Part I:

The Clouds, Parted.

Throughout the world, the 1920’s represented a decade of exciting social changes and profound cultural conflicts. That brief period was drastically divided between postwar decadence, an almost unprecedented liberal movement in arts and culture, incredible economic collapse and vicious right-wing conservatism. From the world of fashion to the world to politics, forces clashed to produce the most explosive decade of the century.

In this series of articles and images, I want to review the people,

places and things arising from this brief period which have directly

influenced my own romantic notions of it. Although many of these cultural shifts were practically global, the primary centers were Berlin, Paris and the US cities of New York and Chicago.

As a bit of a disclaimer; many of the personalities, styles and movements that I wish to explore evolved in the decades prior to 1920, and many reached their zenith in the decades after. Many of them are, in fact, still relevant today: history is not always static. In some cases I am using artwork and photography from other periods, but I do so with the intent of illustrating the particular concept as clearly as possible; in all cases the people, ideas, movements and culture depicted had a direct impact on the era.

|

| Battle of Broodseinde, Ernest Brooks 1917 |

|

| “The Night“, Max Beckmann (1918-19) |

The final years of the First World War (July 1914 – November 1918) had left the map of Europe dramatically altered. Over 37 million people, both soldiers and civilians, had died either directly from the conflict or from the ensuing disease and starvation. In the words of historian Samuel Hynes, “…Those who survived were shocked, disillusioned and embittered by their

war experiences, and saw that their real enemies were not the Germans,

but the old men at home who had lied to them. They rejected the values

of the society that had sent them to war, and in doing so separated

their own generation from the past and from their cultural inheritance.”

|

| “My Friends at Cafe du Dome” André Kertész, 1928 |

|

| Disabled war veteran reduced to begging, Berlin 1923 |

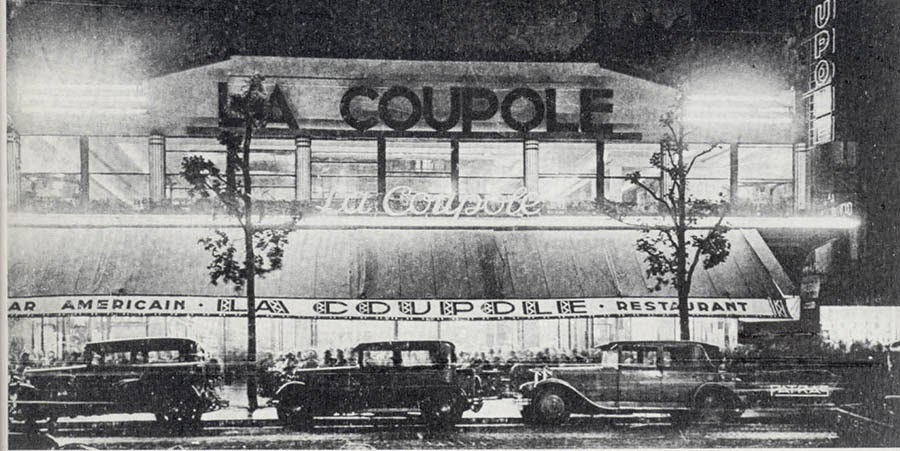

Perhaps more than any previous decade, the 20’s saw the rise of many cross-cultural styles and ideologies. The technological advances in film and radio had an enormous influence on what would later be known as “mass media”, and allowed new trends in music, fashion, arts and philosophy to reach a global audience at unprecedented speeds. In addition, vast numbers of refugees were resettling in both Europe and America, bringing new ideas and concepts with them. From the ashes of conflict there rose a seemingly homogenous blend of the French “Années Folles“, the American “Roaring 20’s” and the German Weimar Republic- a consolidated culture often collectively considered as “Bohemian”.

|

| Women factory workers in Britain, 1916-1918 |

World War had also compounded a gender imbalance; the number of unmarried women seeking means of support, both emotional and economic, grew dramatically. The closure of many of the wartime factories meant that women who had worked during the war now found themselves struggling

to find jobs and those approaching working age were offered few, if any,

legitimate opportunities.

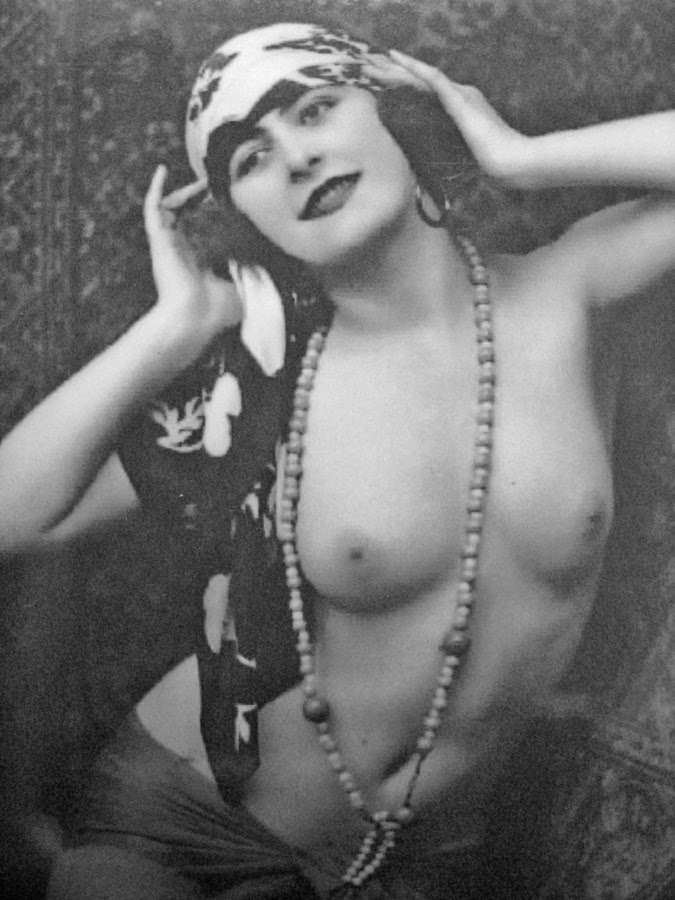

The almost instantly recognized slang term “Flapper” (in France the “garçonne” and “Backfisch” in Germany) can be traced back at least to the end of the 19th century, but by the early 20s it had come to define a generation of young women. In a 1920 lecture on Britain’s surplus of young women Dr. R. Murray-Leslie criticized “the

social butterfly type… the frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing flapper,

irresponsible and undisciplined, to whom a dance, a new hat, or a man

with a car, were of more importance than the fate of nations“.

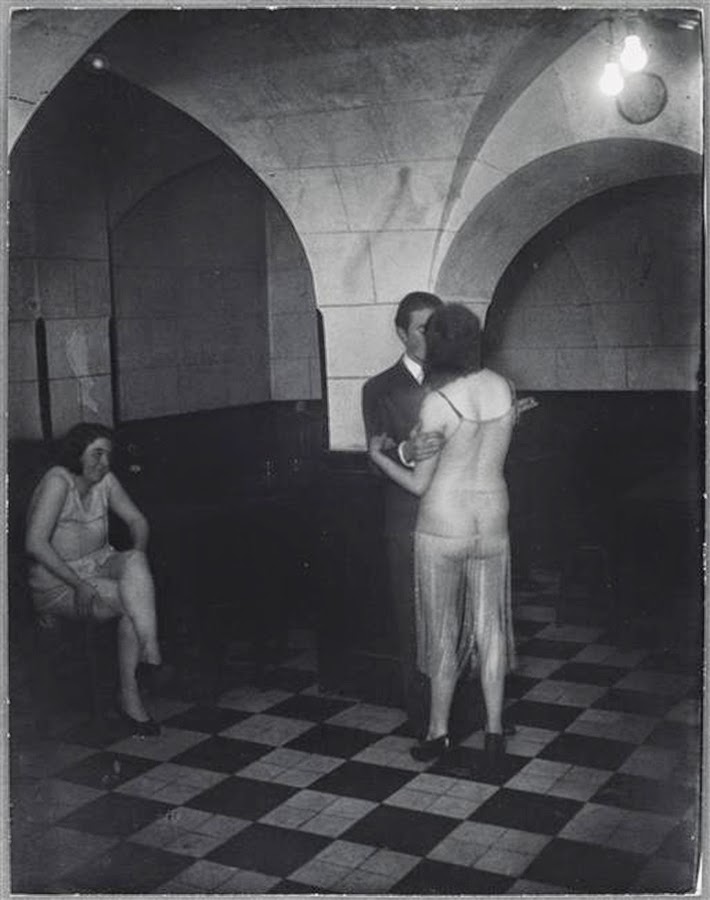

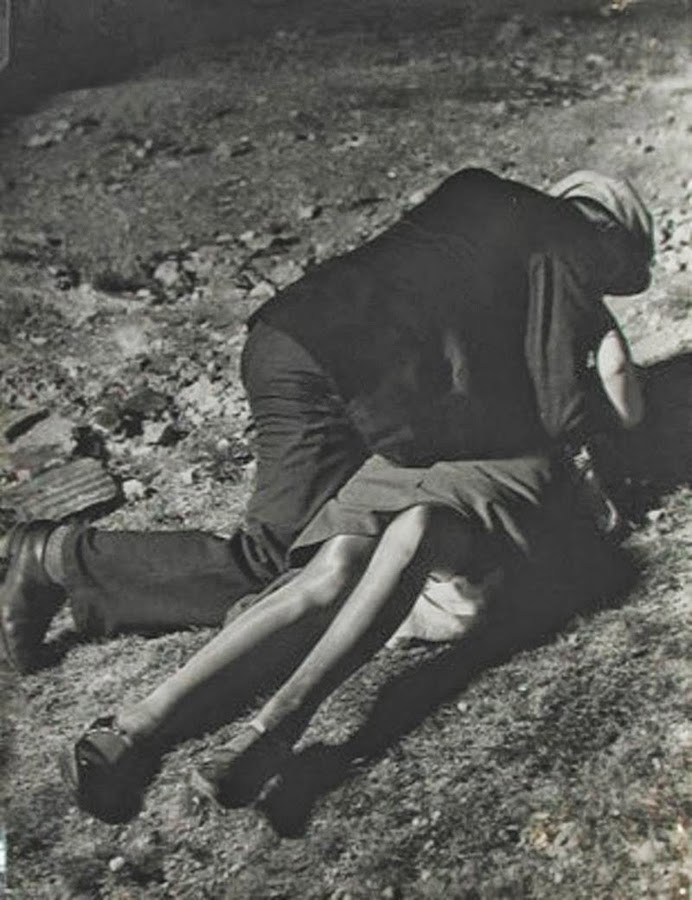

The flappers rejected traditional rules of propriety in favor of a

more modern, fast-paced lifestyle. They were frank, socially liberated,

hedonistic and reckless, often acting in ways that shocked the older generation. Young women began openly smoking and drinking, activities which had previously been limited to

men. They cut their hair into a short “bob” or “shingle” cut, rejected the

waist-constricting corset, and

adopted a more androgynous look. Flappers were particularly known for their style which largely emerged as a result of French fashions, especially those pioneered by Coco Chanel. Loose-fitting

dresses with drop waists and knee-length skirts created a more boyish

silhouette which some women enhanced by binding their breasts.

Flappers

also began to wear makeup, which had previously been associated only

with prostitution. They also changed the way cosmetics were

used; instead of attempting to imitate nature, flappers created a deliberately unnatural appearance using lipstick and powder

to create small bow mouths and ghostly-pale skin.

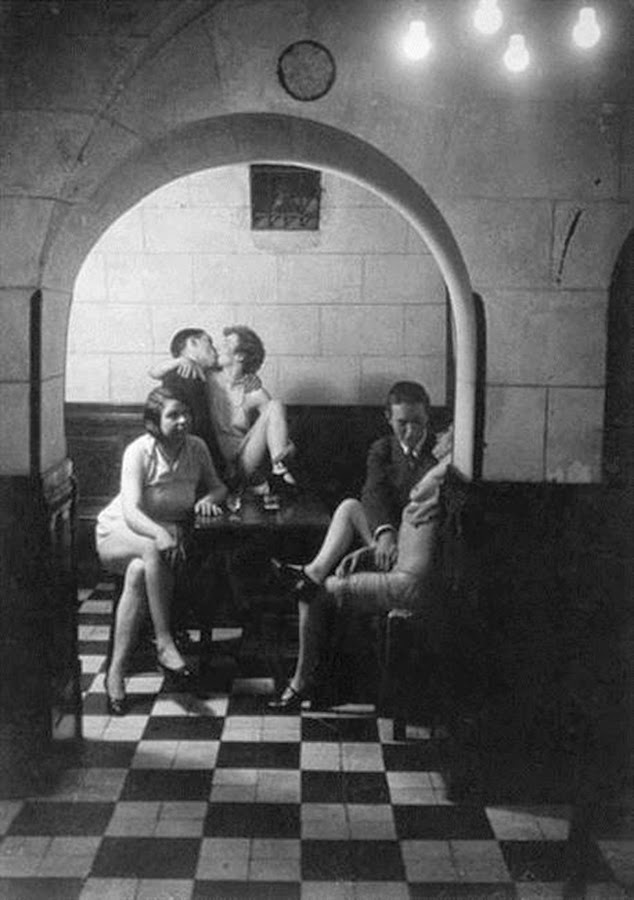

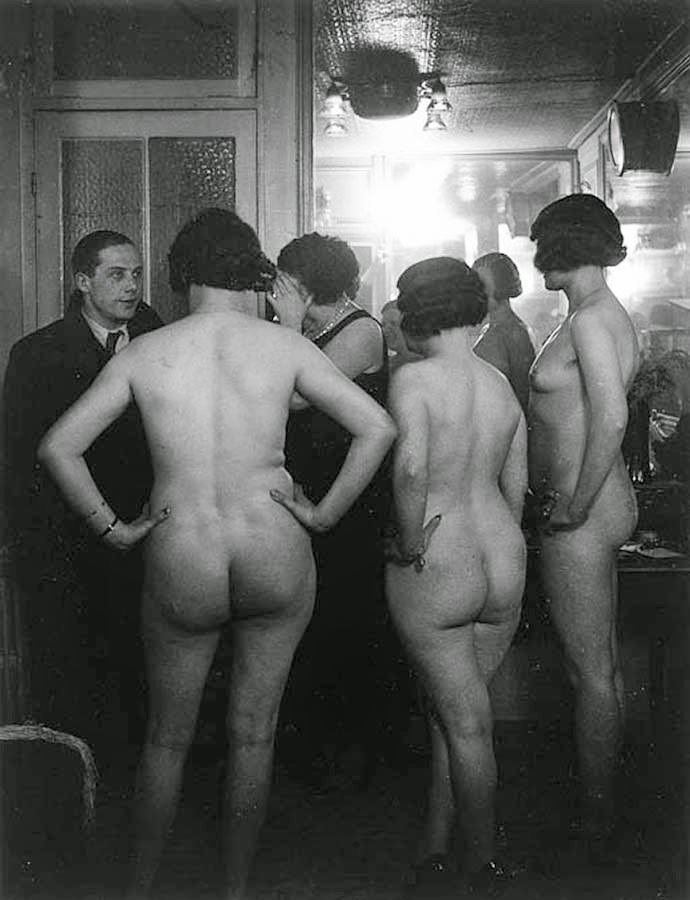

The concept of the “new woman” during the 1920s also carried a strong sexual connotation. Emerging from the Victorian generation which, socially, offered little middle-ground between prostitution and abstinence, the unmarried women stepped out of their traditional gender roles and into an undefined social structure.

The young women of the 1920s were educated about sex and had no qualms about discussing it openly in mixed company; on the fringe of this restructuring of the sexual norms were the prostitutes, radical feminists and lesbians, maintaining a significant

continuity in sexual behavior and thought.

|

| Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann: Grand Salon, 1925 Paris Exhibition |

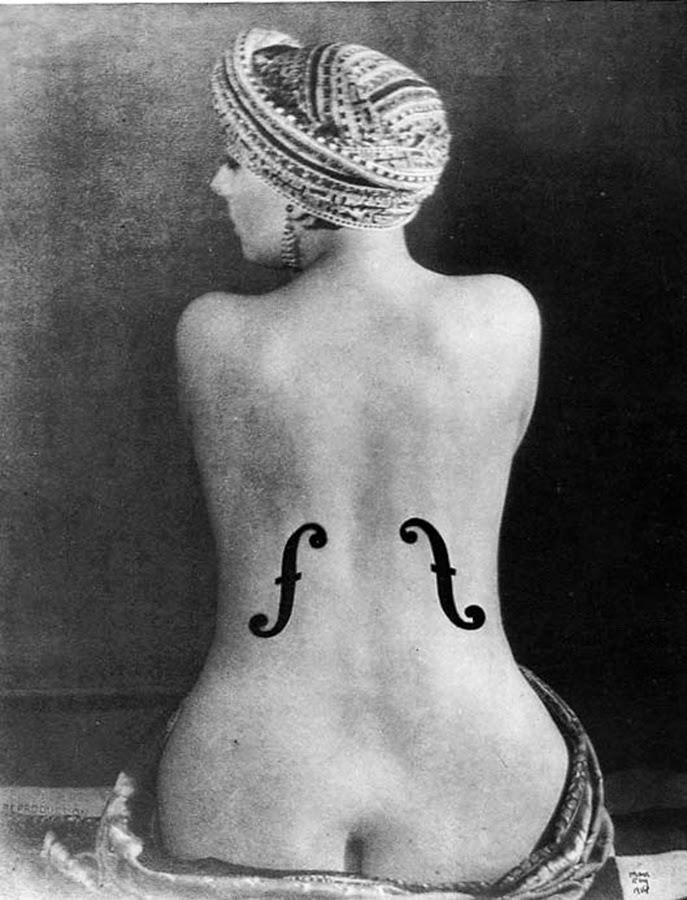

In the world of the arts, those at the forefront of interpreting this new cultural mix responded with innovations born out of the astounding advances in technology brought on by conflict, the deep emotional scars that it had left on society as a whole, and the enthusiastic embrace of liberation. In America the “Harlem Renaissance” exploded out of New York and Chicago, carrying the banner of Jazz music at its forefront. In Berlin the Weimar Republic began experimenting in some of the world’s most advanced politics,science and philosophy, at the same time redefining the social norms of human sexuality. In Paris André Breton was introducing surrealism to the world.

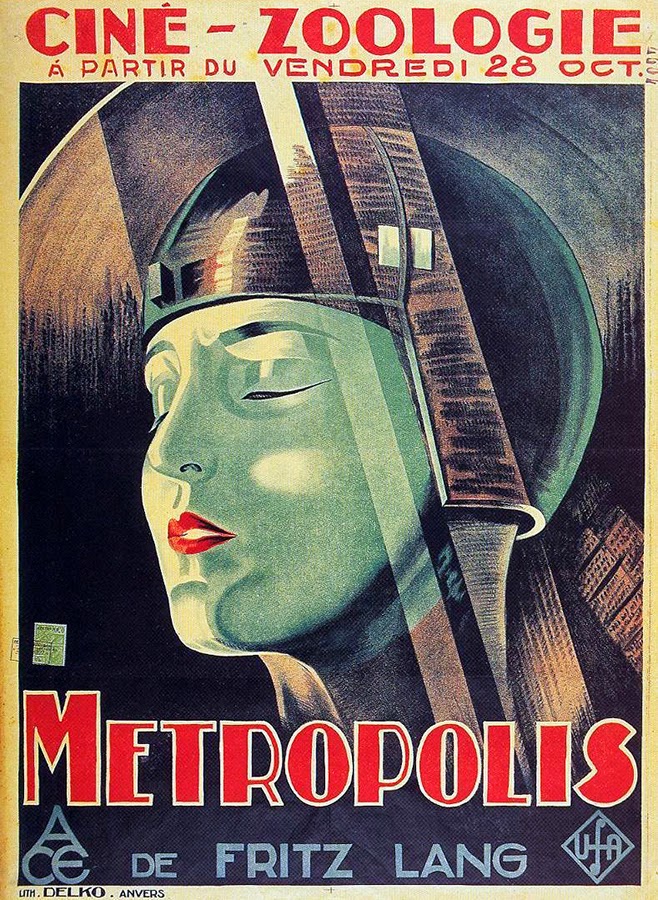

Replacing the more elaborate Art Nouveau styles associated with the previous generation, the new artistic movement of Art Deco flourished throughout the 1920’s. Minimalist and streamlined, the Art Deco style featured boldly defined geometric shapes, hard lines, vibrant coloring and oversize lettering; it was applied broadly to architecture, furniture design, fashion, advertising and many other areas throughout the decade.

Dada in Paris surged in 1920 when many of the originators converged there. Inspired by Tzara, Paris Dada soon issued manifestos, organized demonstrations, staged performances and produced a number of journals. Led by the French writer and poet André Breton, Surrealism had developed out of the Dada movement during the war; also centered in Paris, the movement spread around the globe strongly affecting not only the visual arts, philosophy and literature of many countries but also political thought and social theory.

|

| Back row: Man Ray, Jean Arp, Yves Tanguy and André Breton. Front row: Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dalí, Paul Éluard, Max Ernst and Rene Crevel. (Photo Man Ray, 1930.) |

In Germany the Bauhaus art school was combining crafts and the fine arts, and it soon became famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. Founded upon the idea of creating a “total” work in which all arts, including architecture, would eventually be brought together, the Bauhaus style later became one of the most influential currents in modern design and architecture. The most important influence on Bauhaus was modernism, a cultural movement originating in the 1880s whose design innovations combined radically simplified forms, rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass-production was reconcilable with the individual artistic spirit.

Meanwhile the Devětsil (see previous post “Karel Teige: Пролеткульт and the Devětsil“), an association of Czech avant-garde artists, was born in Prague; and Constructivism, a rejection of the idea of autonomous art in favor of art as a practice for social purposes, was taking hold in Russia.

The 1920s also marked an influential period in the arts of photography and filmmaking. In 1923 Kodak released their first compact 16mm motion picture camera. Two years later the Ernst Leitz Optische Werke in Wetzlar, Germany, released another new type of camera; designed as a way to use surplus 35mm movie film, the new Leica allowed photographers to go practically anywhere and take photos unobtrusively. The Leica’s immediate popularity spawned a number of competitors and

cemented the position of 35 mm as the format of choice for high-end compact cameras. Freed from bulky equipment, the result was a dramatic shift in the arts of both still photography and cinematography: from primarily posed scenes to natural images of people in their daily lives. It was the beginning of modern photojournalism.

In commercial cinema, 1922 saw the release of the first all-color feature, The Toll of the Sea. In 1926 the American Warner Bros. Studio released Don Juan, the first feature film with sound effects and music. It was followed by The Jazz Singer in 1927, the first feature film to include limited talking sequences.

This release arguably launched the “Golden Age of Hollywood”, ending the

silent era. Following the rise of “talkies”, large studios around the world began acquiring movie theater chains. By the 1920s, the American film industry had relocated to Hollywood, drawn by its cheap land and labor, the varied scenery that was readily accessible, and a suitable climate ideal for year-round filming (some filmmakers

moved to avoid lawsuits from individuals like Thomas Edison who owned

patent rights over the filmmaking process). Each year, Hollywood released nearly 700 movies, dominating worldwide film production. By 1926, Hollywood had captured 95 of the British market and 70 percent of the French market.

|

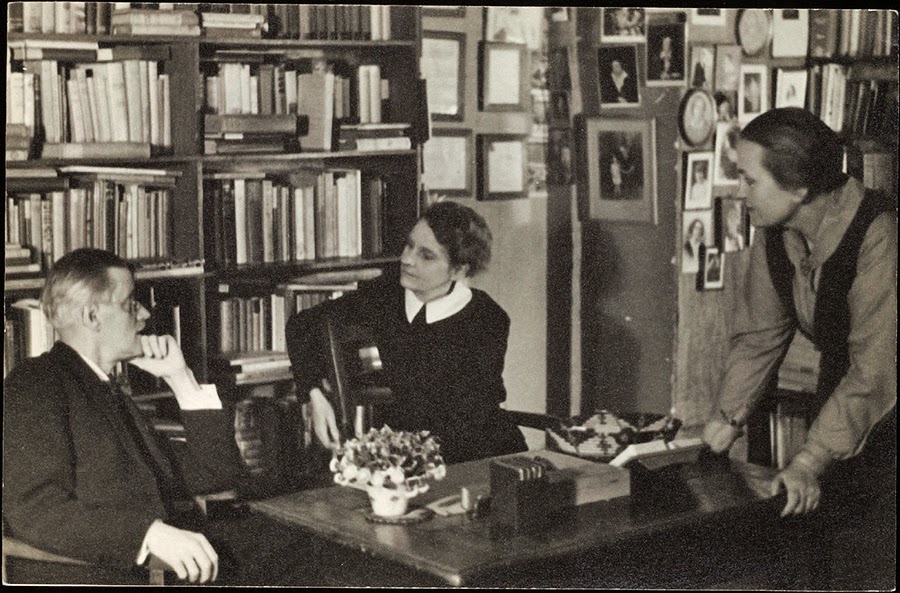

| James Joyce with Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier at Shakespeare & Co., Paris, 1920 |

Literary creatively also soared, with the overly formal

styles associated with pre-war literature being replaced with a more direct, personal style. The disillusionment following World War I caused some writers to focus on the horror and futility of war but other common themes in 1920’s literature focused on sexuality and the human need to seek pleasure.

While living in Paris during the early ’20s, American writer Gertrude Stein was waiting for her car to be serviced and reportedly overheard the angry shop owner shout at a younger mechanic “… You are all a génération perdue“, a lost generation. In recounting the story to Ernest Hemingway, Stein added, “That is what you are. That’s what you all are … all of you

young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation.” In American literature F. Scott Fitzgerald, T.S. Elliot, John Dos Passos and many others embraced the label.

Among the European writers emerging at the time, two

things stand out; the sense of despair, bitterness and anxiety, and the

maturation of the modernist literary movement. Writers like James Joyce,

D. H. Lawrence and Marcel Proust emerged as giants.

|

| Ma Rainey & the Georgia Jazz Band, Chicago Illinois 1923 |

Musically, the period from the end of the First World War until the start of the Depression in 1929 is known even today as the “Jazz Age”. Jazz played a significant part in wider cultural changes during the period, and its influence on pop culture continued long afterwards. Although jazz music had originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in the Southern United States, its fusion of African polyrythms, improv and syncopation with European harmony and forms allowed it to become socially acceptable to white Americans and Europeans.

Radio was a novelty in the early twenties, but by end of the decade it had become a common necessity; a viable broadcast industry and a boom for musicians. By the end of August 1920 the first known radio news program was broadcast by station 8MK in Detroit, Michigan; in 1922 the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) was created and regular wireless broadcasts for entertainment began in the UK from the Marconi Research Center.

During the mid 1920s the advent of amplifying vacuum tubes had revolutionized radio receivers and transmitters; radio soon altered the daily habits of its listeners more than any other previous invention. As television does today, radio provided people a source of entertainment they could share. Radio programs ranged from live theater to sporting events, and from symphony concerts and jazz to broadcasts of important events.

|

| Duke Ellington |

|

| The Cotton Club, late 20s-early 30s |

|

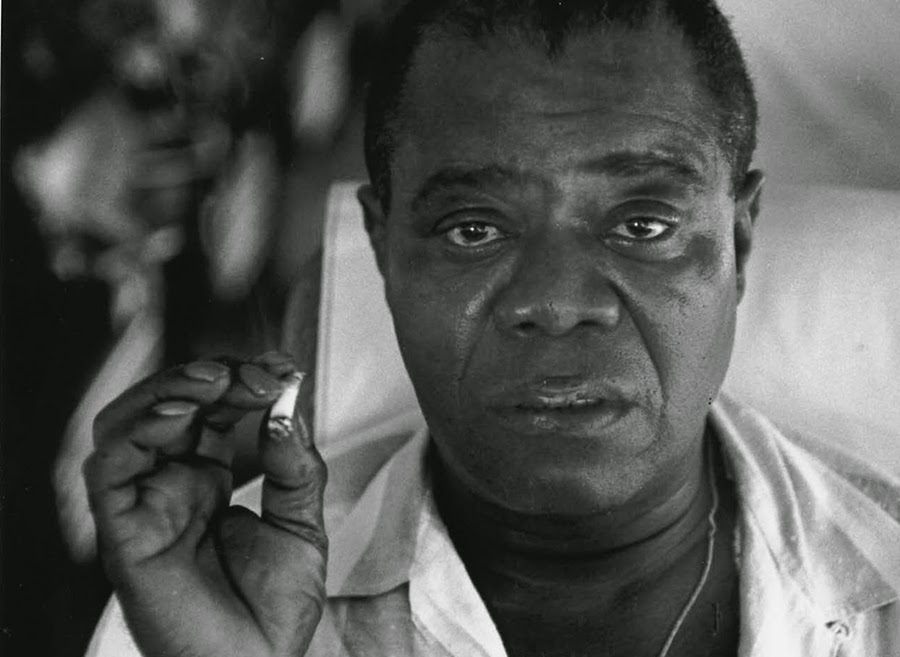

| Louis Armstrong |

|

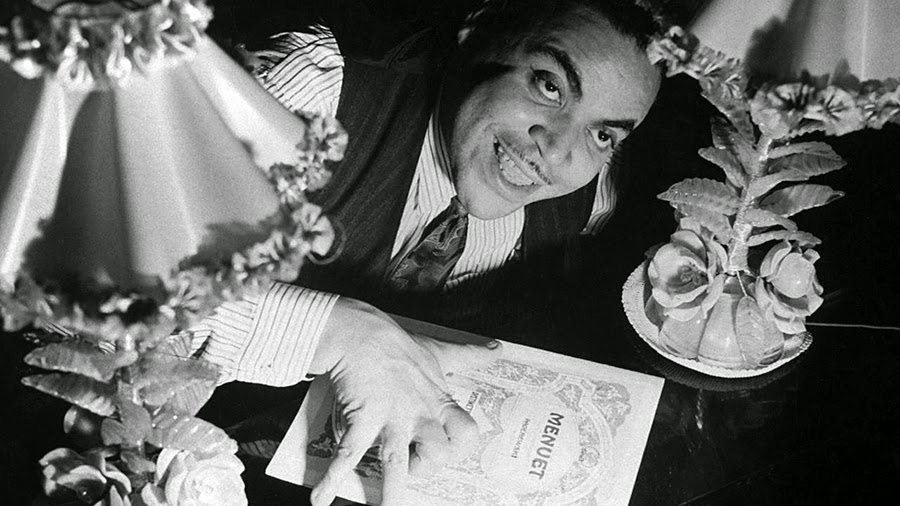

| Thomas “Fats” Waller |

In the next three articles I’ll focus on the individual social, artistic and cultural scenes that blossomed in Paris, America and Berlin during this brief period.