Hadji Dimitar was the leader of a small group of Bulgarian rebels, mortally wounded on July 30, 1868 while fighting the Turks on Buzludzha Peak near Kazanlak.

In 1891, a group of socialists lead by Dimitar Blagoev met on the same peak to plan for Bulgaria’s future, resulting in the birth of the Bulgarian Socialist Party.

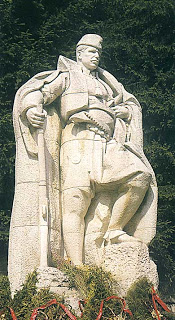

In 1961 a monument was built to commemorate Hadji Dimitar’s act of heroism: a marble figure of Dimiter is outlined against the green background of firs, cedars and pines.

In 1974 construction began on another monument to commemorate Blagoev’s contribution to his country: designed by Georgi Stoilov, it took the equivalent of €14,186,000 ($20,387,292) and seven years to complete.

They didn’t plant any pine trees.

Work on the monument was undertaken by units of the Bulgarian Army, and it consistedof a domed hall and a 70 foot tall pillar topped with an embedded red glass window in the shape of a star. The ceremonial hall is 42 meters in diameter and 14.5 meters high, decorated with 550 square meters of mosaics evoking the struggles of the Bulgarian Workers’ Social Democratic Party and the construction of socialist society. In the balcony around the hall were 14 mosaics reflecting home life.

Layout of the monument took 18 months and involved over 60 artists, including Dimitar Kirov , Velichko Minekov and Valentin Starchev. The three staircases were decorated with combinations of white glass made by the Czech sculptor Stanislav Libenski.

For 8 years, from its opening in 1981 to the collapse of the government in 1990 the Memorial House hosted local party meetings, government functions and even annual youth discos.

After the government’s fall from power in 1989 the site was abandoned and left open to vandalism. All salvageable metal has since been removed by scrappers, and locals -allegedly spurred by rumors that the great red star in the pillar was actually made from rubies- shot it out. Their hopes for riches crumbled with the broken glass.

Even though almost all of the artwork has been removed or destroyed, the concrete structure still stands against the elements. There are no plans to renovate the building or surrounding area. Today it is popularly known as the “Kazanlak UFO”.

“Aloysha” Monument to the Red Army; Granite, Kotsev, Topalov and Zankov, 1957: Plovdiv

Generally believed to be named after Alexei Skurlatov, a 22-year old Russian signaler who was among the first Soviet soldiers to enter Bulgaria in 1944, Alyosha stands vigil at the peak of the 300 meter Bunarjik hill in Plovdiv.

Begun in 1954 and officially opened three years later, the 10.5 meter (34 foot) granite statue was created by Bulgarian sculptures Radoslavov Kotsev, Topalov and Zankov. Around the base of the monument is a platform with a panoramic view of Plovdiv and the Rhodope Mountains.

“When one of my father’s friends saw the monument 13 years later, he said, ”Alyosha! Brother!“ and wrote his name on the statue with chalk . Since then people have called it Alyosha,” explained Alexei Skurlatov’s daughter.

The monument has not been without controversy: after the collapse of the Soviet Union it was smeared with black paint and on one occasion hundreds gathered at the foot of the hill calling for it to be torn down. In the early 1990s the mayor of Plovdiv wanted to dynamite the monument, but as it would be necessary to evacuate a third of the city’s population the idea was rejected: as an alternative he attempted to have it covered with a gigantic Coca-Cola can, probably with some schemes of advertising profits.

Yet to many Alyosha still seems to convey a message:

“He turns to the East, with his back to those he fought against during WW2. He’s a symbol of peace. His gun faces downwards – he doesn’t want war,” according to one Plovdiv Regional Governor.

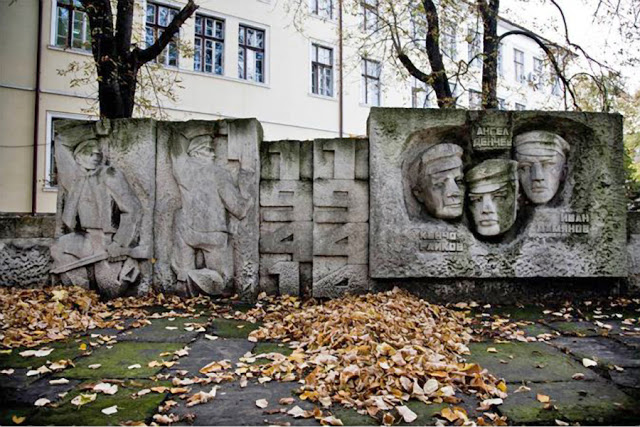

Monument to Bulgarian-Soviet Relations; Concrete, Kamen Goranov, 1978: Varna

Built on Turna Tepe hill, where the Russian forces launched their successful attack on Varna during the Russian-Turkish War of 1828, the monument to the Bulgarian-Soviet friendship was constructed over a period of 7 months with the help of 27,000 volunteers. It comprises some 10,000 tons of concrete and app. 1,000 tons of steel.

Today the eternal flame has disappeared, and the original massive bronze letters of an inscription reading “Friendship for centuries throughout centuries” has been pried from the walls by metal thieves and most likely sold for scrap. The internal chamber of the monument which once housed local Communist party gatherings was recently being used as storage for old tires.

Founders of the Bulgarian State Memorial Complex; Concrete, Georgi Geshev, Blagoi Atanasov, 1981: Shumen

On the Ilchov Hill just outside of Shumen, the monument is dramatically visible within a radius of 30 kilometers (18 miles). A masterpiece of cubist art by a team of sculptors (Krum Damyanov and Ivan Slavov), architects (Georgi Gechev and Blagoi Atanasov), artists (Vlasislav Paskalev and Simeon Venov) and the engineer Preslav Hadjov, it stands 52 meters (170 feet) high at its peak.

The monument has little to do with Socialist propaganda (other than being funded with Rubles) instead focusing on the foundations of Bulgarian culture: built in honor of the anniversary of the establishment of the Bulgarian state, it depicts key moments in the history of the First Bulgarian Empire.

The architectural space consists of 8 units set at angles of 45°, 60° and 90° which result in the formation of two semi-halls resembling a spiral, a historical symbol of prosperity. The figure of a lion created from 2,000 individual granite slabs with a combined weight of 1,000 tons crowns the monument: behind its tail a stylized butterfly suggests the association with the metamorphoses in Bulgarian history.

The complex interior hosts statues of the Bulgarian Tsars Asparukh, Tervel, Krum, Omurtag, Boris I and Simeon I as well as the largest triptych mosaic in Europe.

The mosaic includes two elements; figures depicting rulers, men of letters, boyars and warriors are combined with type in runic letters, Glagolitic alphabet and Cyrillic alphabet.

In the first panel, “The Victors” warriors acclaim the Khan dressed in crimson; the second panel depicts the acceptance of Christianity and a third represents the brothers Cyril and Methodius with their disciples.

Defenders of Stara Zagora Memorial Complex; Concrete, Boris Davidkov, Blagoi Valkov, 1977: Stara Zagora

In the April Uprising of 1876, ethnic Bulgarians began a bloody rebellion against the Ottoman Empire sparking horrendous massacres by detachments of regular and irregular Ottoman troops (bashi-bazouks). The insurrection was suppressed within a month, and Eugene Schuyler -an American scholar, explorer and diplomat- reported after arriving in Bulgaria two months later an estimated 15,000 civilians were murdered. From Batak he wrote:

“…On every side were human bones, skulls, ribs, and even complete skeletons, heads of girls still adorned with braids of long hair, bones of children, skeletons still encased in clothing. Here was a house the floor of which was white with the ashes and charred bones of thirty persons burned alive there. Here was the spot where the village notable Trandafil was spitted on a pike and then roasted, and where he is now buried; there was a foul hole full of decomposing bodies; here a mill dam filled with swollen corpses; here the school house, where 200 women and children had taken refuge there were burned alive, and here the church and churchyard, where fully a thousand half-decayed forms were still to be seen, filling the enclosure in a heap several feet high, arms, feet, and heads protruding from the stones which had vainly been thrown there to hide them, and poisoning all the air…Since my visit, by orders of the Mutessarif, the Kaimakam of Tatar Bazardjik was sent to Batak, with some lime to aid in the decomposition of the bodies, and to prevent a pestilence…Ahmed Aga, who commanded at the massacre, has been decorated and promoted to the rank of Yuz-bashi…”

When the details became known in Europe the strongest reaction came from Russia, who declared war on the Ottomans on 24 April 1877. On July 31 of the same year a Turkish battalion of several thousand soldiers attacked the town of Stara Zagora, which was defended only by a small Russian detachment and Bulgarian volunteers.

The Russian troops fought under 5 flags which they had brought from their homeland; the last banner to fall was the flag of Samara, which was reportedly snatched from the grasp of a dying carrier by Lieutenant-Colonel P. P. Kalitin and carried forward until he himself was brought down by Turkish rifles. After a fierce 6 hour battle the remnants of the defenders were forced to surrender, the city was razed and an estimated 14,500 Bulgarians were massacred.

Eventually the Russians and their allies emerged victorious, with Russia accepting a truce offered by the Ottoman Empire on January 31, 1878. After almost five centuries of Ottoman domination (1396–1878), the Bulgarian state was reestablished as the Principality of Bulgaria, covering the land between the Danube River and the Balkan Mountains.

In 1977, one hundred years after these memorable events, the Memorial Complex was inaugurated on the same location as the defenders’ command post. The 50-meter (164 foot) tall concrete structure was designed to resemble the banner of Samara, with a window representing the cross and a ceramic mosaic in black, dark green and gold.

An ossuary was built into the foundation, and bronze statues of six Bulgarian volunteers and a Russian officer keep eternal watch from an adjacent rampart.

1300 Years Monument; Marble, Alexander Barov, Atanas Agura, Vladimir Romenski, 1981: Sofia

Slowly rotting behind a graffiti covered construction fence in Yuzhen Park in the center of Bulgaria’s capital city Sofia, the monument was built to commemorate the 1,300th anniversary of the foundation of the Bulgarian State, part of a major nationwide building program to celebrate the event. Poor planning forced the architects and designers to rush the construction in order to meet the required date, and the monument was completed in only 8 months.

Almost immediately after the inauguration the monument began to collapse: the steel is poor quality, tiles were smaller than the ones specified and the joints were never properly sealed. After the collapse of the government in the early ’90s maintenance of the memorial was completely abandoned by the authorities.

As the heavy tiles continued to peel away from the structure it became a public hazard; in preparation for a visit by Pope John Paul II in 2002 a steel security fence was erected, practically the only improvement implemented in the two decades since its construction despite -or possibly due to- long standing political disagreements on the merits of demolition vs. restoration. Ironically the fence has become something of an attraction in itself, serving as a canvas for the numerous graffiti artists in the area.

Intended as a centerpiece of the capital only 20 some years ago, today Lonely Planet lists the 1300 Years Monument as the 40th most important thing to see in Sofia -after “Kokolandia” playground and the Maleeva tennis courts. The monument itself is now hidden behind gigantic commercial billboards, perhaps with the hope that it will someday disappear on its own.

Conceived by the Bulgarian Communist Party Council of Ministers in 1949 to symbolize “the gratitude of the Bulgarian people to the Russian soldiers”, construction for the landmark monument in downtown Sofia began on July 5, 1952: the 1954 opening was attended by Soviet Marshal Sergei Biryuzov.

Conceived by the Bulgarian Communist Party Council of Ministers in 1949 to symbolize “the gratitude of the Bulgarian people to the Russian soldiers”, construction for the landmark monument in downtown Sofia began on July 5, 1952: the 1954 opening was attended by Soviet Marshal Sergei Biryuzov.

The 37 meter tall central monument was designed by a team led by sculptor Ivan Funev and depicts a soldier of the Soviet army surrounded by male and female workers. The pedestal is surrounded with bronze bas-reliefs; the inscription, “the Soviet Army, liberator of grateful Bulgarian people” was originally installed using massive brass letters but these were stolen for scrap sometime in the 1990’s (funding was later raised to carve the inscription into the granite itself). The entrance of the complex is framed with two sculptures and paved with granite, surrounded by large bronze oak wreaths.

Although the monument is maintained by the municipality, it is a traditional gathering place for young people (a large skateboard ramp is located adjacent to it) and perhaps naturally subject to continuous vandalism. Traditionally the graffiti has consisted of various anti-Soviet themes with no particular complexity or depth; however on June 17, 2011 the relief on the western side of the monument was crudely painted to depict heroes of American comic books: Superman, Joker, Captain America and others -along with Ronald McDonald and Santa Claus. The flag was painted with American stars and stripes and the inscription “In keeping with the times” was scrawled below.

Picked up by the media, this particular event quickly went viral and stirred an -until recently dormant- hornets nest both in Sofia and internationally: several anti-communism groups wishing the monument to be demolished were roused along with their conservationist counterparts, and an old debate over which parts of history should be relegated to the past was reignited. Along with this came the usual art vs. vandalism debates, a dialogue on free speech, and heavy condemnation from Russian itself. On “Facebook” over 1700 people (at 19:30 the following Monday evening) were against cleaning the monument. Prosecutors nonetheless initiated an investigation for hooliganism against an unknown perpetrator, while the municipality reported that it found “a cheap company” to clean up the graffiti: which in fact was done by volunteer activists of a Russian organization.

Today more than one hundred monuments built between 1945 and 1989 remain standing in Bulgaria, most of them unrecognized by the government and essentially ownerless. In most cases it is difficult to find information about their designers and history. Once a symbol of pride, most of these communist era monuments are neglected and ransacked due to lack of funding and a general apathy. To quote from the photo essay by Nikola Mihov:

“Regardless of whether they were built to commemorate the Soviet Army or the struggle against Ottoman rule, they all share one and the same fate: to be a silent symbol of the forgotten past.”

A further issue is founded in Bulgaria’s uncomfortable relationship with its past: as mentioned in a recent article on the Soviet Army Memorial in Sofia, “why should one keep monuments that were erected by a political regime, which committed crimes against its own people and/or was subservient to a foreign oppressor? Who erects and keeps monuments of their occupiers?”

Yet many of these pieces are artistic triumphs in their own right. Demolishing them to make room for new fast food joints, parking lots and strip malls in a country with some of the highest poverty rates in Europe seems to simply be trading the icons of one foreign oppressor for another. The “hooligans” who painted the Sofia monument certainly presented a very valid point.

Today I read an article which mentioned a new trend, “Communist Tourism”: Romania is reportedly working on a “red circuit” tour to include traces of the communist dictatorship in the country and highlight places strongly associated with its communist past.

So who knows what the future holds for these decaying symbols…

References:

Communist Political Monuments in Bulgaria

Forget Your Past – Communist Era Monuments in Bulgaria, 2009 – 2011

The Challenges of Abandoned Architecture : Buzludzha Monument / Gueorguy Stoilov

The Soviet Army Monument in Sofia: Keep It but Explain It! -Novinite news, January 27, 2011