Thomas Hart Benton (April 15, 1889 – January 19, 1975) was born in Neosho, Missouri, into an influential family of politicians and powerbrokers. As a result of his father’s political career, Benton spent his childhood shuttling between Washington D.C.

and Missouri, but he rebelled against his grooming for a future political career and decided to

develop his interest in art. As a teenager, he worked as a cartoonist

for the Joplin American newspaper.

In 1907 Benton enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, but left for Paris in 1909 to continue his education at the Académie Julian. In Paris Benton met Diego Rivera and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, an advocate of Synchromism; a movement based on the idea that color and sound are similar phenomena and that the colors in a painting can be orchestrated in the same harmonious way that a composer arranges notes in a symphony.

|

| Field Workers |

|

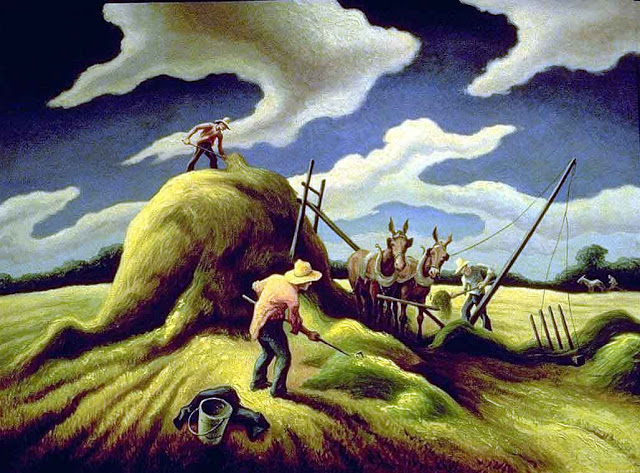

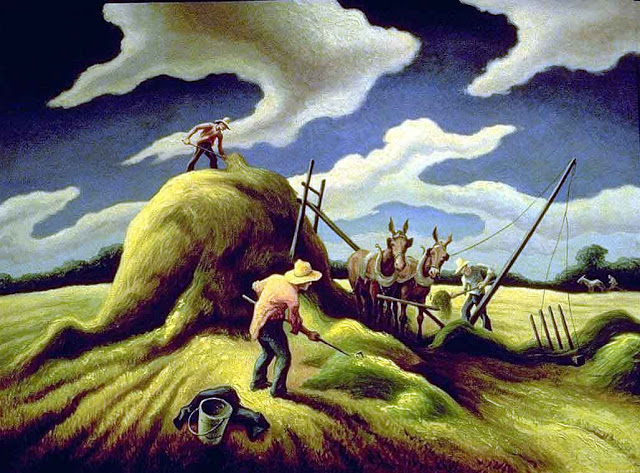

| Haying |

|

| Cut the Line |

Benton moved to New York City in 1913 and resumed painting. During World War I he served in the U.S. Navy as a camoufleur, drawing camouflaged ships that came into Norfolk harbor to ensure that U.S. ship painters were correctly applying the camouflage schemes, aid in identifying U.S. ships that might later be lost and to record the ship camouflage of other Allied navies. He also made drawings and illustrations of shipyard work and life; the requirement for realistic documentation strongly affected his later style.

|

| Boom Town |

|

| Engineer’s Dream |

|

| In the Ozarks |

|

| Life in the City |

In his personal work, Benton declared himself an “enemy of modernism” and began the naturalistic and representational work today known as Regionalism; an academic realism depicting American urban and rural scenes. Benton was active in leftist politics and strongly influenced by the works of the Spanish artist El Greco. He expanded the scale of his Regionalist works, culminating in his America Today murals at the New School for Social Research in 1930-31. These now hang in the lobby of the AXA building at 1290 Sixth Avenue in New York City.

|

| Weighing Cotton |

|

| Strike, Fall River |

During the Great Depression Benton broke through to the mainstream: in 1932 he won a commission to paint the murals of Indiana life that were the state’s contribution to the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago, Illinois. The Indiana Murals stirred controversy; he painted everyday people but he included a portrayal of the state’s history that included some aspects which people did not want publicized, such as Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members in full regalia. On December 24, 1934, Benton was featured on one of the earliest color covers of Time magazine

|

| Over the Mountain |

|

| Palisades |

|

| People of Chilmark |

|

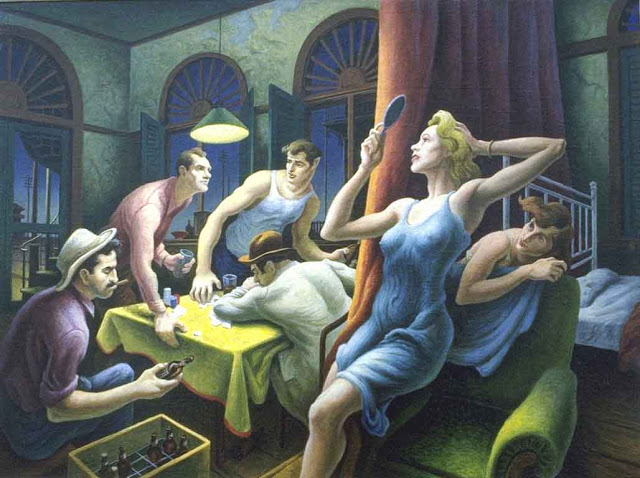

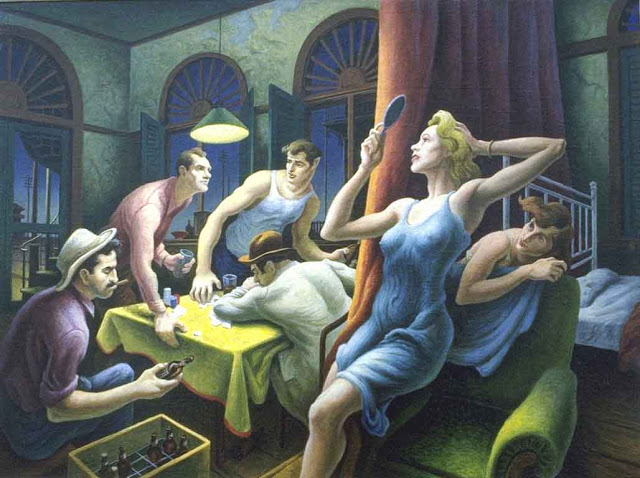

| Poker Night |

In 1935, after “alienating” both the left-leaning community of artists with his disregard for politics -and the larger New York-Paris art world with what was considered a “folksy” style- Benton left the artistic debates of New York for Missouri where he was commissioned to create a mural for the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City. A Social History of Missouri is perhaps Benton’s greatest work: as with his earlier murals, there was controversy over his portrayal of history: he included subjects of slavery, the Missouri outlaw Jesse James and political boss Tom Pendergast. But with his return to Missouri, Benton fully embraced the Regionalist art movement. He settled in Kansas City and accepted a teaching job at the Kansas City Art Institute:

Kansas City afforded Benton greater access to rural America, which was

changing rapidly. His sympathy was with the working class and the

small farmers unable to gain material advantage despite the Industrial Revolution, and often show the melancholy, desperation and beauty of small-town life. Benton was dismissed from the Art Institute in 1941 after he called the typical art museum,

“a graveyard run by a pretty boy with delicate wrists and a swing in

his gait;” and made further references to the excessive influence of homosexuals in the art world.

|

| Life in the West |

|

| Missouri State Capitol |

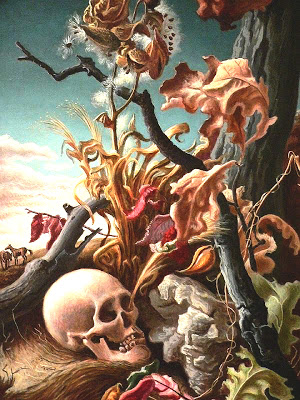

After Many Days Persephone

Susanna and the Elders Retribution

During World War II Benton created a widely distributed series titled The Year of Peril,

which portrayed the threat to American ideals by fascism and Nazism.

Following the war Regionalism fell

from favor, eclipsed by the rise of Abstract Expressionism:

Benton remained active for another 30 years, but his work portrayed

less social commentary and focused more on bucolic images of pre-industrial

farmlands. Benton died in 1975 at work in his studio, just as he completed his final mural, The Sources of Country Music, for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Tennessee.

|

| Back Him Up- Buy War Bonds |

|

| The Source of Country Music |

Comments

Thomas Hart Benton- The Iconography of America — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>