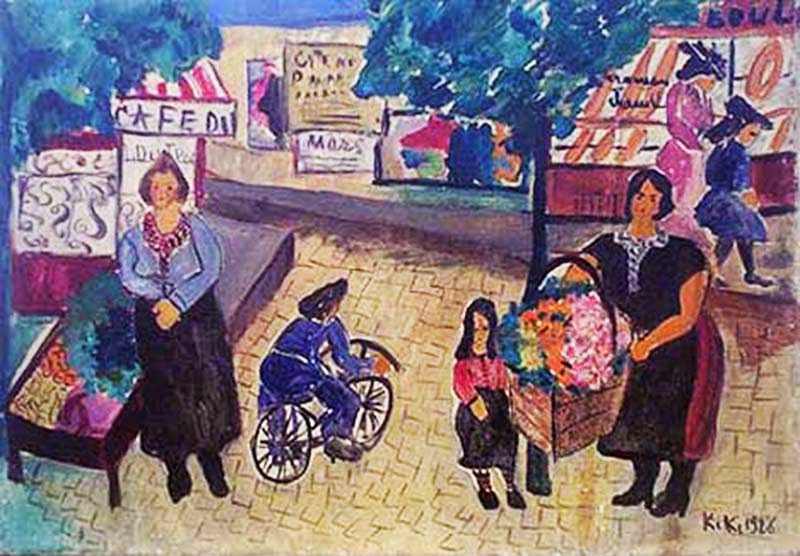

Adopting the single name “Kiki”, she became a fixture in the Montparnasse social scene and a popular artist’s model, posing for dozens of artists in the 1920’s. Soon she was simply “Kiki de Montparnasse”.

|

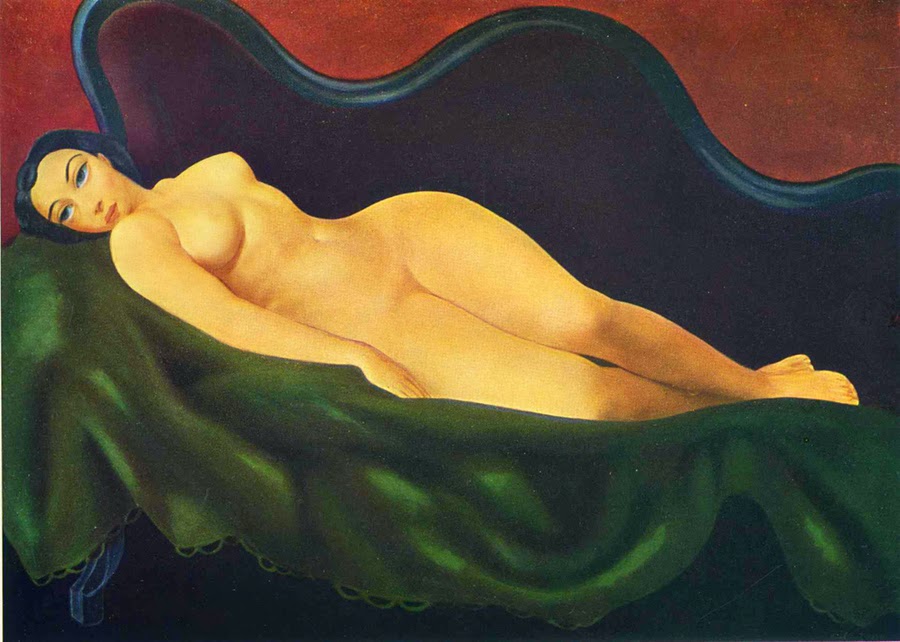

| “Reclining Nude” (Kiki) – Tsuguharu Foujita, |

|

| “Kiki de Montparnasse“, Pablo Gargallo |

Kiki became the muse of Man Ray, Kisling, Foujita, Calder, and most of the other important artists living in Paris in the 1920’s. Although all of the revolutionary writers, artists, and personalities that flourished on the Left Bank was inventing their own iconic style, Kiki was the thread connecting them. Besides modeling, Kiki was also a cabaret performer, actress, and sometimes painter.

At the end of 1920s Kiki had her own cabaret, Chez Kiki, and a table

at Le Dome was permanently reserved for her. In 1929 she published her first memoir; in 1930 the book was translated by Samuel Putnam and published in

Manhattan by Black Manikin Press, but it was immediately banned by the

United States government.

But

much like many of todays celebrities, Kiki was most famous simply for

being famous. Gossip swilled around her and Kiki revelled in it, even

when the stories were apocryphal. There was the story that she had no

pubic hair, for instance; some women, however bohemian, might have found

such speculation upsetting. Kiki didn’t.

When Man Ray’s friend and Dadaist Marcel Duchamp left for

New York, Man Ray set up his first studio at l’Hôtel des Ecoles at no.

15 rue Delambre. This is where his career as a photographer began, and

where James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau and the others often posed (see Masters of Monochrome: Part II- Man Ray ).

Kiki and Man Ray were lovers for six years, during which time he took

hundreds of photographs of her and was hugely influential in the

creation of her persona. Kay Boyle, a Paris-based American novelist and

contemporary of Kiki’s, wrote that, “Man Ray had designed Kiki’s face

for her and painted it on with his own hand. He would begin by

shaving her eyebrows off, and then putting other eyebrows back, in

any color he might have selected for her mask that day … Her heavy

eyelids might be done in copper one day and in royal blue another, or

else in silver or jade.”

But despite their intense connection, Kiki ultimately went too far for Man Ray. When a cafe-owner in Nice called her a whore she got into a fight and was thrown into jail: Man Ray’s lawyer could only secure her release by producing a doctor’s certificate stating that she had a nervous disorder. Soon afterwards, Man Ray left Kiki for his photographic protege, Lee Miller. He broke the news to Kiki at one of their regular cafe haunts, and was forced to duck under a table while she hurled plates at his head.

In 1927 Kiki had a sold-out exhibition of her paintings at the Galerie au Sacre du Printemps in Paris. Her work was composed in an uneven expressionist style that some consider a reflection of her “easy-going manner and boundless optimism”. But generally speaking, Kiki was never considered to be a serious artist; her paintings were mostly crude and amateurish. Their popularity was based not on technique or composition, but rather the name affixed to them.

Her reign ended along with the decade. She seemed unable to function outside Paris – an attempt to break into the American film industry of the 1930s failed – but Paris was no longer hers. In her last years, Kiki slipped into self-parody, singing for tourists in the Montparnasse cafes to fund her voracious cocaine and alcohol habits. In 1953, at the age of 52, she collapsed and died. Her funeral was paid for by the cafe-owners of the 6th arrondissement.

|

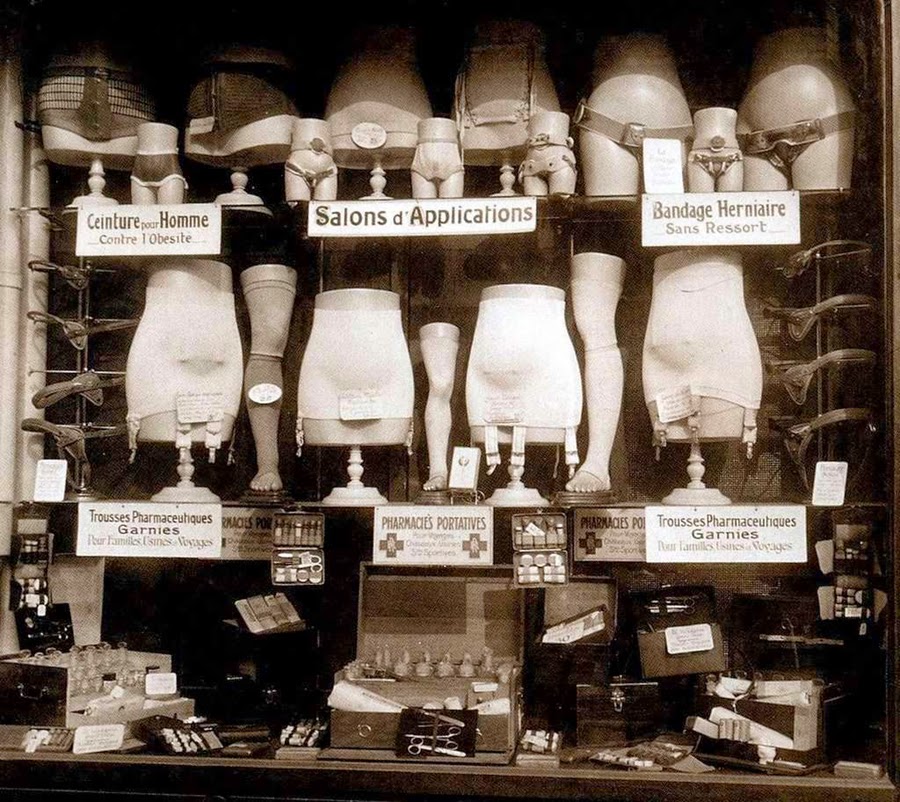

| “Café, Avenue de la Grande-Armée“, Eugène Atget 1924-25 |

|

| “La Conciergerie et la Seine“, Eugène Atget 1923 |

|

| “Boulevard de Strasbourg“, Eugène Atget 1921 |

The French photographer Eugène Atget had begun his career in the late 1880’s, but beginning with the renovations in Montmartre in 1897 his interest shifted from landscapes and portraiture to a determination for documenting all of the architecture and street scenes of Paris before their disappearance. An inspiration for the surrealists

and other artists, his genius was only recognized by a handful of contemporaries in the last two years of his life.

The Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris began purchasing his photographs in 1898, and by 1906 had commissioned him to

systematically photograph old buildings in Paris. In 1899 he moved to Montparnasse where he lived until his death in 1927. Man Ray -a neighbor of Atget – not only purchased a number of Atget’s photographs but used During the Eclipse for the cover of his surrealist magazine la Révolution surréaliste.

When he asked Atget if he could use his photo Atget said: “Don’t put my

name on it. These are simply documents I make.” Despite being documentary in intent, Atget’s pictures of staircases, doorways, ragpickers, and especially

those with window reflections and mannequins had a Dada or Surrealist

quality about them. Man Ray offered to lend him his modern compact cameras but Atget refused, preferring to use the older equipment which he hauled around the streets.

|

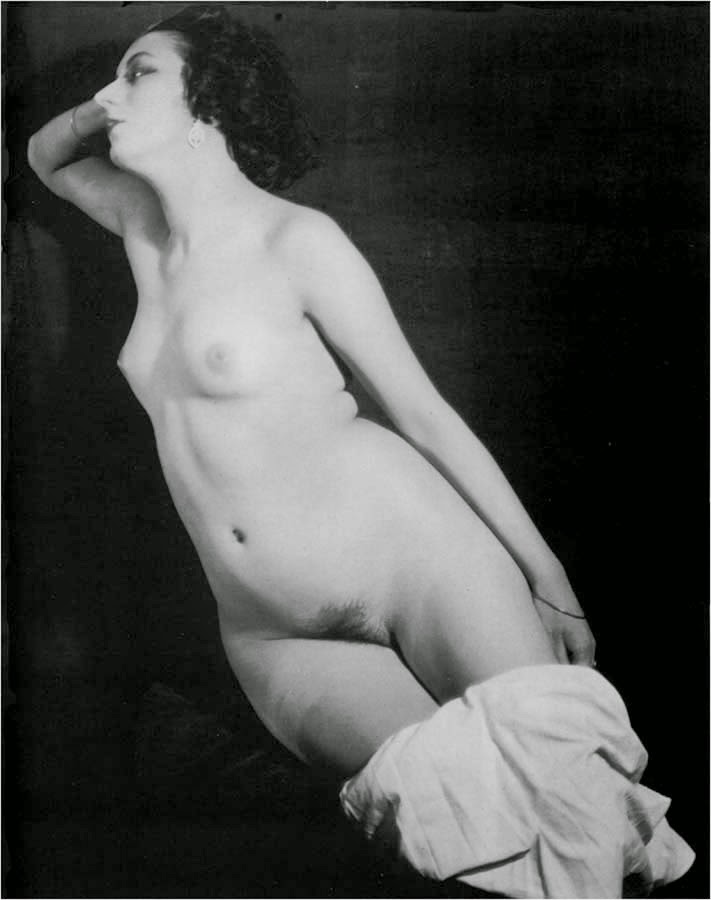

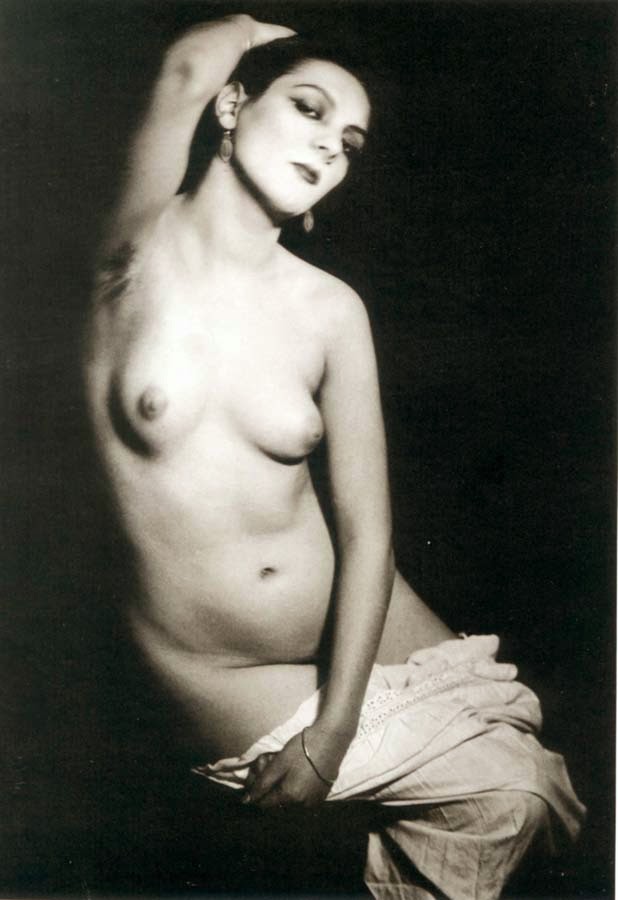

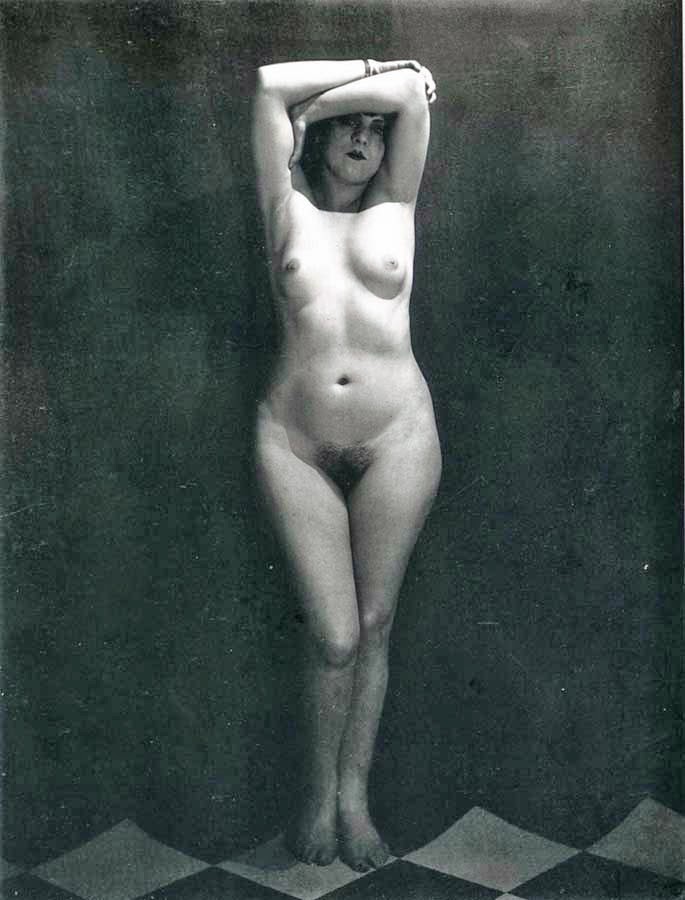

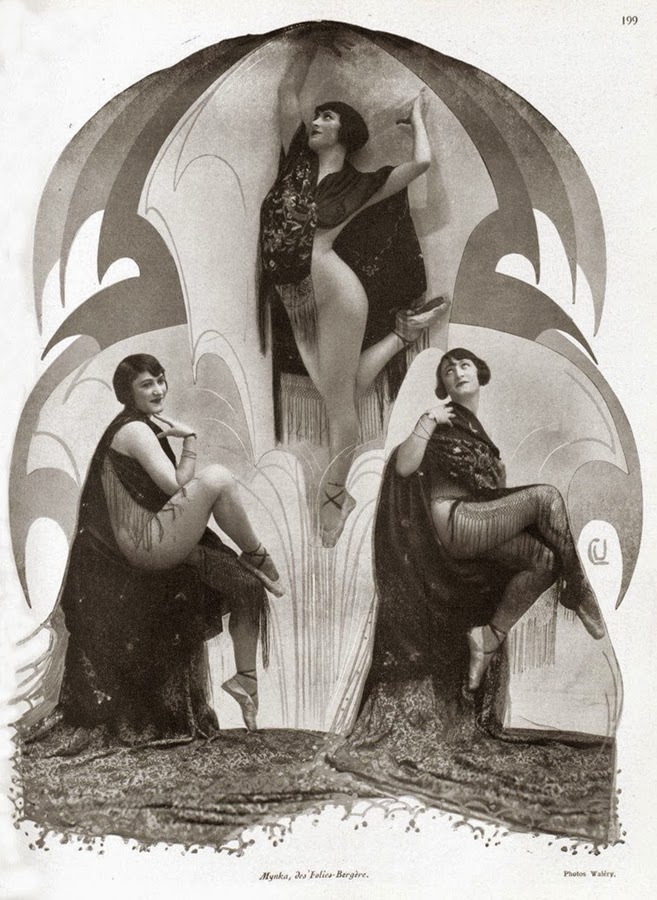

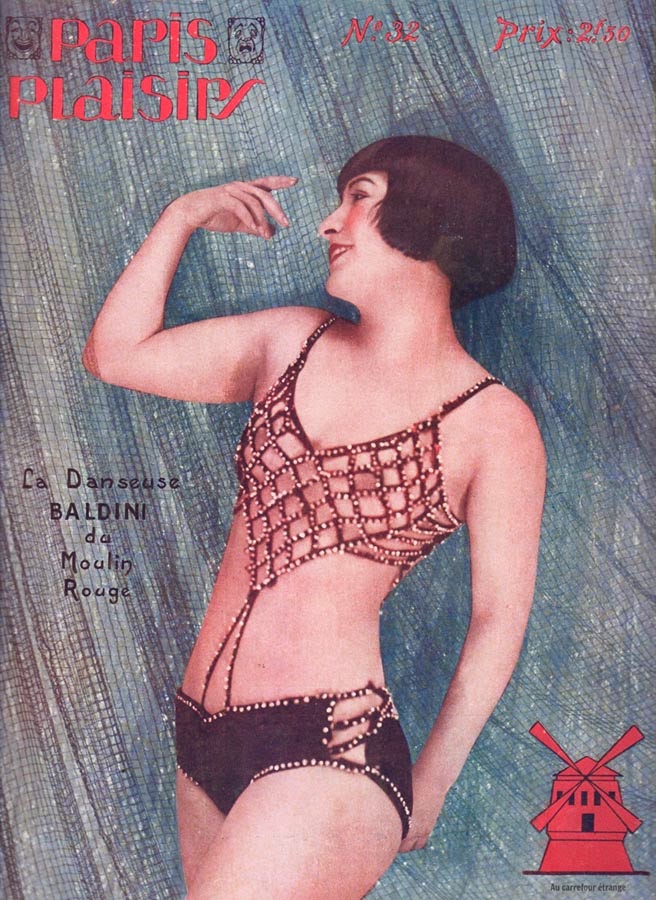

| Advertisement for Moulin Rouge, Lucien Walery |

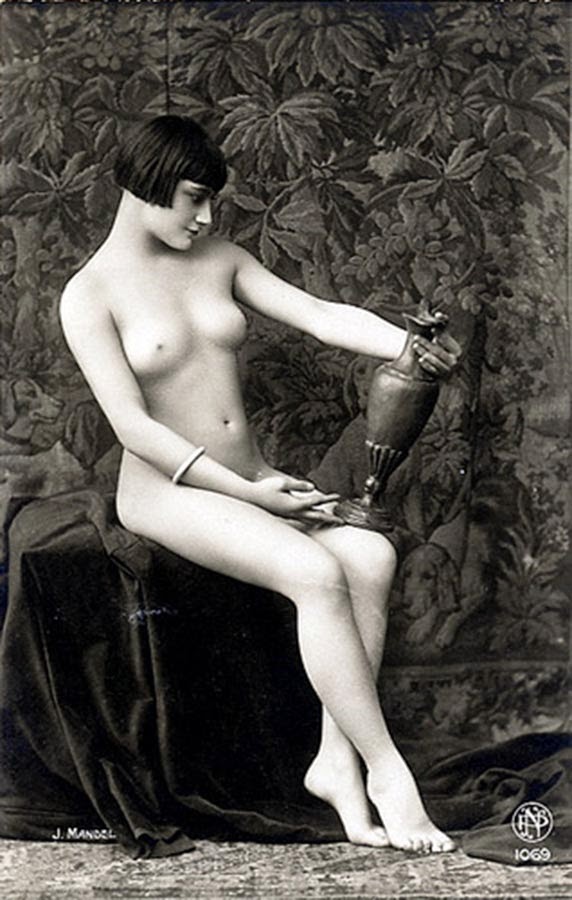

The mysterious but prolific Lucien “Julien” Waléry was another renowned Parisian photographer during the 1910’s and twenties; he became famous for his portraits of artists and cabaret-dancers from the Paris music halls, especially the Folies Bergère and demi-monde society. Among his best known portraits are Mata Hari and Josephine Baker. His photos were often signed “Walery, Paris”. It is said that he also used the anagrams “Yrélaw” or “Laryew”.

There has been some controversy involved over a studio photographer of the period which specialized in erotic “postcards”, known as “Julian Mandel”. Signature photography bearing that name was published in Paris throughout the same time frame by firms specializing on risque imagery such as Alfred Noyer, Les Studios, P.C. Paris and the Neue Photographische Gesellschaft, a few of them featuring a young Kiki. Waléry did a lot of erotic nude photographs, and it may well be that he used the name “Mandel” when selling work to publishers: the use of the name “Julian” and the similarity of the imagery is too great to write off as mere coincidence. Another controversy revolves over the possibility that Waléry’s actual identity was Stanislaw Julian Ignacy Count Ostroróg (1863-1935), a British photographer from London with Polish ancestors, providing a possible explanation for his subterfuge.

|

| Carrefour Vavin |

“The cafe is not only a place to enjoy a cup of coffee, it is also a space – distinct from its urban environment – in which to reflect and take part in intellectual debate. Since the eighteenth century in Europe, intellectuals and artists have gathered in cafes to exchange ideas, inspirations and information that has driven the cultural agenda for Europe and the world. Without the café, would there have been a Karl Marx or a Jean-Paul Sartre?” – Leona Rittner, The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna

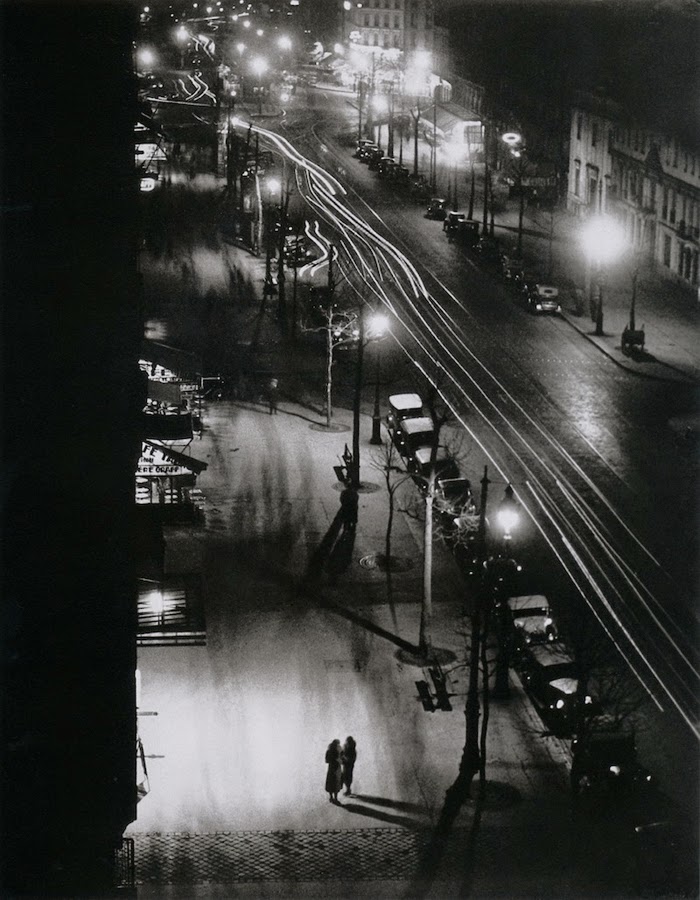

The cafés at the centre of Montparnasse’s social life were in the

Carrefour Vavin, now known as Place Pablo-Picasso. During les Années Folles, Le Dôme, La Closerie des Lilas, La

Rotonde, Le Select and La Coupole (all still in operation)

were popular among the artists and writers who could occupy a table all evening

for a few centimes. If they fell asleep waiters were usually instructed not

to wake them. Arguments were common, fueled by intellect and alcohol; fights often erupted but the police

were summoned only as a last resort. It was common for artists to run tabs at their favorite cafes, often paying with paintings or other works; some of them were virtually galleries by their own right.

Near Le Dôme at no. 10 rue Delambre was the Dingo Bar, a hang-out for expatriate Americans and frequented by

Canadian writer Morley Callaghan, Hemingway and F. Scott

Fitzgerald.

|

| Dingo American Bar, 10 rue Delambre |

|

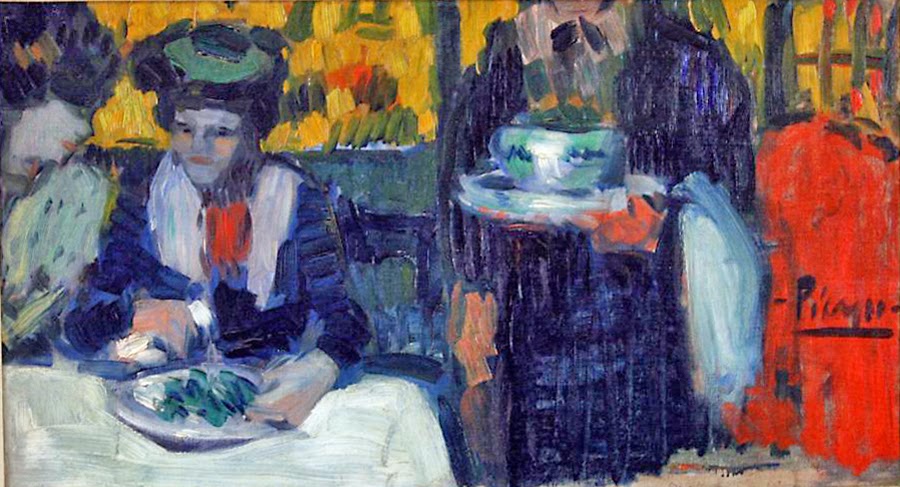

| “La Rotonde“, Pablo Picasso |

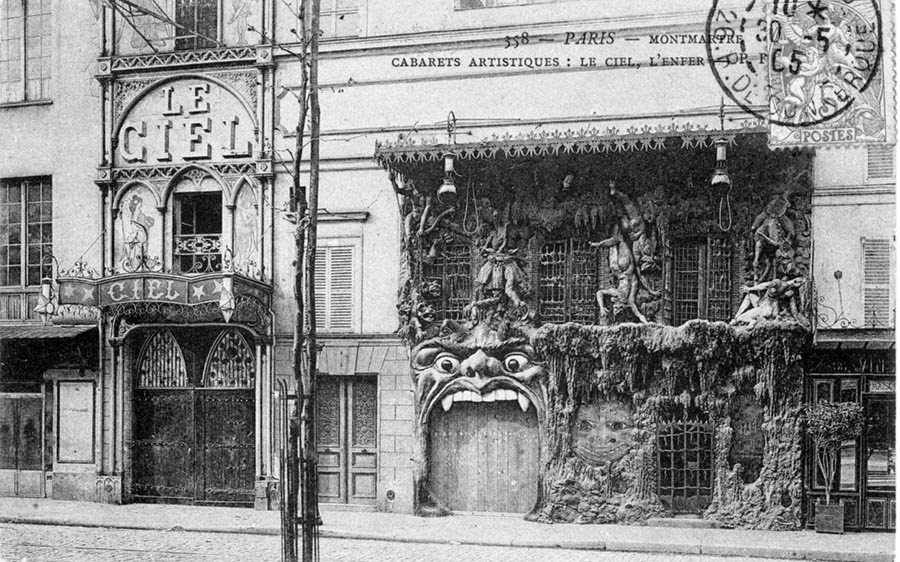

Bohemians of the Latin Quarter had inspired the first modern cabaret in Paris that emerged in Montmartre. Rodolphe Salis, an entrepreneurial entertainment agent, created the Chat Noir in 1881; the Moulin Rouge followed in 1889.

Le Chat Noir’s original attraction was not half dressed women and sultry singers, rather it was intended as a kind of salon where Parisian artists and intellectuals like Maupassant, Debussy, and Satie could gather to share ideas and compositions. The arrangement benefited everyone involved; artists would get an opportunity to test new material and, for the price of a few drinks, audience members would get to experience a stimulating evening of theatre. By 1900 the idea had spread, and numerous cabarets had opened in France and Germany. At this point, however, the cabaret evolved into something strikingly different from the free form artist’s haven of Le Chat Noir.

The rue de la Gaité in Montparnasse was

the site of many of the local cabarets, in particular the

famous “Bobino“. On their stages, using then-popular single name

pseudonyms or one birth name only, Damia, Kiki, Mayol and Georgius sang

and performed to packed houses. Even Picasso branched

out into the world of music and the theatre with Jean Cocteau’s staging of

‘Parade.”

|

| Le Café de L’Enfer a Hell-themed café/cabaret in the Pigalle red light district. |

Cabaret became a style of performance characterized by an intimate nightclub setting featuring a variety of entertainers and an ever present emcee. By its nature, cabaret is a personal experience between audience and performer; the close proximity of the performer to the audience allowed for a deeper and more intense relationship. The performer could see and hear every sound in the audience while the audience could see every bead of sweat and every trick up the performer’s sleeve. The immediacy of the event thus required the cabaret performer to be spontaneous, honest, and, above all, versatile.

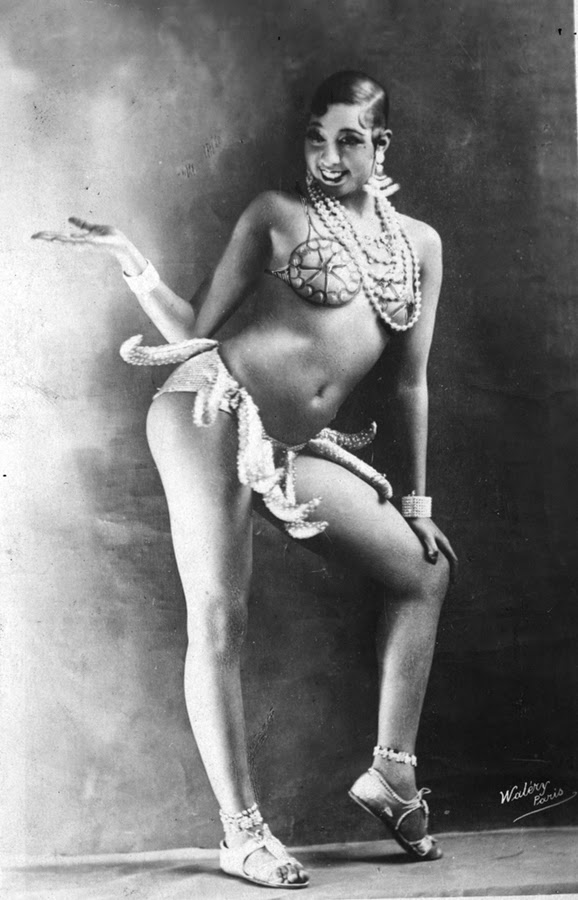

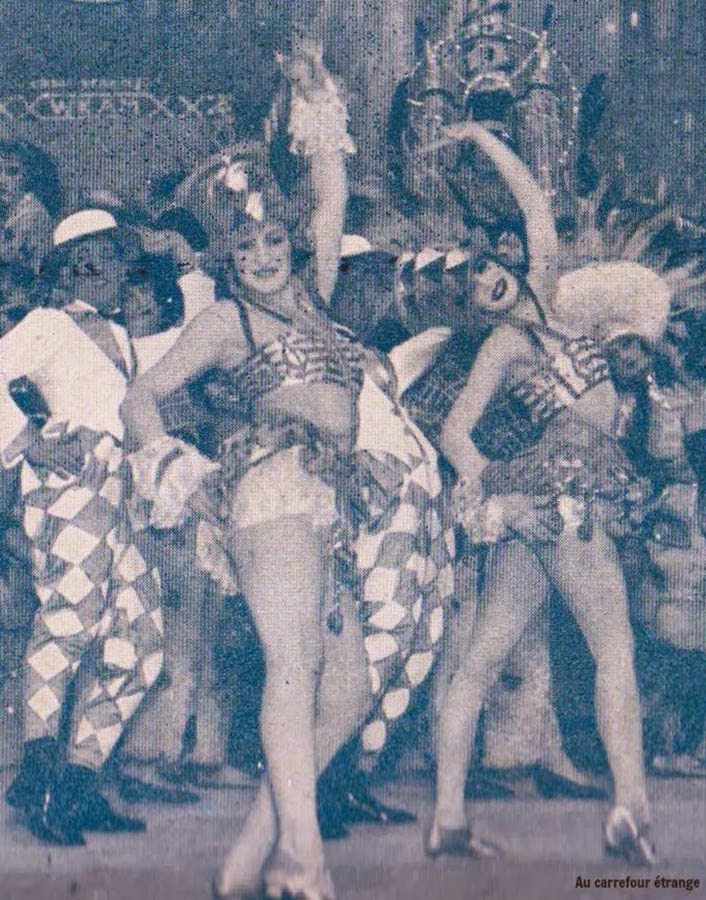

While the French had great composers and performers, many were Americans who came to Paris before the local Parisians jumped on the bandwagon. George Antheil lived in Paris and performed his Symphony Mechanic; Aaron Copeland studied under Nadia Boulanger and wrote his Organ Symphony in 1924. Everyone knew of Gershwin, Cole Porter and Maurice Ravel. But it was French entertainers like Ada “Bricktop” Smith and the American born Josephine Baker who performed nightly to enthusiastic Paris audiences.

Josephine Baker was a household name; born in 1906 in St. Louis, Missouri, her parents had a song-and-dance act, playing wherever they could get work, and when Josephine was about a year old they began to carry her onstage occasionally during their finale. Josephine was always poorly dressed and hungry, and her playground became the yards of Union Station. Like Kiki, she soon developed “street smarts”.

Baker dropped out of school at the age of 13 and lived as a street child in the slums of St. Louis, sleeping in cardboard shelters; her street-corner dancing attracted attention and she was recruited for the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show two years later. She soon headed to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance, performing at the Plantation Club and in the chorus of several hugely successful Broadway revues. Baker traveled to Paris for a new venture, and opened in “La Revue Nègre” on October 2, 1925 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

In Paris she became an instant success for her erotic dancing and appearing practically nude on stage. After a successful tour of Europe she broke her contract and returned to France to star at the Folies Bergère, setting the standard for her future acts. She performed her signature Danse sauvage wearing a costume consisting of nothing more than a skirt made from a string of artificial bananas.

But despite her popularity in France, Baker never obtained the same reputation in America. Upon a visit to the United States in 1935–36, American audiences rejected the idea that a black woman could be so sophisticated; her star turn in the Ziegfeld Follies generated less than impressive box office numbers, and she was replaced by Gypsy Rose Lee later in the run. Time magazine referred to her as a “Negro wench”.

She returned to Europe heartbroken, but was soon the most successful American entertainer working in France. Ernest Hemingway called her “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw.”

|

| From Left: Myrsine and Helene Moschos (clerks), Sylvia Beach, Ernest Hemingway in front of Shakespeare and Company. |

“We all went to Paris. It was where we had to be.” – Gertrude Stein

|

| Gertrude Stein & Alice Toklas |

After the war many previously healthy and hopeful American young men

returned home emotionally or physically broken, with little faith in

their government or hope for the future. WWI brought change to all of America but most notably it brought Prohibition. In Paris rents were low,

drinking was allowed, women were considered relatively emancipated, and the

art scene was welcoming. As Fitzgerald put it, “Here was a new generation, grown up to find all

wars fought, all Gods dead and all faith in mankind shaken.” They were looking for change and freedom. They found it in Paris.

Between 1921 and 1924 the number of Americans in Paris swelled from

6,000 to 30,000. While most of the artistic community gathered there were

struggling to eke out an existence, well-heeled American socialites

such as Peggy Guggenheim and Edith Wharton from New York City, Harry

Crosby from Boston and Beatrice Wood from San Francisco were also caught up in

the fever of creativity.

Robert McAlmon, and Maria and Eugene Jolas came

to Paris and published their literary magazine, Transition. Harry Crosby

and his wife Caresse would establish the Black Sun Press in

Paris in

1927, publishing works by such future luminaries as D. H. Lawrence,

Archibald MacLeish, James Joyce, Kay Boyle, Hart Crane, Ernest

Hemingway, John Dos Passos, William Faulkner and Dorothy Parker. Bill

Bird also published through his Three Mountains Press until

British heiress Nancy Cunard took it over.

|

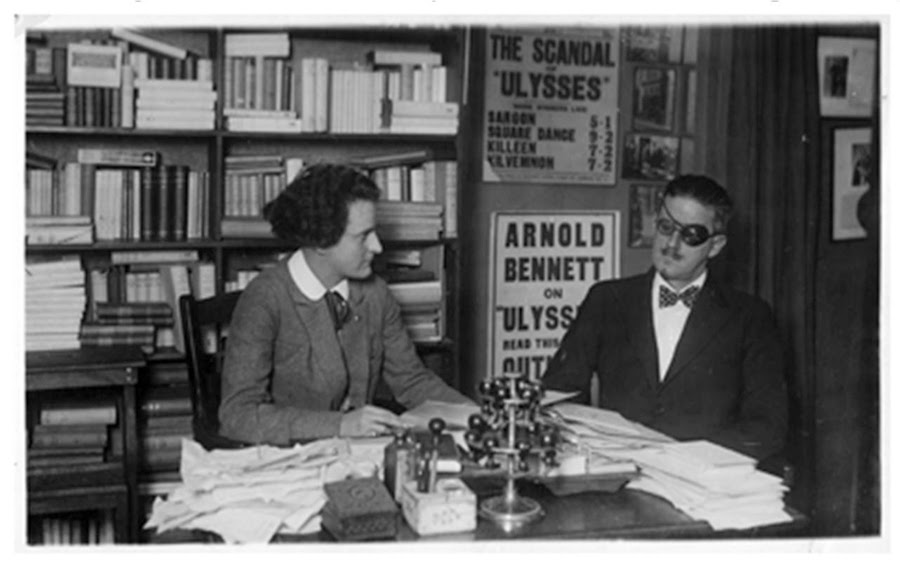

| Sylvia Beach with James Joyce |

|

| Beach and Monnier |

One of the most influential literary institutions of the era was Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company. Beach’s lifelong companion, Adrienne Monnier, owned the bookstore La

Maison des Amis des Livres and had encouraged Beach to open her own store in 1919. After a brief stay on the rue Dupuytren, she moved to a location

across from the shop of Monnier on the rue de l’Odéon. Along with the publishers and periodicals, the English-language bookstores

were an invaluable support to the expatriate community; a combined bookstore

and lending library, Shakespeare and Company quickly became a center

of activity in the growing expatriate community.

Shakespeare & Co. served as the sales address and principal

Paris distribution point for many of the local English-language publishers

and periodicals. Beach befriended, advised, and lent books to countless

expatriate writers, among them Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, and Robert

McAlmon, many of whom used the shop as their mailing address.

Beach’s most

famous association was with James Joyce and her subsequent publication of his novel

Ulysses using the printing

services of Maurice Darantière in Dijon. Beach published the first

edition under the imprint of Shakespeare and Company in 1922.

Sylvia Beach attempted to stay on after the German occupation of

Paris but finally closed her shop in late 1941 after a Nazi officer threatened

to confiscate her books. She declined to reopen after the war

but continued to lend books from her apartment to a new generation

of expatriate writers, among them the American Richard Wright.

On the face of it the sobriquet of “génération perdue” -the” Lost Generation”- seems an odd collective description for a group of writers and artists who were among the brightest American literary talent ever to emerge on the international stage. While Gertrude Stein- the scene’s abiding spirit and prominent literary hostess- had coined the phrase, it was undoubtedly Hemingway’s use of it as the epigraph to The Sun Also Rises that made clear its apocalyptic overtones. Both the phrase and the book depicted this generation as characterized by doomed youth, hedonism, uncompromising creativity; wounded, both literally and metaphorically, by the experience of war. To varying degrees these virtues and vices were to be found in the life story of nearly every member of the Lost Generation. Yet aside from their wild lifestyles the most striking feature of that literary era is the astonishing range, depth, and influence of work produced by the community of American expatriates in Paris.

|

| Fascist Riots, Paris 1934 |

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 sent a shiver through the American expatriates, but the French considered their economy sufficiently isolated thanks to gold reserves. They were wrong. The Great Depression reached France around 1931, and les Années Folles slowly ground to a halt.

The French government was

made up of numerous political parties which were unable to cooperate with each

other for very long. In 1933, five coalition cabinets formed and quickly fell.

As a result, the unity which had made government instability bearable collapsed; fascist groups arose using Nazi Germany and Benito Mussolini for inspiration. In February, 1934, French fascists rioted and

threatened to undermine the republic.

Communists demanded that

France support the Spanish Republicans while the conservatives would have been

happy to join Mussolini and Hitler in aiding the Spanish fascists. France was on

the brink of civil war when Blum was forced to resign in June 1937 and the

Popular Front quickly collapsed. From there, France drifted aimlessly, preoccupied with

Hitler and the rearmament of Germany.

References:

Artistic Community and Urban Development in 1920s Montmartre: Jeffrey H Jackson, French Politics, Culture & Society 2006

La Ruche et ses artistes aujourd’hui: Daniel Lebée, au musée du Montparnasse (PDF)

Les Souvenirs de Kiki de Montparnasse: Alice Prin (Kiki) 1929 (PDF)

Très belle revue de la période, particulièrement intéressante pour un français par la distance avec le point de vue un peu nombriliste de mes concitoyens. L’iconographie est délicatement choisie. Un bon moment passé en s’immergeant dans une période qui s’est assez mal terminée.