Masters of Monochrome: Part VI- Bill Brandt

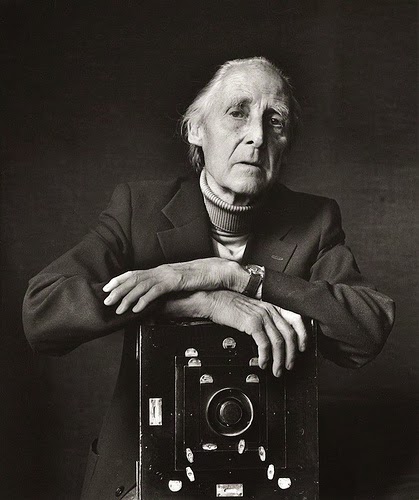

Bill Brandt was born in Hamburg on 2 May 1904 to an English father and a German mother, although after the rise of Nazism he disowned his German background and later life claimed to born in south London.

He probably took up photography while undergoing treatment for tuberculosis in Switzerland; in 1927 he traveled to Vienna where he was befriended by Dr. Eugenie Schwarzwald, who not only found him work in a local portrait studio but likely introduced him to American poet Ezra Pound. Pound in turn introduced Brandt to Man Ray, and he worked as Ray’s assistant in Paris for several months in 1930.

He also traveled in continental Europe with Eva Boros, whom he had met in the Vienna studio. They married in Barcelona in 1932.

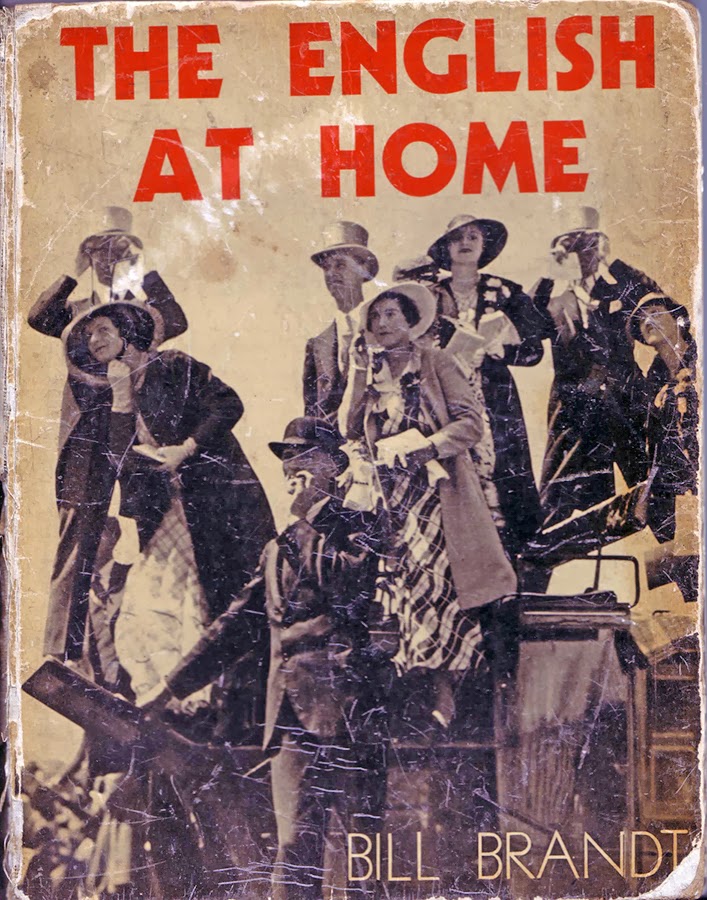

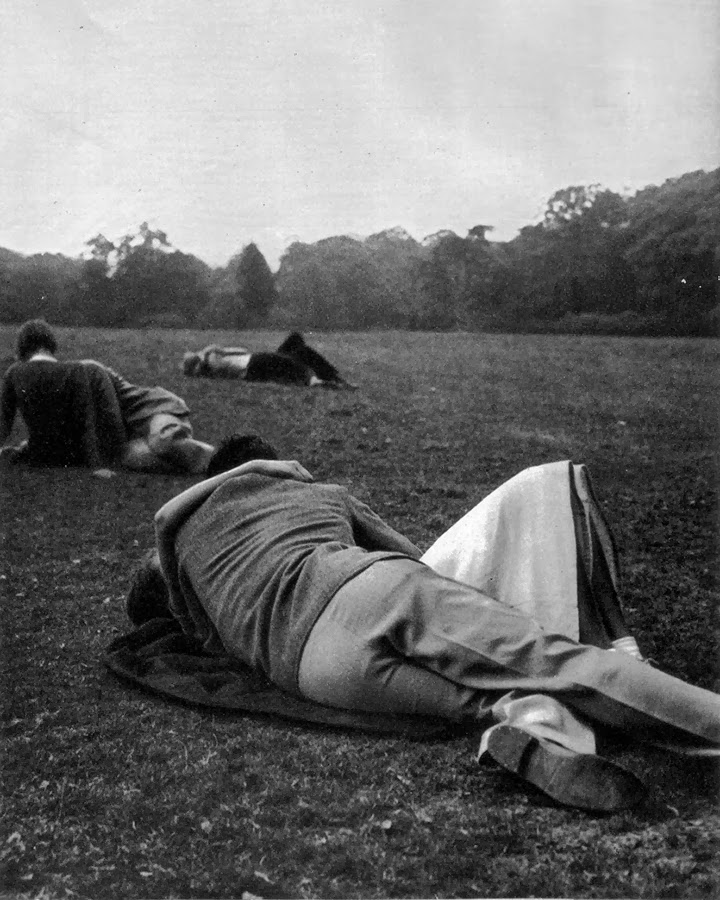

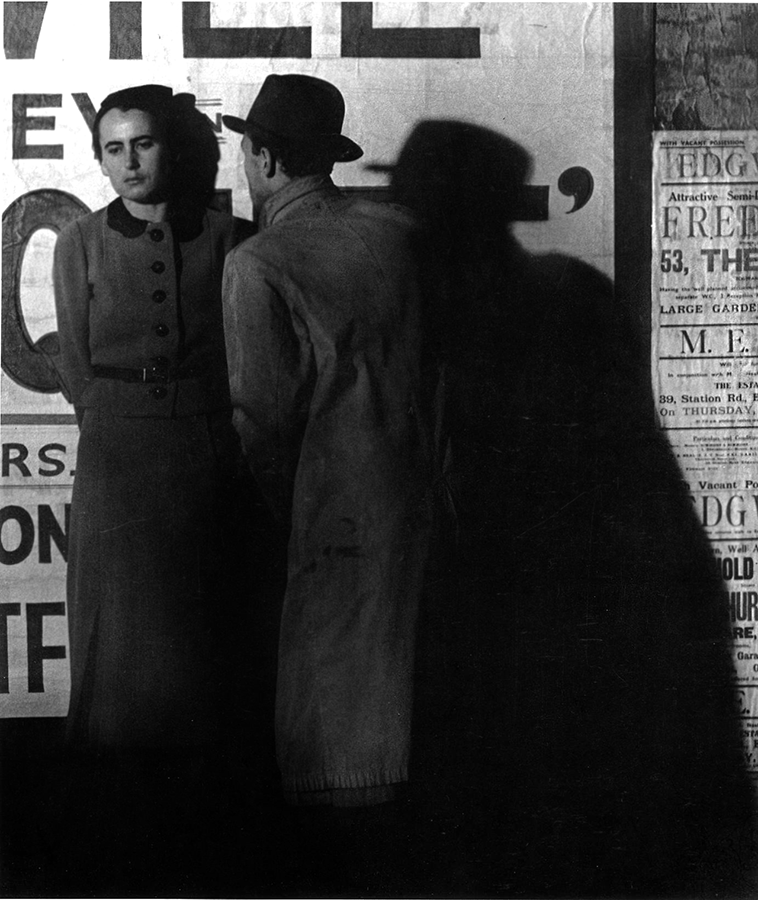

Brandt had visited England during the late 1920s and in 1934 he and his wife settled in Belsize Park, north London. He photographed on occasion for the News Chronicle and Weekly Illustrated, and finally found steady work as a photojournalist with the foundation of Lilliput and Picture Post by editor Stefan Lorant in late 1937. The majority of Brandt’s earliest English photographs were first published in Brandt’s The English at Home (1936).

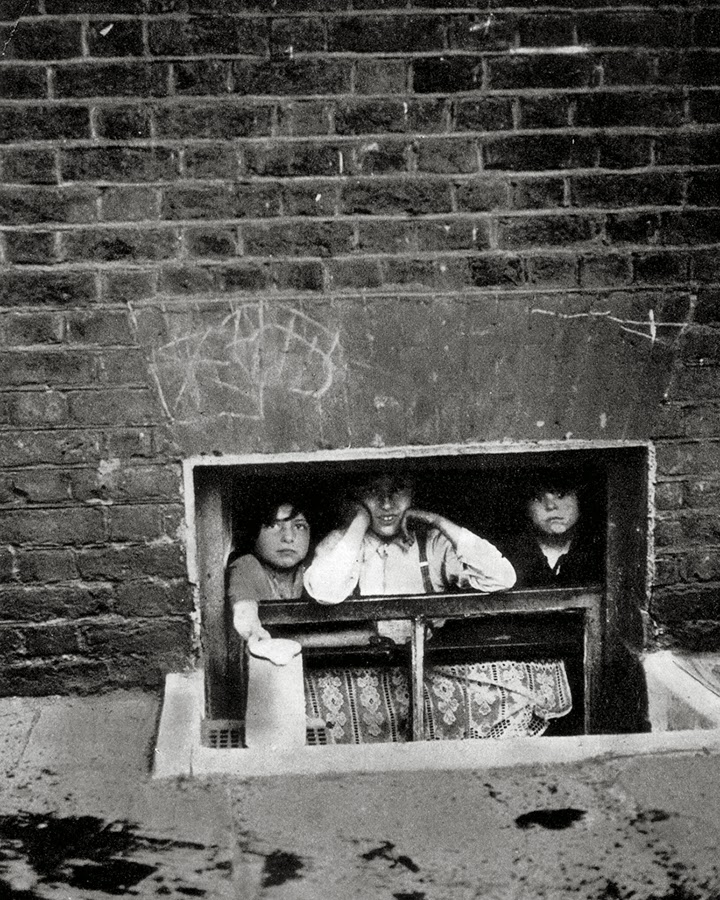

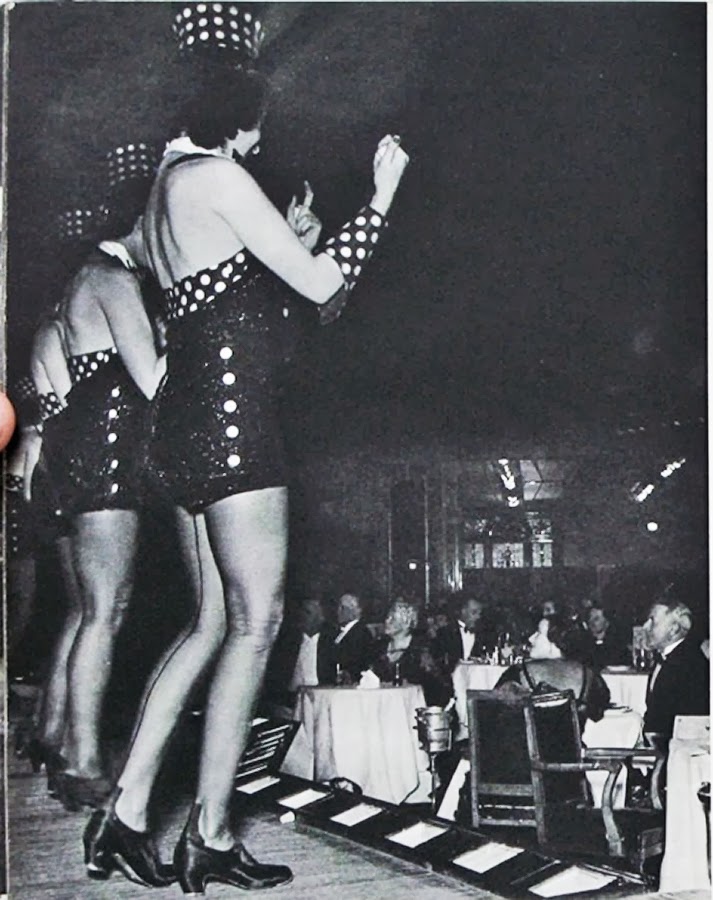

The young photographer used his family contacts – for example, his banker uncles – to gain access to a variety of subjects for The English at Home, and the book contained a number of pointed social contrasts, such as the high life presented on the front cover and a poor family shown on the back cover. Raymond Mortimer’s introduction to the book praised Brandt for the freshness of his observation and the acuteness with which he saw and photographed such contrasts.

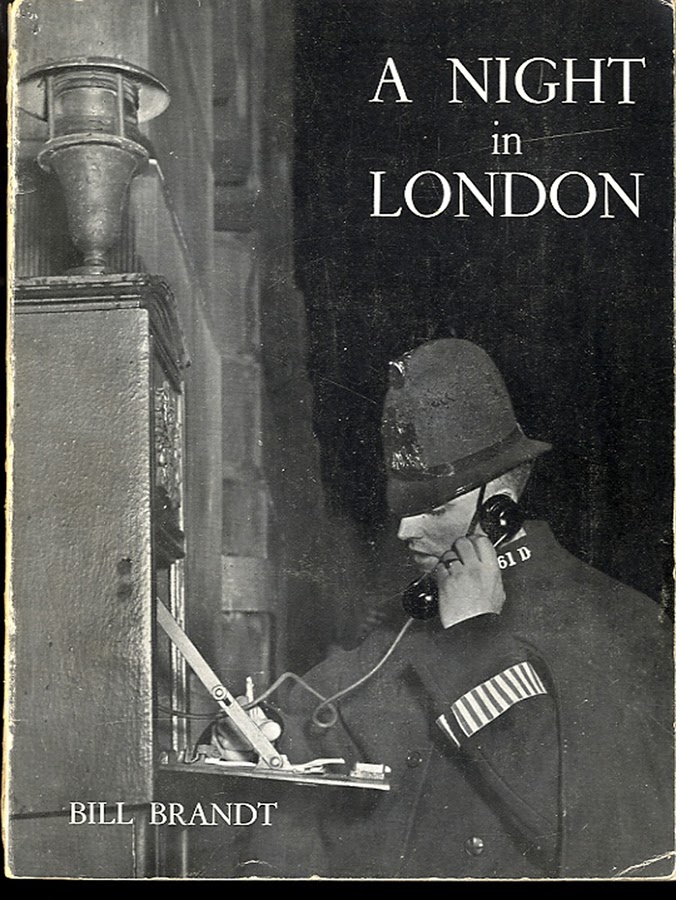

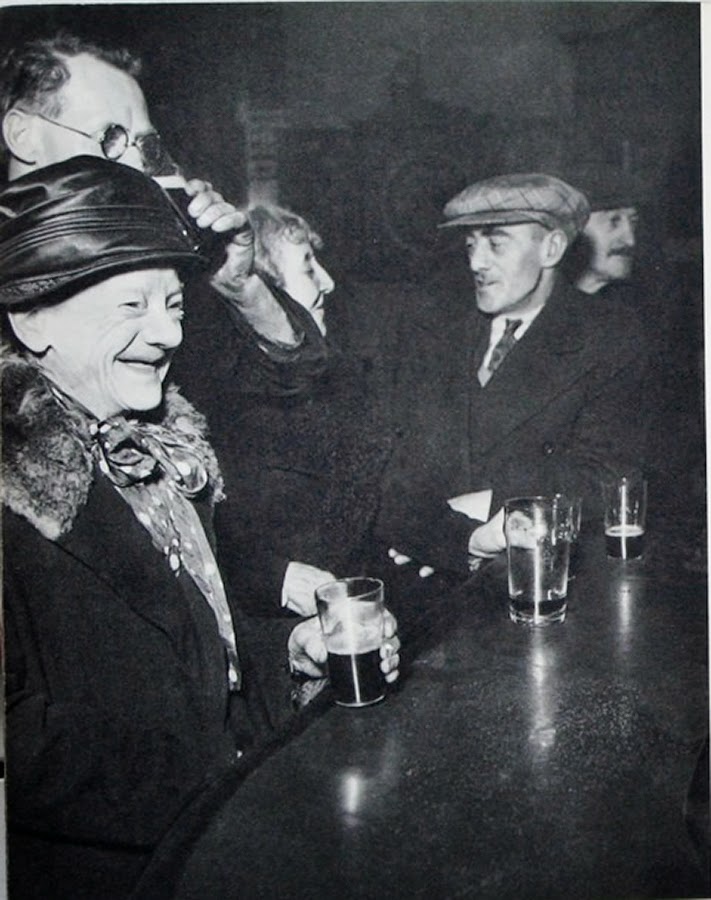

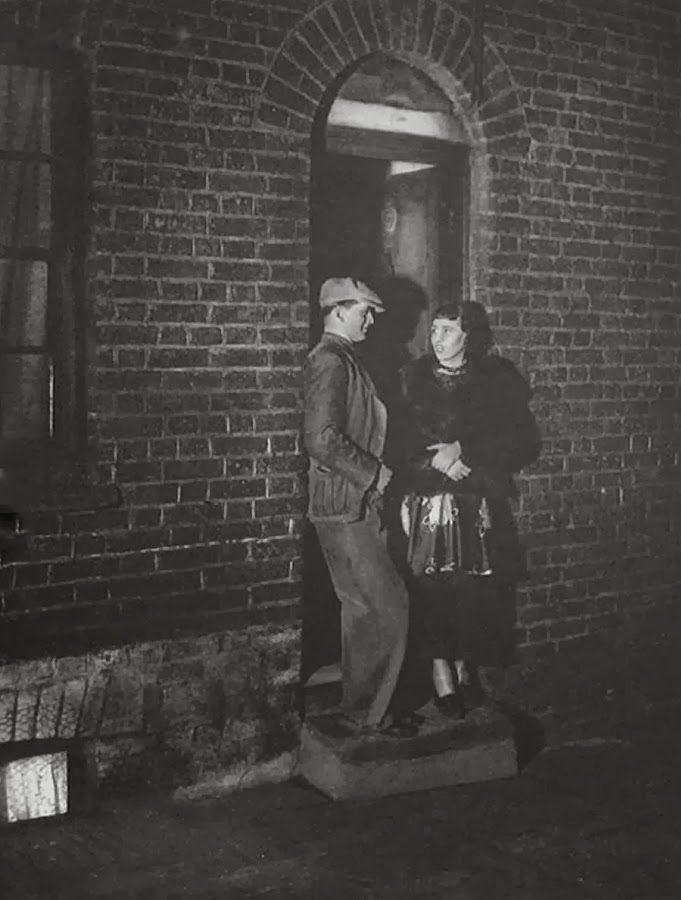

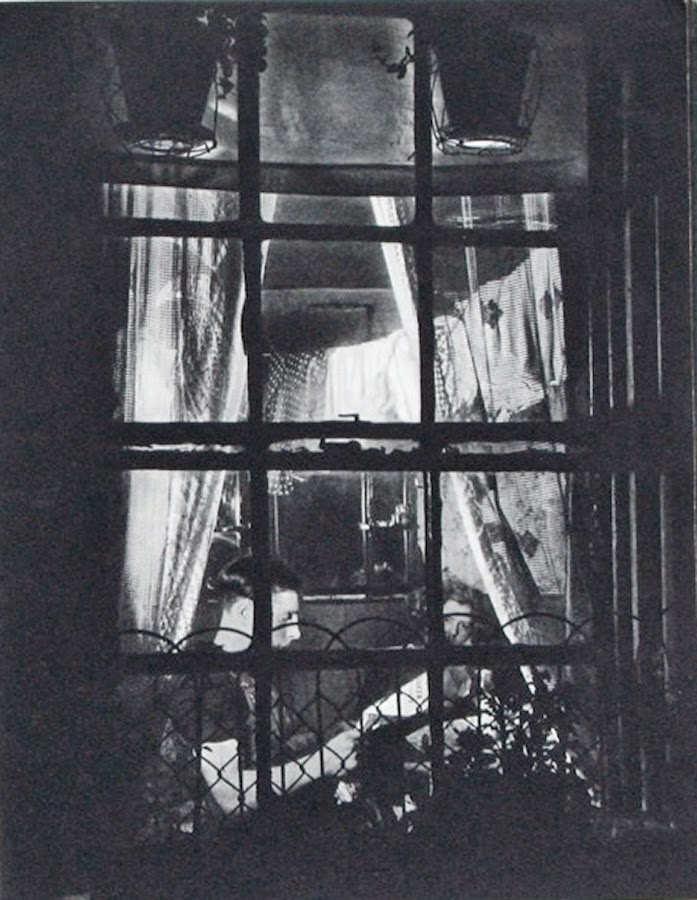

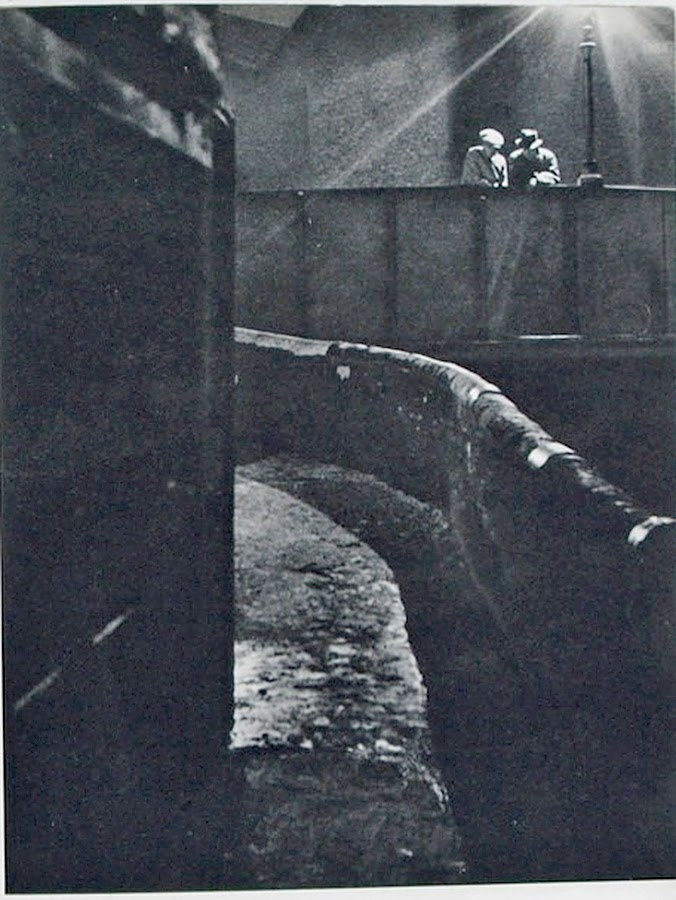

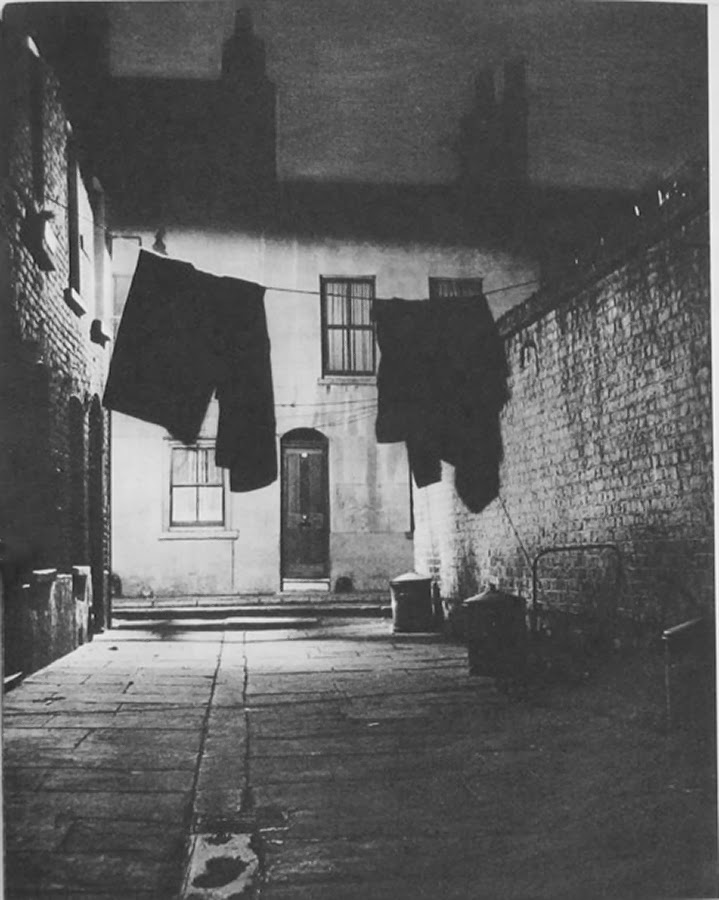

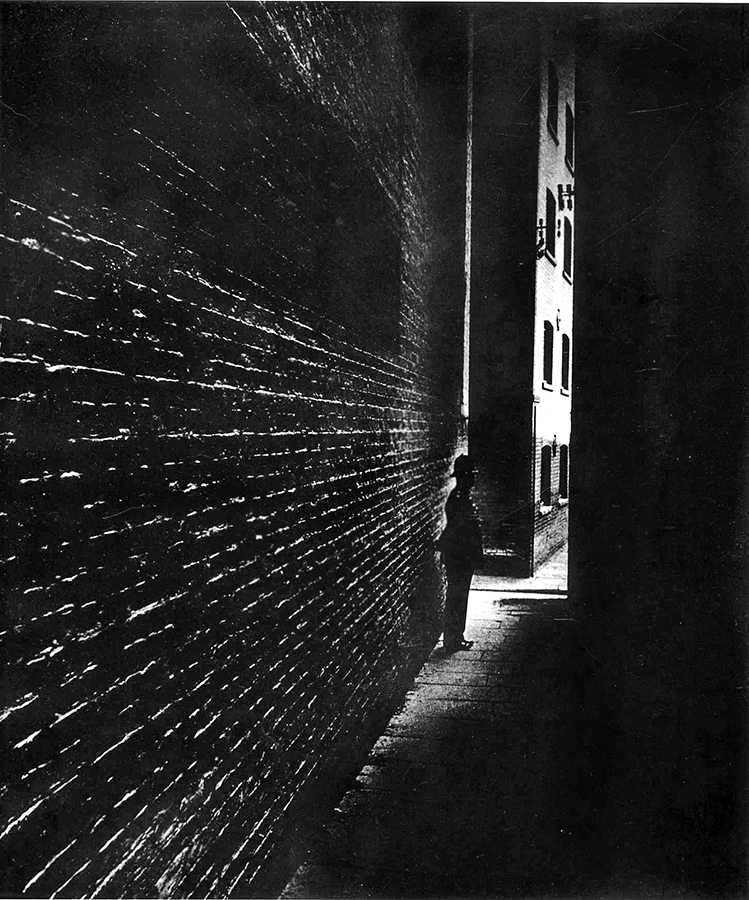

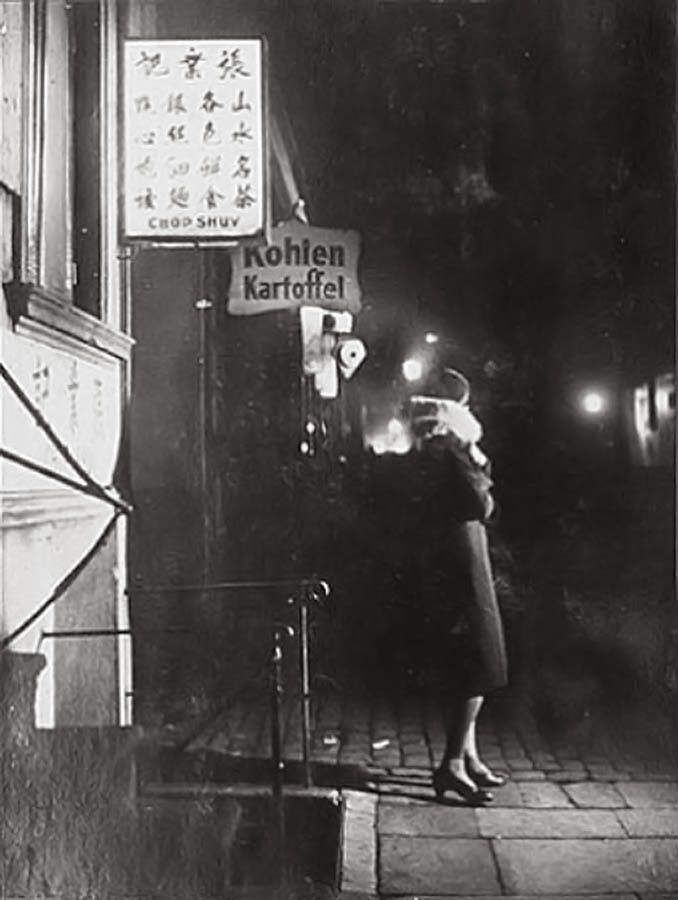

Two years later he published a second book, A Night in London, based on Brassai’s Paris de Nuit (1936) which Brandt had greatly admired. The book tells the story of a London night, again moving between different social classes. Night photography was a new genre, made possible by the newly developed flashbulb (the ‘Vacublitz’ was manufactured in Britain from 1930). Brandt generally preferred to use portable tungsten lamps called photo-floods, and claimed to have enough cable to run the length of Salisbury Cathedral.

In his introduction to Brandt’s second book James Bone described the new, electric city: “Floodlit attics and towers, oiled roadways shining like enamel under the street lights and headlights, the bright lacquer and shining metals of motorcars, illuminated signs…”

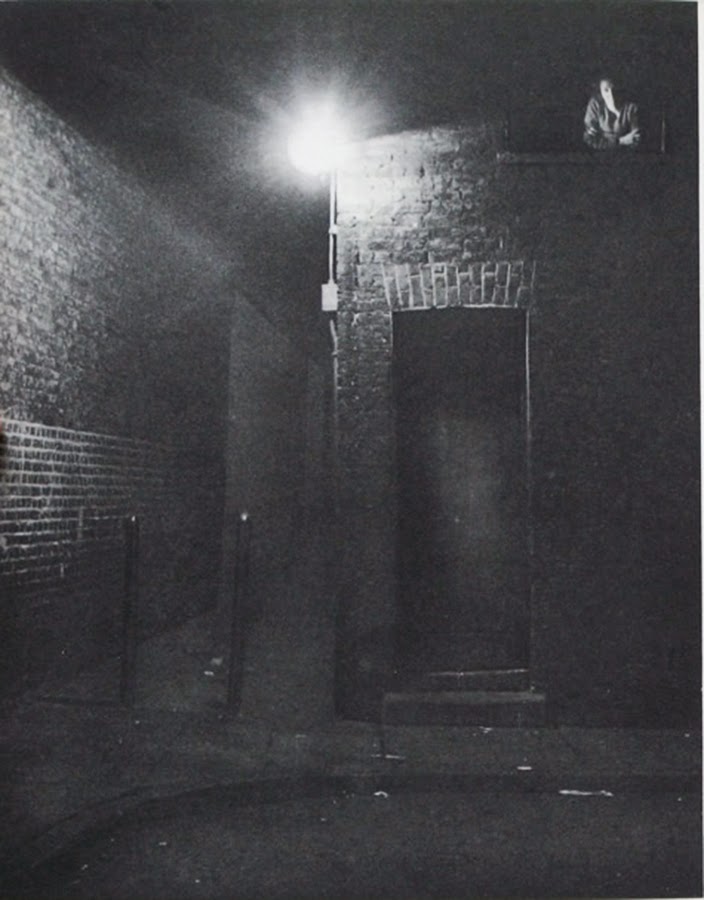

Brandt often used the darkroom to alter his photographs in decisive way. For example, in the photograph Policeman in a Dockland Alley he used the ‘day for night’ technique employed by cinematographers to transform images photographed in daylight into night scenes.

In 1936 Bill Brandt met Tom Hopkinson, then assistant editor of Weekly Illustrated and later editor at Lilliput and Picture Post. Hopkinson described Brandt as having ‘a voice as loud as a moth and the gentlest manner to be found outside a nunnery’. Brandt went on to propose pictures and stories for both magazines. He often sequenced his photo-essays, sometimes also contributing text.

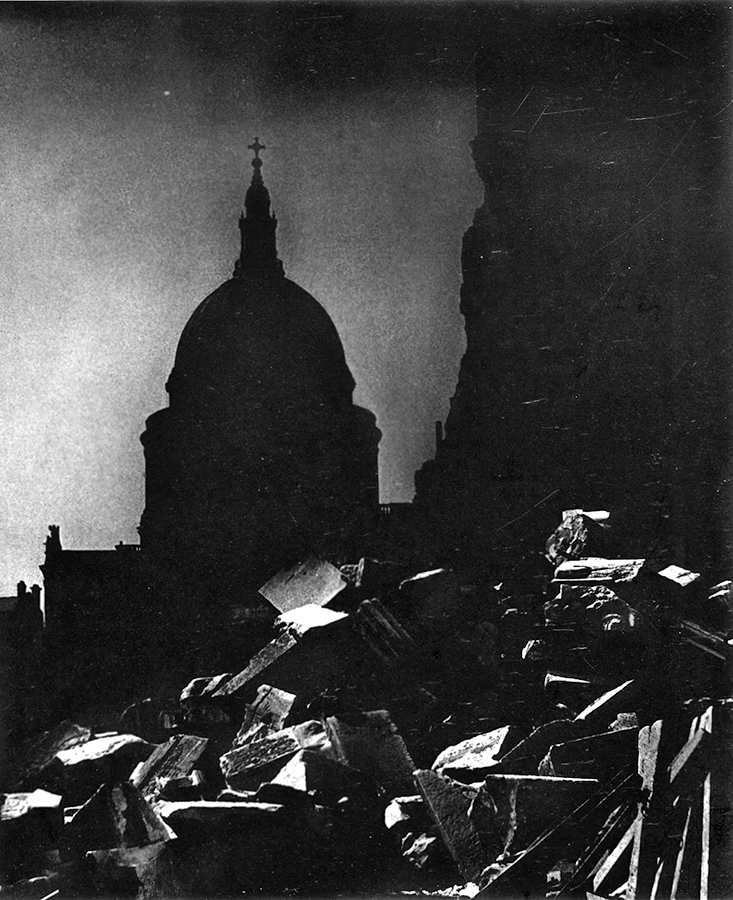

The blackout photographs, probably Brandt’s own idea, were made during the brief period after war had been declared but before serious hostilities between Britain and Germany had begun: a second set was made in 1942. After the London Blitz began, Brandt was commissioned to record bomb shelters by the Ministry of Information. His photographs were sent to Washington as part of the British government’s attempt to bring the US into the war on the allied side.

Elizabeth Bowen, one of Brandt’s favourite writers, wrote in her story ‘Mysterious Kôr‘: “Full moon drenched the city and searched it; there was not a niche left to stand in. The effect was remorseless: London looked like the moon’s capital – shallow, cratered, extinct…And the moon did more: it exonerated and beautified”.

Cyril Connolly published Brandt’s shelter photographs in Horizon in February 1942. In 1966 Connolly wrote that “Elephant and Castle 3.45 a.m. eternalises for me the dreamlike monotony of wartime London.” Brandt himself recalled “…the long alley of intermingled bodies, with the hot, smelly air and continual murmur of snores”.

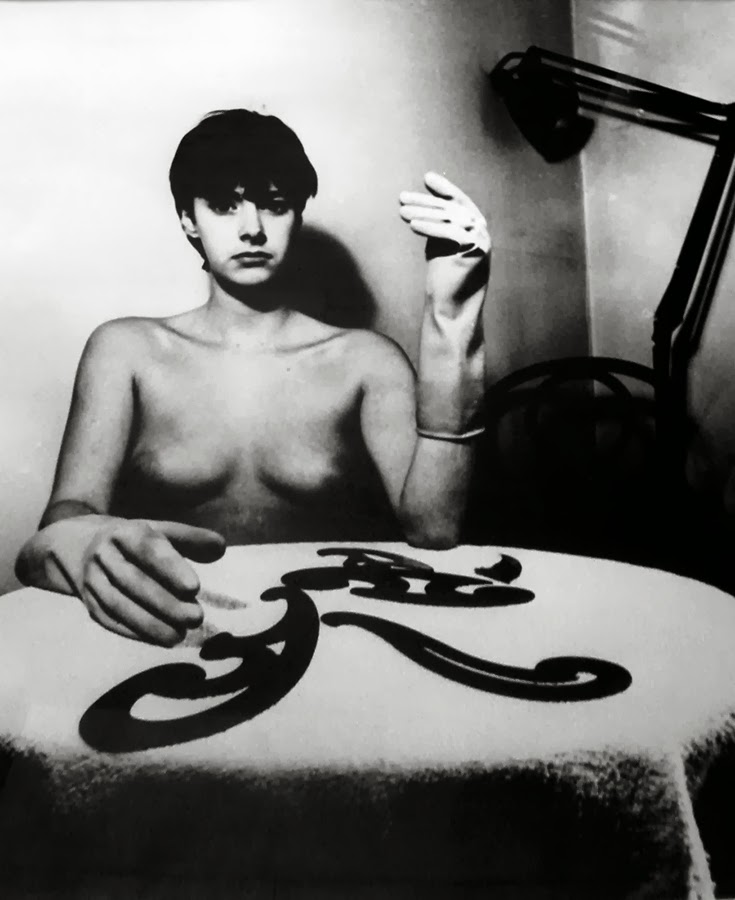

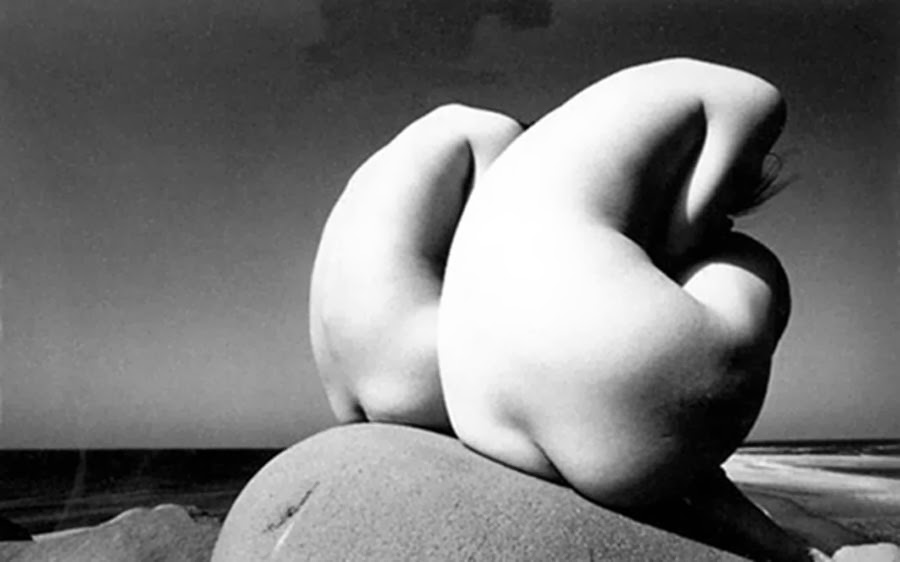

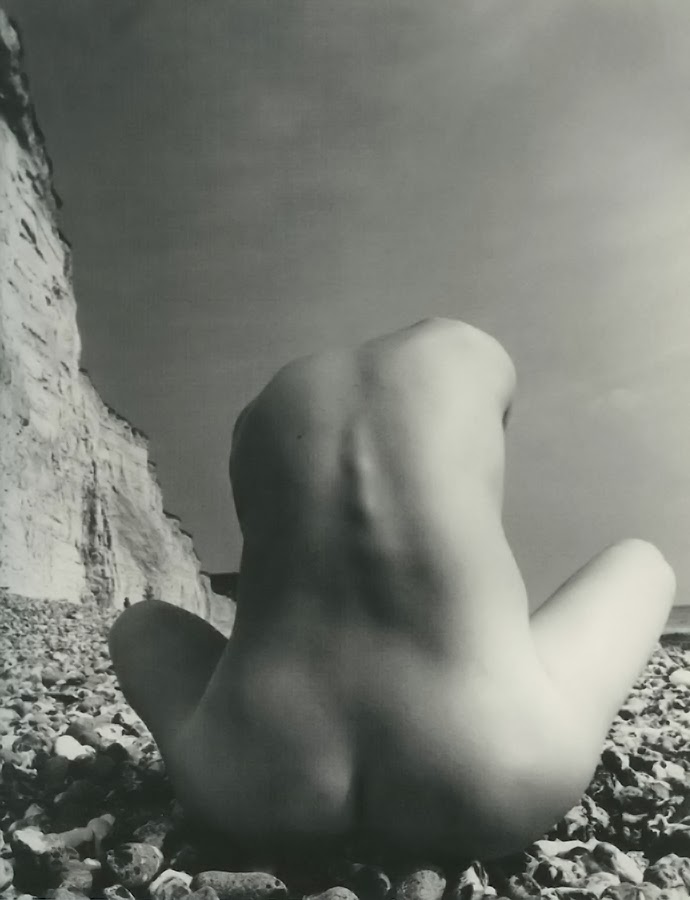

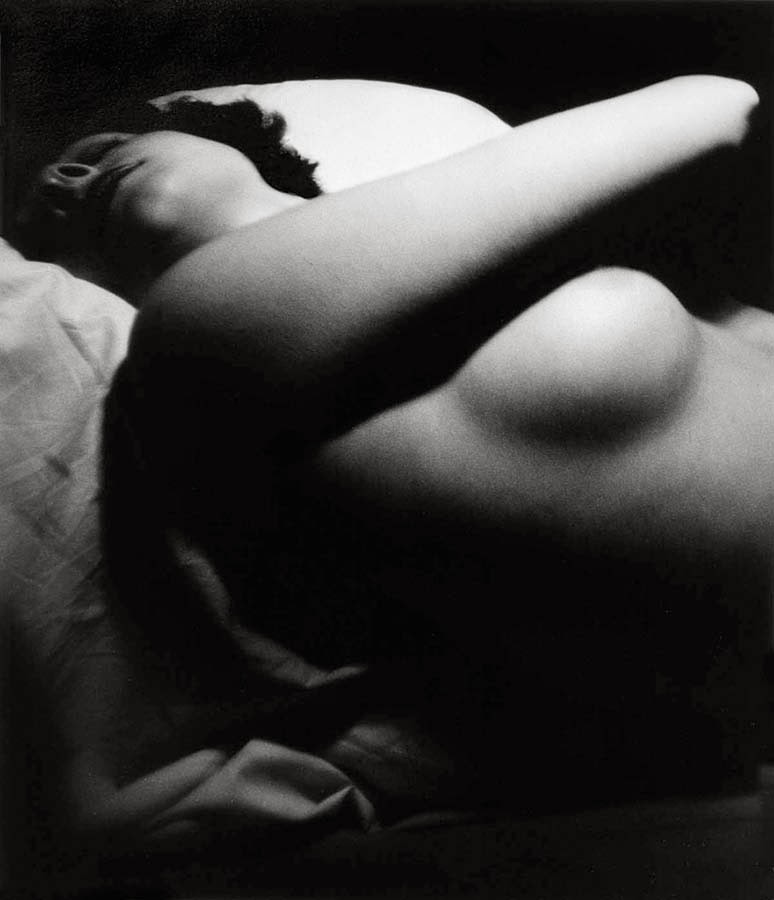

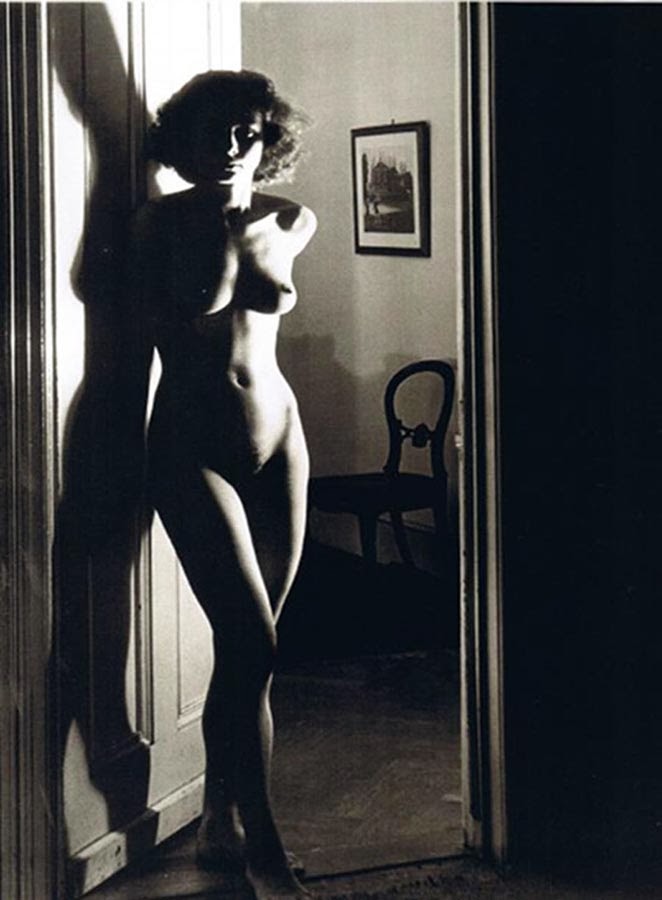

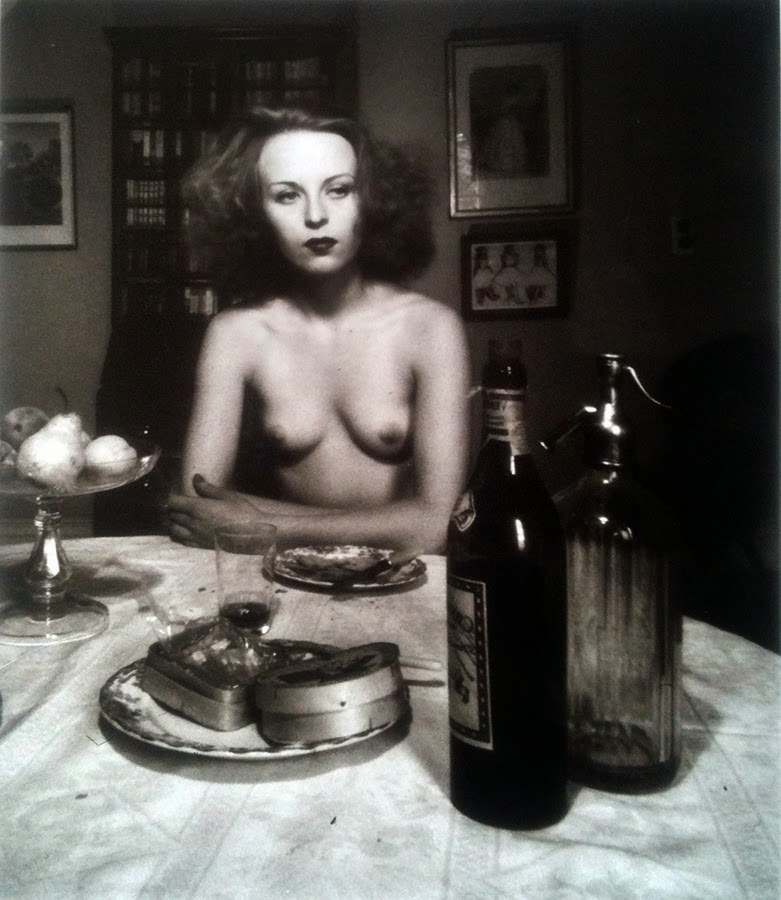

‘Instead of photographing what I saw, I photographed what the camera was seeing. I interfered very little, and the lens produced anatomical images and shapes which my eyes had never observed.’

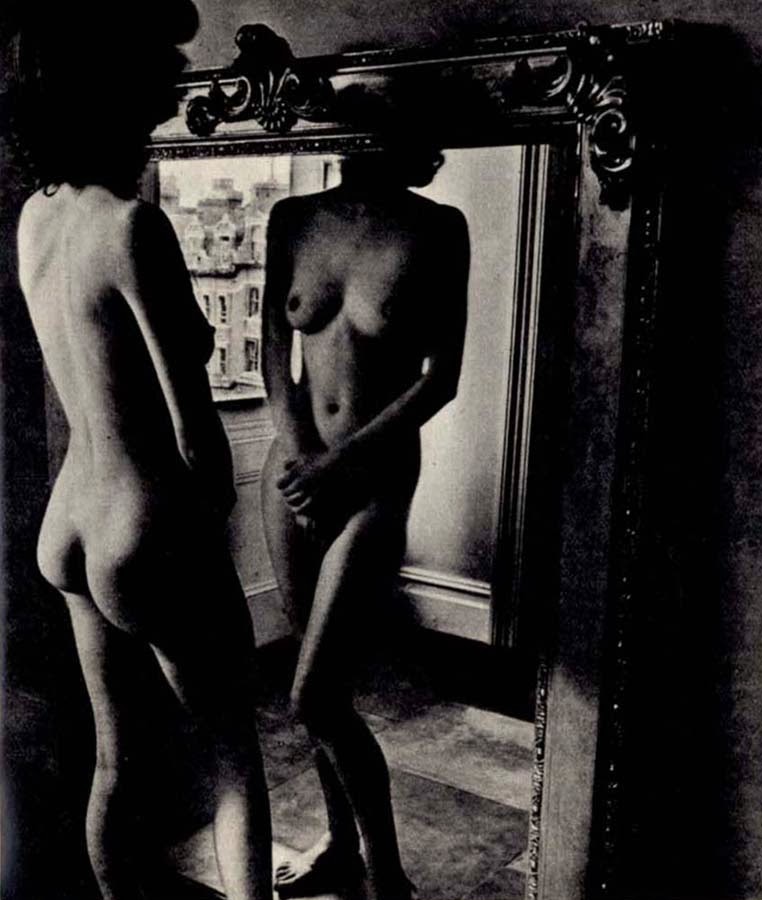

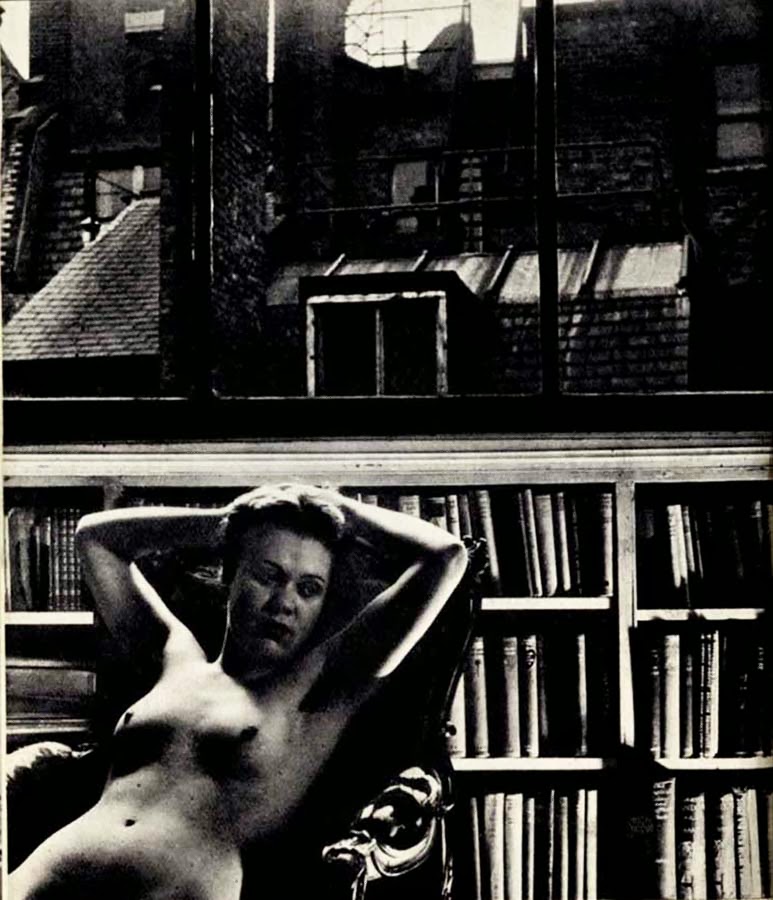

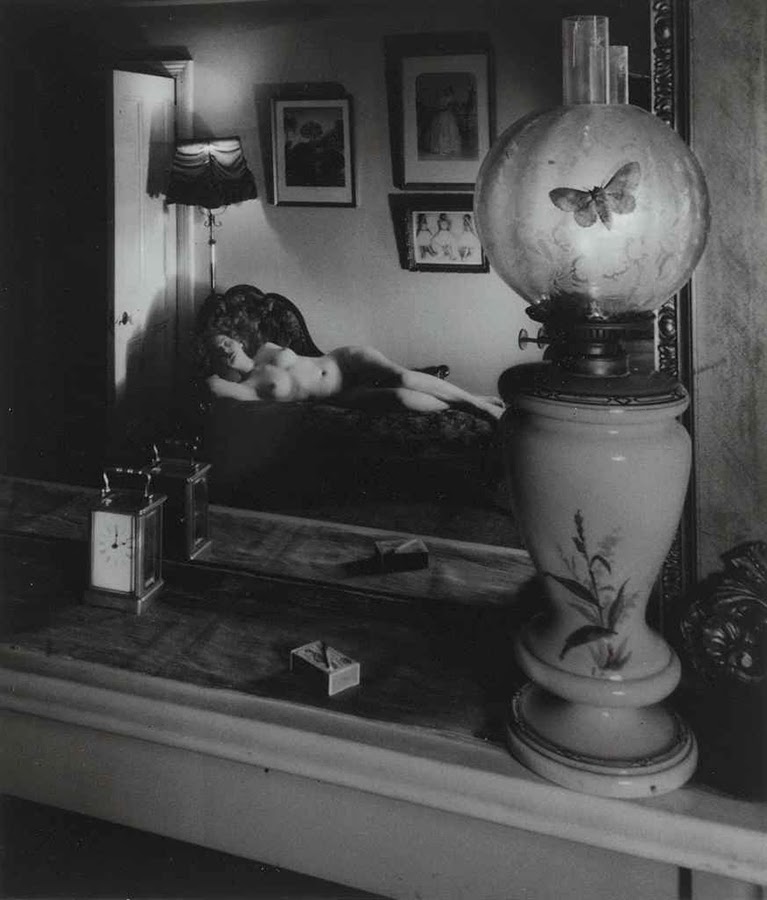

Brandt had experimented with nude photography since the 1930s but made a decisive breakthrough in 1944 when he acquired a 1931 Kodak camera with a wide-angle lens, used by the police for crime scene records. This allowed him to see, he said, “like a mouse, a fish or a fly”. The nudes reveal Brandt’s intimate knowledge of the École de Paris – particularly Man Ray, Picasso, Matisse and Arp, together with his admiration for Henry Moore.

He published Perspective of Nudes in 1961 which featured nudes in domestic interiors and studios, on the beaches of East Sussex and in France. He used a Superwide Hasselblad for the beach photographs. In 1977-78 Brandt added further nudes, published in Nudes, 1945-80. Brandt used professional models but also sometimes family and friends. His second wife, the journalist Marjorie Beckett, modelled for the Campden Hill photograph.

Bill Brandt’s last years were spent reissuing his work in a series of books published by Gordon Fraser. He taught Royal College of Art photography students and continued to accept commissions for portraits. He selected an exhibition for the Victoria and Albert Museum titled The Land: 20th Century Landscape Photographs (1975) and was working on another show, Bill Brandt’s Literary Britain, when he died after a short illness in 1983. The exhibition became a memorial tribute to Brandt the following year.

Available Publications:

The English At Home – Bill Brandt (1936) (Flikr set by Pete Woodhead)

A Night in London (1938) – Bill Brandt (full .pdf)

Comments

Masters of Monochrome: Part VI- Bill Brandt — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>